Asking the wrong questions, ignoring the right answers.

Comprehensive Future’s response to the 2016 Green Paper ‘Schools that Work for Everyone’.

“What a strange system it is which kicks children in the teeth at the age of ten at the very time we should be building their confidence and starting to prepare them for the dynamic world in which we live.”

“Dissecting the results from the 2016 PISA study, Andreas Schleicher, director of education for the OECD, said the Pisa data showed ‘clearly and consistently’ that selection by ability at a young age led to middle class students doing better at the expense of the more disadvantaged.”

“The way to improve school quality is not further to divide children and entire areas using unreliable methods of assessment of so-called ability but to invest in high quality comprehensive education.”

“Rarely has a government proposal met with such forceful and largely united opposition within the educational world.”

Comprehensive Future is a non-party organisation committed to phasing out all selective tests as a way of determining entry to secondary schools and supports the establishment of a high quality, inclusive comprehensive system. Our response below is only to that section of the green paper relating to proposed expansion of selective education, which we strongly oppose.

The most striking feature of this consultation is the skewed manner in which it poses its questions. At no point does the government enquire whether respondents agree with its (apparently hastily drawn up) plans to reverse decades of accepted policy and practice on selection. Instead, it simply assumes that the public and profession will agree with its fundamental premise and are thus only asked to offer support and furnish further ideas in order to implement these.

Not only do we reject, then, the very terms on which the questions in this consultation are posed but we note the thin evidence base used by the government in the green paper and the highly partial way it presents its arguments. In the section on selection the government appears to cite a number of different sources (see footnotes 9, 10, 11 and 13) but, in fact, these references can all be traced back to a single study published by the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring in 2008. As Local, Equal, Excellent, an affiliate of Comprehensive Future, points out in its response to the consultation, it is also a pity that the government “sought to rely so heavily on a report by CEM, which is an organisation that makes more than £1 million each year from providing 11-plus test papers, and is therefore not impartial.“

It is also striking what the consultation does not include or make reference to, including numerous studies over the past decade on the negative impact of selection, and the clamour of professional and political opposition to its proposed reforms from senior academics, influential think tanks, former ministers, head teachers, teachers’ unions and its own Chief Inspector of Schools, Sir Michael Wilshaw. Contentious, unproven statements are allowed to stand such as “Many selective schools are employing much smarter tests that seek to see past coaching and assess the true potential of every child” when current evidence suggests that revised versions of the 11-plus exam are anything but ‘smarter’ in that they have made existing discrimination against children from lower income families worse not better.

In contrast, we have drawn from a wide range of recent sources in compiling our response to this section of the consultation.

Q: How should we best support existing grammars to expand?

We shouldn’t.

Comprehensive Future opposes the further expansion of grammar schools as the evidence consistently shows that selective education depresses the educational expectations and attainment of the majority of students and creates damaging and long lasting social and ethnic divides.

There are currently 163 grammars in England which are permitted by law to continue to select by ability. The 1998 School Standards and Framework Act prohibits the establishment of any more selective schools and Comprehensive Future has consistently opposed the expansion, whether overtly or covertly, of any grammar schools. In the past, this growth has been incremental, with many grammar schools increasing their Planned Admission Numbers (PAN) as a way to get round existing legislation. Overall, the number of places in grammar schools increased from 129,000 in 1997 to 167,000 in 2016, and in some areas this unofficial expansion has led to strained relations with surrounding non-selective schools.

Last year, Comprehensive Future sought legal advice regarding a possible judicial review as part of our opposition to the government’s decision to allow the opening of the so-called ‘Sevenoaks Annex’, a proposed extension to the Weald of Kent girls grammar school which is situated approximately ten miles, by road, from the proposed annex. Lack of government openness about the plan, which we described at the time as “a concerted and blatantly political attempt to get round the law”, made it impossible for us to make public the technical grounds of our opposition to this impracticable scheme although we note that the Information Commissioner’s Office has just declared that the original plans for the annex should now be made public.

In this green paper the government has announced its intention to encourage the widespread expansion of selective education, although it is not yet clear by what means this expansion will occur.

Comprehensive Future believes this is not just a backward-looking step but runs counter to the very interests of those children, chiefly those from families on low incomes, that the government claims it wants to help.

The evidence on the harmful effects of academic selection are clear.

According to the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) grammar schools are more likely to benefit wealthy families without raising overall standards. Speaking in September 2016, when presenting the OECD’s annual report comparing education systems across the industrialised world, Andreas Schleicher, director of the OECD, affirmed that “there was no relationship between increasing selection and how well school systems performed….what happens in most European systems is that academic selection becomes social selection.” Countries such as Germany and Switzerland, where selection is widely used, are not more likely to produce high-achieving students. Mr Schleicher added that the “importance of grammar schools is dramatically overplayed. (Instead) there should be more investment for more schools that are more demanding and more rigorous.”

Dissecting the results from the 2016 PISA study, Andreas Schleicher once again stressed that the data showed “clearly and consistently” that “selection by ability at a young age led to middle class students doing better at the expense of the more disadvantaged.”

The OECD’s findings are confirmed by evidence from England. In 2013, in a detailed analysis of the fully selective counties, Chris Cook of the Financial Times found that “introducing selection is not good at raising productivity”, that “poor children are less likely to score very highly at GCSE in grammar areas” and that the “net effect of grammar schools is to disadvantage poor children and help the rich.”

An Education Policy Institute report published in September 2016 concluded that there is “no overall attainment impact of grammar schools, either positive or negative”. The EPI report also found that pupils who are eligible for free school meals are under-represented in grammar schools and that those among this group who live in wholly selective areas but don’t attend grammar schools perform worse than the national average, and that if you compare high attaining pupils in grammar schools with similar pupils who attend high quality non-selective schools, “there are five times as many high quality non-selective schools as there are grammar schools”.

The impact of selection can last a lifetime; several studies have found that earnings inequalities “are wider for children born in selective areas during the 1960s and 1970s as compared with those born in comprehensive areas. This comes from a combination of higher wages at the top of the distribution for individuals who grew up in selective areas and lower wages at the bottom.”

The evidence from those fully selective counties that still use the 11-plus presents a bleak picture of large areas cleaved by social class, and often ethnic background, with family income playing a large part in ensuring success in pre-secondary level selective tests. Class is clearly the biggest factor in terms of exclusion from selective education, with more complex cultural and ethnic patterns at play in different parts of the country. New Sutton Trust analysis of recent Department for Education data shows that “when it comes to entry into grammar schools, white British disadvantaged children have the lowest rate of entry to grammars among a range of ethnic groups. Disadvantaged Indian, Chinese and other Asian children attend grammars at much higher rates than white British pupils. On average over the last five years, disadvantaged Asian pupils have been three times more likely, Indian pupils have been four times more likely, and Chinese pupils fifteen times more likely to attend grammars than their disadvantaged white British counterparts.”

But the picture shifts in subtle ways from selective county to selective county as we learn from the work of Local, Equal, Excellent (LEE) in Buckinghamshire, an organisation affiliated to Comprehensive Future. Through careful gathering of data over several years Local, Equal, Excellent has established that ‘Buckinghamshire’s 11+ test contains clear and substantial bias” against certain groups of children. After the introduction of a new 11-plus exam in 2013, LEE found no change in the already established “patterns of unfairness.” In fact, “The evidence suggests that the new 11+ exam has made no difference in addressing the following trends in Bucks, and indeed shows that some trends are getting worse” including declining pass rates for Bucks state school pupils, a large gap between the average pass rates of the poorer and wealthier areas of Bucks, much lower pass rate for children on Free School Meals, and much higher pass rate for children at private schools.

Looking at test results from 2014 and 2015, LEE found that in both years children from Pakistani backgrounds performed significantly worse in the exam than the majority of other children, and were only half as likely to pass as White British children. Crucially, the bias against children from certain ethnic backgrounds was also against high ability children from these backgrounds. A report provided by the test provider (Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University) in response to a FOI request, cites three Bucks primary schools where nearly all of the children are from Pakistani background. At these schools, 46 children were categorised as ‘high attainers’ according to their KS2 results, but only seven of these children passed the 11+.

In the group’s response to this green paper consultation LEE can assert with some confidence that “there is no evidence that grammar schools have succeeded in using ‘much smarter tests”. Outcomes data from the first four years of the new test in Buckinghamshire have shown quite clearly that results for children from poorer homes have got no better, and that private school children have made gains while state school children have done worse. The government’s own Chief Scientific Adviser, Dr Tim Leunig, has conceded this failure of Buckinghamshire’s new ‘tutor proof’ test. In November 2016, he told the House of Commons Education Select Committee, “I don’t want to cast any aspersion on their reasons for doing it or on the people who designed the test [CEM], but it didn’t work.”

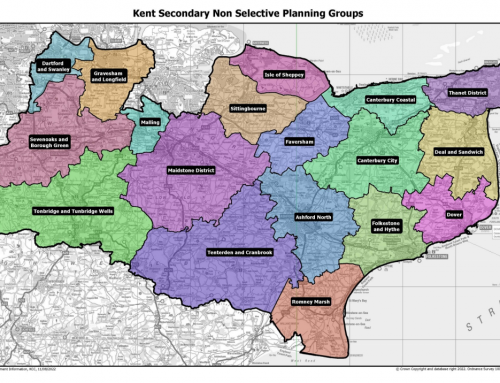

Among its many objections to selection in Kent, the Kent Educational Network (KEN), another affiliate of Comprehensive Future, states that the Kent (11 plus) Test is “unreliable, unscientific, and labels children in a way that is not helpful to their future ambitions. No child can be judged accurately in a test at age ten or eleven”. Selection also cements an unhelpful class divide. “44% of parents admitted to paying for Kent Test tutors in a 2013 Kent survey. 13% of pupils in grammar schools were educated in independent schools. Just 3% of children in Kent grammar schools are classed as ‘disadvantaged’ compared to 18% in the county’s non-selective schools. We believe every child deserves a good education, but our system limits opportunity for disadvantaged children and benefits wealthy parents.”

As Joanne Bartley of KEN wrote recently in the Guardian, “ There is endless evidence that this exam merely rewards those who can afford to pay for tutoring. Primary schools do not give up time to prepare children for the tests. Meanwhile tutoring costs £30 an hour. In a recent survey, 44% of parents who responded said they used tutors. You must not be reading the evidence or else find it acceptable that a school place can be bought in this way”. Last year, the Birmingham Mail reported that parents were spending up to £5000 to ensure their children’s success in tests for entry to the city’s grammar schools.

According to KEN, selection lets down the majority of Kent’s pupils, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, “Kent’s education system produces no better results for our children. 57% of Kent children achieve 5 A-C GCSE passes, just the same as the UK average. However, Kent’s disadvantaged pupils achieve far worse results than average. 30% of disadvantaged pupils achieve 5 GCSE passes in Kent, while the national figure is 37%. At A level Kent pupils also under perform. In Kent 73% of students achieve 3 A levels, but the UK average is 77%. Our divided school system means many of our non-selective schools can not offer good A level options.”

It is by now very well established that grammar schools currently take very low numbers of children on free school meals. Less than 3% of entrants to grammar schools are entitled to free school meals. In 98 of the 163 grammar schools there are between 1-3% of pupils eligible for free school meals: 21 schools have less than 1% of children on free school meals. According to Education Datalab, “ Overall, 1,402 out of 22,497 pupils at the end of KS4 in grammar schools were disadvantaged, or 6%. For comparison, across all schools nationally we think around 27% of children in Year 11 had been eligible for free school meals in the last six years.”

Conversely, as evidence from our affiliated organisations in the selective counties brings out again and again, a higher proportion of children in grammar schools come from private preparatory schools. As Education Datalab found “Overall, we think that a little less than 3,000 of the 22,497 children at the end of KS4 at grammar schools in 2014/15, or around 13%, had attended prep school, versus the 6% who were deprived. (Looking at Year 7 entrants to grammars in 2014/15, the prep school figure appears a little lower, at around 11%.)”. Even high achieving children from disadvantaged backgrounds are unlikely to get into existing grammar schools. Amongst those getting the top scores in English and Maths at age 11 in grammar school areas (level 5 in both in English and Maths), only 40% of children from poorer families went on to grammar schools, compared with 66% of their richer counterparts.

A selective system creates unnecessary anxiety in both winners and losers. It affects the atmosphere of primary schools as children are unofficially, and then officially, ‘sorted’ into so-called successes or failures from a young age, and creates stress in the home life of those who are tutored for the test with parents often spending large amounts of money in coaching them to get through. For those children who do not get through the test, effects can be long lasting, as stories gathered from the selective areas by Comprehensive Future (and presented to MPs and Peers at the House of Commons in October 2016) show. According to one parent, “It is totally naive to think that the system does not impact on the self-esteem of entire families, or that secondary modern schools can provide the same level of experience as grammar schools where alumni and parents are ploughing thousands of pounds a year into the PTAs.” Another writes: “Our son has dusted himself down but I don’t think he will ever get over his ‘failure’. We try to tell him it wasn’t a failure and it’s just a silly system, but it has knocked his academic confidence for years. We hope he can pick his confidence back up for the GCSE exams soon. What a strange system it is which kicks children in the teeth at the age of ten at the very time we should be building their confidence and starting to prepare them for the dynamic world in which we live.”

Q: What can we do to support the creation of either wholly or partially new selective schools?

Q. How can we support existing non-selective schools to become selective?

We shouldn’t. Both these questions fail to address the real challenges facing our education system.

The creation of new selective schools, or the conversion of existing non-selective schools into selective institutions, would have a highly damaging impact on neighbouring schools in those areas which are currently comprehensive in intake. It would return large parts of the country to a divisive system that the majority of parents, teachers and pupils rejected over half a century ago. Support for the move towards comprehensive schooling in the 1960s and 1970s gained the backing of local authorities from across the country and from all political parties with many Conservative voting parents rising up against a system that rejected their children and designated them as second-class pupils, a situation that might well arise in the future if the government decides to move back to selective education. As Simon Burgess, Professor of Economics at the University of Bristol has pointed out, as regards the current proposals, “if say 25% of kids go to grammar schools, large numbers of middle class kids will be finding themselves in secondary moderns.” These families are likely to be the first to revolt.

Since its inception, comprehensive education has proved a resounding success, providing millions of young people with the chance to gain key qualifications and move on to further study. At the height of the so-called ‘golden age’ of grammar schools, only 9% of all school pupils left school with 5 ‘O’ levels. Nowadays, just under 60% of all state school pupils attain five or more A*-C grades at GCSE, the vast majority of them educated in comprehensive schools. By refusing to label the talents and skills of children at too young an age (10/11) a comprehensive system gives every pupil the chance more fully to develop their potential.

We can see this by comparing the educational achievements and quality of schools in broadly comparable areas with very different school systems. The counties of Hampshire and Buckinghamshire are broadly similar in population and political make-up. Hampshire chose to go comprehensive in the 1960s while Buckinghamshire opted to continue with a selective system which it operates to this day. As Nuala Burgess shows in her forthcoming report on the educational trajectory of Hampshire and Buckinghamshire, A Tale of Two Counties – to be jointly published by Kings College, London and Comprehensive Future in January 2017 – more pupils get better grades in non-selective areas, especially moderate and low attainers. Middle and low attainers in selective Buckinghamshire fare far worse in their GCSEs, for example, than middle and low attainers in non-selective Hampshire. Burgess states that “While in Hampshire, the 2015 average capped GCSE score of middle attainers was 298, in Bucks it was 293. With low attainers, the difference is more marked, with Hampshire’s low attainers achieving 188 to Buckinghamshire’s 167.”

Despite government claims that disadvantaged children, who make up only a tiny percentage of grammar pupils, do better in selective schools, their outcomes are still, on average, worse than their wealthier peers in the same school. The LEE response to the green paper consultation points out that the 2008 CEM report relied on so heavily by the government in this green paper cautioned against attributing the good progress of disadvantaged children at grammar schools to the fact of them being at a grammar school. The same factors that propel a disadvantaged child to be in the tiny minority of children from similar backgrounds who succeed in gaining entry to grammar school may well be the factors that then ensure they do well.

Education Datalab finds that grammars tend to have a relatively low proportion of Pupil Premium pupils who are long-term disadvantaged (defined as FSM-eligible for 80+ percent of their school career) compared to comprehensives: 18 per cent vs 35 per cent. “Poverty experienced over a long period leaves an indelible mark on a child’s school career. A lower trajectory of achievement is not inevitable for long-term disadvantaged pupils, but it will require exceptional schools to change it. Even if all grammar schools were capable of doing this (which the above analysis suggest they are not), it is clear that long-term disadvantaged pupils are not able to access them in anything like the numbers needed to overturn the attainment gap.”

Education Datalab also disputes claims that grammar schools have much better Progress 8 outcomes than other kinds of schools. For those children who get relatively low Key stage 2 results but pass the 11-plus, their progress scores at GCSE often seem “incredibly high” but according to Dr Rebecca Allen, director of Education Datalab, this “almost certainly understates their academic ability at age 11. Some of the progress made during primary school is then unfairly attributed to their grammar school.” The opposite is true for pupils with high key stage 2 results who failed the 11-plus, suggesting their SATs scores are over-estimated. As Allen avers, “Some of the progress at their secondary modern is therefore unfairly attributed to their primary school.”

Most educational experts, nationally and internationally, agree that the way to raise the overall performance of England’s pupils, and particularly those of disadvantaged students, is to concentrate on improvements in all schools. According to the September 2016 EPI study, “other interventions to raise school standards and attainment have proven to be more effective than grammar schools in raising the attainment of disadvantaged pupils.” There are, within the educational world, differing views as to the best ways to create and sustain school improvement; however, there exists a broad consensus that sufficient teachers of high quality, good school leadership, positive discipline, class sizes and collaborative schemes like the National and London Challenge have had significant success in raising standards, most notably for pupils from disadvantaged homes.

In its Gaps in Grammars report, published in December 2016, the Sutton Trust finds that “compared to high performing comprehensive schools, there is no benefit to attending a grammar for high attaining pupils… the highly able perform just as well in good comprehensives as they do in grammars.” The report therefore concludes that “From a social mobility perspective, investing in the large numbers of highly able students in comprehensives across their whole time in secondary schools is likely to bear more fruit.” The Institute for Fiscal Studies agrees: “ Inner London…has been able to improve results amongst the brightest pupils and reduce inequality. This suggests that London schools probably offer more lessons on ways to improve social mobility than do grammar schools”.

David Willetts, former education spokesperson for the Conservative party, has put the same argument in opposing the return of a more widespread selective system: “If you look overall, not just in Britain but around the world, at those school systems we admire that have got high performance and high standards, from Shanghai to Finland, by and large they don’t put their effort into trying to pick which kids they educate; they put their effort into raising standards for all the kids.”

Echoing the words of Sir Michael Wilshaw, the outgoing Chief Inspector of Schools, and one of the most prominent opponents of a return to selective education, David Willetts states that “When it comes to the best education policies we should look at the evidence and we’ve got some very good evidence close to home: look at the transformation of schools in London…..Those are really tough areas in London where they’re actually achieving higher educational standards than in Kent and without selection”.

There are also important social benefits to comprehensive education. High performing, but inclusive, comprehensive schools play an important part in promoting social cohesion and greater ethnic and religious tolerance and understanding as well as providing more educational chances for those from poorer backgrounds. In our increasingly fractured society, with political, ethnic and religious tensions rising this must surely be an important consideration for government.

Writing to the Guardian newspaper on December 5th 2016 in relation to the findings of the Casey Review into opportunity and integration, Katy Simmons, a governor of a non-selective school in Buckinghamshire, makes the important point that the review “doesn’t seem to have looked at the evidence of the current impact of grammar schools on opportunities and integration.” Simmons continues: “ If (Casey) had looked at Buckinghamshire, where there is educational selection at 11 across the whole county, all the evidence is that it divides communities on the basis of social class and ethnicity. Evidence collected over several years shows that Buckinghamshire’s 11-plus test contains clear and substantial bias against children from certain ethnic groups, in particular children of Pakistani and black Caribbean heritage.

The way to improve school quality is not to further divide children – or neighbourhoods or entire counties – using unreliable methods of assessment of so-called ability but to invest in high quality comprehensive education. Funds that are currently earmarked for expansion of selective education, approximately £50 million a year, would be far better spent increasing the recruitment of teachers and school leaders, ensuring there are sufficient school places, reducing class sizes and reforming the 14-19 curriculum to ensure a broad and stimulating education for all. In its report on the 2016 PISA results, OECD education chief Andreas Schleicher highlighted concerns about the impact of teacher shortages in England, pointing out that an education system can never exceed the quality of its teachers and warning that head teachers in this country saw a teacher shortage as “a major bottleneck” to raising standards.

Q Are these the right conditions to ensure that selective schools improve the quality of non-selective places?

No. The expansion of selective school places will inevitably have a damaging effect on the quality of non-selective places, for some of the reasons given above. Some local areas are already mobilising against such an eventuality. Excellent Education for Everyone, a group of residents in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead and another local affiliate of Comprehensive Future, campaigns to defend the borough’s comprehensive schools against the damaging encroachment of selective schools. Among the group’s aims is to “support all of Maidenhead’s Secondary Comprehensive and Free Schools, to encourage and demonstrate the value of top comprehensive schooling, demonstrate the unjust nature of the 11+ tutorial system and the lasting damage it can do to our children, and examine the … effect of introducing a state grammar school into a previously geographically comprehensive area, on existing schools.”

Excellent Education for Everyone makes an obvious but important point: wherever selection exists, or is introduced, the education of those who are not in grammar schools is inevitably damaged. As a series of experts, giving evidence to the House of Commons Education Select Committee in November of this year, made clear, it is much harder for non-selective schools to recruit teachers; these teachers are often less qualified; children who start their secondary career on the basis of failure struggle with self-esteem and have low educational expectations; there is often a ‘peer to peer’ effect in these schools, with lower social capital and concentrated problems of behaviour.

There is also no evidence that selective schools can help raise the achievements of nearby non-selective schools. Perhaps the most recent example is that of Bright Futures, an academy chain set up by Altrincham grammar school for girls, which has failed to ‘turn around’ Cedar Mount academy, a non-selective school in a much tougher part of Manchester. According to the Guardian, “Cedar Mount academy has been in special measures for 18 months, despite being in the Bright Futures chain – praised as transformational five years ago by then education secretary Michael Gove. The school has seen the proportion of pupils passing English and maths GCSEs drop for four years in a row. Meanwhile, Education Guardian can reveal, an analysis of official data on the Ofsted results of schools already in academy trusts – including a selective school – suggests grammars have yet to pass on their impressive record of inspection success to other institutions.”

Q: What is the right proportion of children from lower income households for new selective schools to admit?

Again – the wrong question. Yes, there are shockingly few children from low income families within today’s grammar schools, in part because the 11-plus inevitably tests what a child already knows (rather than their potential to learn) which benefits pupils from better off households or from those families who can pay for tutoring.

However, current evidence from Buckinghamshire suggests that it is not possible to devise a ‘tutor proof’ test (see above). Furthermore, according to Dr Rebecca Allen, of Education Datalab, giving evidence to the Select Committee in November 2016, a supposedly ‘tutor proof’ test would most likely involve parents with deeper pockets investing more, not less, in making sure their children got through the exam. The Committee also heard that relying on teacher preference is likely to set up intractable problems for both primaries and secondaries, with parents certain to challenge the criteria by which schools choose whom they consider ‘worthy’ of a grammar school education. It is also surely likely to result in more, not fewer, children from advantaged homes being chosen for a selective education.

Suggestions made by government and others that schools should lower their pass mark in order to admit a proportion of children from lower income families opens up another can of worms. How many children will be let through on this ‘lower test mark’ criteria? If significant numbers of children are let in on a lower test result, might not parents from better-off homes, whose children receive a higher pass mark in the 11-plus but are refused a place, launch a legal challenge against a school, or indeed the government, for denying their offspring a place at a much coveted grammar?

There is also an illogicality at work in lowering the passmark in order to allow a greater range of children into the school. One could argue that this moves a selective institution towards becoming a non-selective one so why not just phase out selection altogether and make the school comprehensive? Alternately, allowing in only a handful of children poorer homes on a lower pass mark, as Buckinghamshire’s grammars now propose to do, smacks of the worst sort of tokenism, and does not solve the underlying problem at all.

In addition, ensuring that only children on free school meals or in receipt of the Pupil Premium have a right to entry on the basis of a lower pass mark would bypass the millions of children from ‘ordinary’ hard pressed families who do not qualify for state benefit but are far from affluent. According to Gaps in Grammar, published by the Sutton Trust in December 2016, “the ‘just about managing’ families, which the prime minister has said she wants to prioritise……were substantially less likely to attend grammar schools…. than children from better off areas.“ Lack of access to grammar schools isn’t merely restricted to those at the very bottom of the scale.

Q: Are these sanctions the right ones to apply to schools that fail to meet the requirements?

Q: If not, what other sanctions might be effective in ensuring selective schools contribute to the number of good non-selective places locally?

There is no evidence that selective schools can improve the quality of non-selective schools and, in fact, considerable evidence that their very existence harms the education of other children, particularly in closely neighbouring schools. Therefore, for government seriously to propose sanctions against grammar schools, operating within an officially approved selective system, is a suggestion that borders on the Kafkaesque.

Q: How can we best ensure that the benefits of existing selective schools are brought to hear on local non-selective schools?

We can’t.

Again, this is the wrong question. We should instead be looking at how all schools can improve. For this, government should increase funding to areas that need them most ( without penalising other areas), concentrate on recruiting the best qualified teachers, particularly to poorer neighbourhoods and schools and foster collaboration, not competition, between local schools.

Q: Are there other things we should ask of existing selective schools to ensure they support non-selective education in their areas?

No. Selection should be phased out of the English education system entirely and all our schools improved along the lines suggested above.

Q: Should conditions we intend to apply to new or expanding selective schools also apply to existing selective schools?

No. Selection should be phased out of the English education system entirely and all our schools improved along the lines suggested above.

Rarely has a government proposal met with such forceful and largely united opposition within the educational world. Over the past few months, a host of experts, professionals and organisations have come out against the ideas put forward in this Green Paper. These include Sir Michael Wilshaw, the Chief Inspector of Schools, head teachers in Surrey and Kent, Oxfordshire Council, Teach First, the Fair Education Alliance, to a range of academics and educational leaders from Professor Becky Francis, Director, UCL Institute of Education, Professor Sandra McNally, Director Education and Skills, Centre for Economic Performance, at the London School of Economics and Simon Burgess, Professor of Economics, University of Bristol.

If these proposals are put in place, they will exacerbate the divide between non-selective and selective state schools, entrench the division between ‘academic’ and ‘vocational’ areas of the curriculum, lead to greater inequalities of educational opportunity, income and wealth, intensify current levels of social division and alienation and lead to lower overall levels of national attainment.

For all these reasons, Comprehensive Future believes this is a deeply flawed policy that should be set aside immediately if the government is sincerely and seriously concerned to create, and sustain, schools that work for everyone.

Comprehensive Future

December 2016