In August 2016 Fiona Millar issued a challenge saying that if the Government wants more grammars and has evidence in support they should ‘bring it on’. But unsurprisingly little evidence apart from anecdotes has emerged in support and what we have seen is more and more solid evidence against selection.

In September 2016 Luke Sibieta of the Institute of Fiscal Studies looked a wide range of evidence including research from Northern Ireland. He concluded that ‘Grammar schools therefore seem to offer an opportunity to improve and stretch the brightest pupils, but seem likely to come at the cost of increasing inequality. Inner London, by contrast, has been able to improve results amongst the brightest pupils and reduce inequality. This suggests that London schools probably offer more lessons on ways to improve social mobility than do grammar schools.’.. The expansion of selection ….will create a distraction from a more fundamental problem of school improvement across the spectrum. A more constructive policy would be to initiate the challenge and support required to reduce the variation between schools. Simply replicating the structure of how schools admit pupils is not a recipe for better attainment’.

In November 2016 the Social Mobility Commission published its Annual Report – State of the Nation. It said ‘…, the current Government has a desire for all schools to become academies and is now proposing to create new grammar schools. The focus on grammar schools, like the drive for all schools to become academies, is, at best, a distraction and, at worst, a risk to efforts aimed at narrowing the significant social and geographical divides that bedevil England’s school system. The Commission is not clear how the creation of new grammar schools will make a significant positive contribution to improving social mobility. We recommend that the Government rethinks its plans for more grammar schools and for more academies. The Commission hopes that the Government will move on from an over-reliance on structural reform to a new and relentless focus on improving teacher quality and fairly distributing teachers to the schools that most need them. The Government’s failure to take responsibility for delivering a high-quality and fairly distributed teaching workforce continues to be the most significant weakness in its approach to schools. For poor children, the difference between a good and poor teacher is equivalent to one year of learning.’

December 2016 saw quite a flurry of publications as the consultation on the Green Paper ended. Stephen Gorard and Nadia Siddiqui at Durham University using the full 2015 cohort of pupils in England, found ‘ how stratified the pupils attending grammar schools actually are (worse than previous estimates) in terms of poverty, ethnicity, language, special educational needs, and even their age in year. It also shows that the results from grammar schools are no better than expected, once these differences are taken into account.

For example the researchers found that ‘the characteristics of pupils attending grammar schools are markedly different in many ways from those attending other state – funded schools in England. Those attending grammar schools, on average, live in less deprived areas, are older in their year group, and even where they are FSM eligible they will have been so for fewer years’.

They concluded that ‘There is no evidence base for a policy of increasing selection; rather the UK government should consider phasing the existing selective schools out’.

They went on to say ‘This is not to decry the schools that are currently grammars, or the work of their staff. But overall, they are simply no better or worse than the other schools in England once their selected and privileged intake is accounted for. Nor do the findings of this paper and others mean that schools should not use any form of internal ‘setting’ by ability in any phase. In the absence of grammars it is still currently possible for high ability pupils to be taught together for at least some of the week (and whether that is an effective approach would be another paper). But the richer and more able pupils currently in grammar schools would then mix with a wider range of peers ,especially those with learning challenges, to the mutual benefit of all, in all classes and years that did not use setting, all vertical structures such as ‘houses’, and in sports, play and extra curricular activities. The importance of inclusion is not just about those with learning difficulties or disabilities; it can also be about the most able at age 11.’

Education Datalab has carried out a great deal of analysis on the comparative achievement of grammar schools. It its response to the Green Paper in December it concluded as a result that – ‘the expansion of selectivity in England’s education system is not the right way to raise standards for all; currently, selective schools admit disproportionately few children from low income households. We do not have confidence that policies proposed in the consultation document would address this issue satisfactorily;’

In December the Sutton Trust published a research brief on grammar schools. Among the findings in Gaps in Grammar it reported that ‘Attainment in GCSEs is higher in grammars than comprehensives, for both disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils. However, much of this is attributable to high levels of prior attainment of the pupils entering grammars. Highly able pupils achieve just as well in top comprehensives as they do in grammar schools.’

At the same time the author of this report, Carl Cullinane, having looked at even more evidence concluded that ‘It is therefore questionable whether increased selection would lead to more good school places overall, rather than the concentration of previously high attaining students and high quality teachers in a small number of schools, while others suffer in comparison. Ministers rightly want to tackle the issue of low attendance at top universities of disadvantaged children. However, a better way to do this may be to boost the attainment and aspirations of highly able pupils across all comprehensives throughout their secondary education. The best candidates for support are not necessarily those that reveal themselves in the 11 plus. Taking the evidence as a whole, it’s clear that grammars are no quick fix for England’s social mobility problems.’

The Royal Society commissioned research from the Education Policy Institute to look at the likely effect of more grammars on the uptake of STEM subjects. In its response to the Government’s green paper the Society said – ‘From the research we have commissioned, we have found no evidence to suggest that overall educational standards for STEM subjects in England would be improved by an increase in the number of places in selective schools. Nor have we found evidence that the number of students progressing to STEM subjects in higher education would increase as a result of these proposals’.

Also in December the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology published a briefing on ‘brief overview of methodologically robust studies on state-funded selective schools that select the majority of their intake on academic criteria.’ It did not draw any conclusions but did not seem to find any studies which supported the Government’s proposals.

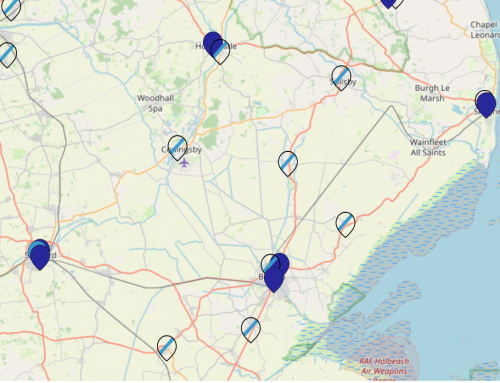

Several publications by the Education Policy Institute (EPI) have cast doubt on the advisability of the Governments proposals. In September 2016 its researchers concluded that ‘Overall, this analysis supported the conclusions reached by the OECD for school systems across the world – that there is no evidence that an increase in selection would have any positive impact on social mobility’.In December 2016 the EPI tried to find areas which might benefit from more grammar schools but concluded ‘that the Government’s present stated strategy of expanding existing grammar schools is likely in a majority of such areas to reduce the average attainment of disadvantaged pupils and is therefore unlikely to improve social mobility. A more promising approach in the most disadvantaged and low attaining areas may therefore be to focus on increasing the quality of existing non selective school places, as has been successfully achieved in areas such as London over the last 20 years.’ At the same time the EPI also looked at the issue of ‘tutor proof tests’ and concluded ‘in practice, therefore, it seems highly unlikely that the effects of additional tutoring, or indeed the quality of primary school and home learning environment, can ever be fully eliminated and, whilst it may be possible to design tests which are more widely accessible, there does not yet seem to be a clear understanding of the most effective mechanisms for achieving this.’

In an article in February this year EPI chair David Laws summarised some of EPI’s work on the Government’s proposals. He said – Because almost 40% of the disadvantage gap emerges before entry to school, and around 60% emerges by the end of primary school (Education Policy Institute Annual Report 2016), any social mobility solution based on selection of highly able students at age 11 isn’t likely to be very effective. Only 2.5% of grammar school pupils are entitled to free school meals – a key measure of poverty – compared with 13.2% in all state funded schools….. Importantly, our research also showed that in the most selective areas we begin to uncover a small negative effect of not attending a grammar school. For pupils who live in the most selective areas but do not attend a grammar school, negative effects are estimated to emerge at around the point where selective places are available for 70% of high attaining pupils – which is a concern given that the government has indicated that it will prioritise grammar school expansion in the areas where these schools are most popular, which is largely where grammar schools are already prevalent.

He went on to say – EPI researchers compared high prior-attaining pupils in grammar schools with similar pupils who attend high quality non selective schools. These are schools in the top 25 per cent based on value-added progress measures, and represent good quality schools operating at large scale. There are, according to our calculations, five times as many high quality non-selective schools as there are grammar schools, based on this measure. These schools also turn out to be much more socially representative than grammar schools, admitting close to the national rate of FSM pupils (12.6% versus 13.2% nationally). Compared with these high performing non selective schools, we estimate there is no benefit to attending a grammar school for high attaining pupils, measured by “best 8” GCSE grades. There is therefore a strong case for the government seeking to prioritise the creation of more high performing non selective schools, particularly in those parts of the country where the attainment of low income pupils is very poor.

Several other organisations have produced useful information and links to evidence. School Dash asked the question if grammar schools can work for everyone and after looking at the effect of grammars on surrounding schools it concluded that ‘On the basis of the evidence presented here, grammar schools clearly don’t work for everyone’. Full Fact examined the data and provides links to earlier work. The Fair Education Alliance has publications summarising the data and evidence against selection as well as campaigning material.

Justine Greening has said the Government’s response to the consultation will be published ‘in Spring’. So Fiona’s challenge remains!