1. One argument often put forward by supporters of selection is to say that the alternative is selection by mortgage and therefore by income as parents move to be near certain schools. Selection they say would be fairer. One study indicated that there might be a 20% difference in house price, a premium parents were willing to pay (i). However research in 2010 indicated that although some parents do move to be nearer schools this is only a relatively minor factor in decisions to move house(ii). However other researchers have found that parents do move house to get a good school(iii). But some of the highest rises in house prices are in the catchment of grammar schools!(iv) It is important to point out that when the 11 plus results come out it is the child who gets the message of failure. At least if parents do not buy a house in a particular area children do not feel they have failed.

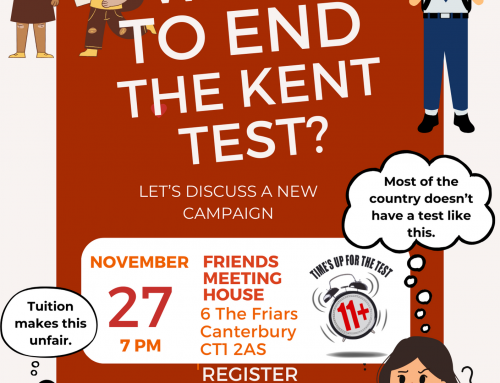

2. In any case the cheque book plays a major part in selection as parents pay to have their children coached or send them to prep schools to be given intensive preparation for sitting the 11plus. Many whose parents can afford it are coached for long periods (v). Research shows that children who are coached are more likely to pass the test (vi). In 2013 research for the Sutton Trust showed that more than four times as many grammar school pupils come from outside the state sector (with the vast majority likely to be from fee-paying preparatory schools) than the number entitled to free school meals (vii).

3. Although attempts have been made by some authorities to introduce a ‘tutor proof test’ it is thought unlikely that such tests can be produced (viii). More seriously in Bucks it has been shown that so called tutor proof tests have resulted in even more children from private schools ‘passing’ the test. The campaign group Local Equal and Excellent in Bucks has shown again that grammar schools do not boost social mobility and a new “tutor-proof” test has done nothing to stop children from wealthier backgrounds being coached to win places at selective schools (ix).

4. ‘Passing’ the test is related to the number of grammar school places available in any given area, it is possible for a child to ‘pass’ in one area and ‘fail’ in another. Areas defined as selective vary from 40% to 25% of their secondary places being in selective schools (x).

5. Primary schools are comprehensive but when poorer children or those with special needs go on to secondary education their parents find that selection divides them off. The proportion of children eligible for free school meals in grammar schools and with special educational needs is much smaller than in all secondary schools (xi).

6. Research on the transfer test in Northern Ireland (the Northern Ireland 11 plus) found it to be neither reliable nor fair. Researchers said that more than 30% of pupils who took the Transfer Test could be assigned the wrong grade (xii). Testing was found to be related to past experience rather than future potential.

7. There has been considerable interest in the work of Robert Plomin on heredity and intelligence but he has not said his work supports the idea of children being divided by a test at 11. Rather as has been said in comments by other academics this work supports the trend in education toward personalised learning rather than a one-size fits all model (xiii).

8. Writing in 2015 Professor Chris Husbands outlined the four assumptions which need to hold for the argument in favour of grammar schools to be sustainable. Firstly that a test at age 11 will reliably discriminate between those who are academically able and those who are not when in fact all tests have a high error rate, either because the tests do not measure accurately what they purport to assess, or because of random variations in performance on the day of the test, or because of marker error. Secondly that it is possible to test for academic ability at age 11 in a way which is valid – that is, that a test performance at age 11 will be strongly predictive of performance later when the evidence is that children develop at different speeds and in different ways: those who perform well on a test at age 11 may not perform well at 12; those who perform relatively badly at 11 may perform better at 12. Thirdly that it is possible to design tests which have high specificity – that is, that they test academic ability and nothing else, such as socio-economic status. But the evidence is to the contrary: poorer children have always been under-represented in grammar schools. Lastly that it is possible to identify a defined group of pupils who will benefit from a grammar school education by comparison with the rest of the population. When grammar schools were widespread, the selected proportion varied hugely from area to area and it still does: approximately six per cent in the Birmingham grammar schools and, just 20 miles away, about 30 per cent in Rugby. Both cannot be correct. He goes on to say there is no academically credible argument in favour of selection for grammar schools at age 11 (xiv).

9. The 11 plus adds another stress to children already facing SATs. As the review body looking at the effect of the 11 plus in Northern Ireland said – ‘We were particularly impressed by the views of young people about their experiences of the Tests and their effects on themselves and others. We have been left in no doubt that the Tests are socially divisive, damage self-esteem, place unreasonable pressures on pupils, primary teachers and parents, disrupt teaching and learning at an important stage in the primary curriculum and reinforce inequality of opportunity’. The report went on to say – ‘the selection (and separation) of pupils on a narrow academic basis, at such an early stage in their education career, is both inappropriate and unsustainable. In reaching this view, we have had regard also to the implications of the European Convention on Human Rights’(xv).

10. Text anxiety clearly affects performance (xvi). There is no need to put children through this unnecessarily when comprehensive education avoids the pass or fail cliff edge of the 11 plus. Tests such as the 11-plus can affect self-esteem and have a detrimental effect upon learning. Neuroscience provides an explanation of how learning is affected by emotion xvii. When children are stressed the hormone cortisol inhibits memory and thinking (xviii).

11. There is comparative evidence to suggest that how children label themselves affects their learning. Wilkinson & Pickett highlight the US experiment where children were persuaded that eye colour influenced intelligence and performed accordingly in tests (xix). Failing at 11 must damage children’s aspirations. Research for Rowntree found that secondary school pupils are more likely to do well at GCSE if they have belief in their ability (xx).

12. Select affects communities and social cohesion. Where schools select, social segregation increases, that is, some schools have a much higher proportion of children from poorer families than others. Drawing on research from several sources Coldron said ‘The evidence concerning selection and overall attainment is complex but it is clear that it contributes substantially to social segregation without any significant balancing educational benefit’. He found that the most highly selective local authorities had more socially segregated schools, fewer parents gaining their first preference and more appeals (xxi). Similarly work by Allen and Vignoles from LSE found local authorities with more schools that controlled their own admissions or had explicit selection by ability had a higher level of social segregation (xxii).

13. A comparison of the social segregation in England’s secondary schools with other OECD countries by the Statistical Sciences Research Institute in Southampton showed that England is middle ranking in terms of social segregation (xxiii). Countries which had higher levels of social segregation such as Austria, Holland, Germany and Hungary have selective school systems. Countries such as the Nordic countries and Scotland have less segregation than England and the researchers conclude this is because of their non-selective school systems. Other research (xxiv) drawing on many international studies found that selective systems have higher levels of social segregation and more unequal educational outcomes and that social cohesion is affected. A later OECD report said that the UK had some of the most socially segregated schools (xxv).

Refs

i Leech, D and Campos, E. (2003) Is comprehensive education really free? Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 166 Part 1.

ii Allen,R, Burgess, S and Key,T (2010) Choosing Secondary School by moving house, Working Paper 10/238, Centre for Market and Public Organisation, Bristol.

iiiFrancis, B and Hutchings M (2013) Parent Power? Using money and information to boost children’s chances of educational success,

iv Financial Times (4th September 2015) House price premium near top UK schools hits £41, 000

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/e208975a-5258-11e5-b029-b9d50a74fd14.html#axzz3qpLq7GqE

v Asthana A, (2009) Early starts for the children desperate to pass their 11 plus. Observer

http://www.theguardian.com/education/2009/oct/11/grammar-schools-tuition-private-tutor

vi Vernon, P.E. (1950) The Structure of Human Abilities, Wiley.

Bunting,P and Mooney, E, (2001) The Effects of Practice and Coaching on TestResults for Educational Selection at Eleven Years of Age, Educational Psychology, Vol 21,(3).

vii Cribb, J, Sibieta, L, Vignoles, A, Skipp A, Sadro F and Jesson D. (2013) Poor Grammar: Entry into Grammar Schools for disadvantaged pupils in England. Sutton Trust

viii Tutors International (2015) If the CEM 11+ exam is tutor-proof why are parents so anxious to secure a tutor? PR Web

http://www.prweb.com/releases/2015/01/prweb12421978.htm

ix Barker I, (2015) Does ‘tutor-proof’ 11-plus let down the disadvantaged? ?Times Educational Supplement

https://www.tes.com/article.aspx?storyCode=6453308

Cassidy, S (2015) Grammar Schools do not boost social mobility. Independent

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/grammar-schools-do-not-boost-social-mobility-report-says-a6697401.html

x Nick Gibb MP (6 March 2012) Grammar School Admissions, House of Commons Parliamentary Answer to Lisa Nandy MP.

xi Nick Gibb MP (26 April 2011) Grammar Schools: Disadvantaged, House of Commons Parliamentary Answer to Bill Esterson MP; Diana R Johnston MP (30 June 2009) Pupils: Disadvantaged and Special Educational Needs, House of Commons Parliamentary Answer to Paul Holmes MP

xii Gardner,J and Cowan,P, (2000) Testing the Test Queens University Belfast.

xiii Plomin, R and Deary,I J (2014) Genetics and intelligence differences: five special findings. Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 98–108;

http://www.nature.com/mp/journal/v20/n1/full/mp2014105a.html

Krapohl, E and Rimfeld, K (2014) How genes can influence children’s exam results. The Conversation.

http://theconversation.com/how-genes-can-influence-childrens-exam-results-32535

xiv Husbands. C (2014) Selection at 11 – a very English debate. IOE London Blog

v Report of Post Primary Review Body (2001) Education for the 21st Century, Northern Ireland Dept of Education

xvi McDonald, A.S.(2001) The Prevalence and Effects of Test Anxiety in School Children, Educational Psychology, Vol. 21, No. 1.

xvii Zull, J. (2002) The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching the Practice of Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning ,Stylus Publishing.

xviii Gerhardt, S. (2004) Why Love Matters: How Affection Shapes a Baby’s Brain, Routledge

xix Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2009) Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, Allen Lane.

xx Goodman,A and Gregg, P (2010). The importance of attitudes and behaviour for poorer children’s educational attainment, Joseph Rowntree Foundation

xxi Coldron, J et al. (2008) Secondary schools admissions, Research Report DCSF-RR020 DCSF

xxii Allen,R.and Vignoles, A.(2006) What should an Index of School Segregation measure? Centre for the Economics of Education. LSE

xxiii Jenkins, S.P., Micklewright, J and Schnepf, S. (2006), Social segregation in secondary schools: how does England compare with other countries? Southhampton S3RI

xxiv LLAKES Centre for Learning and Life Chances in Knowledge Economies and Societies (2011), Education, Opportunity and Social Cohesion, ESRC, Institute of Education, London

xxv Garner R (2012) UK schools some of the most socially segregated in the world. Independent

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/uk-schools-the-most-socially-segregated-in-the-world-8125908.html