Facts and figures about grammar schools

There are 163 grammar schools in England. Around 5% of secondary pupils in England attend a grammar school.

~19% of England’s secondary school pupils are affected by academic selection, attending either a selective school or a de facto secondary modern. (Based on 3458 secondary schools in England, 163 grammar schools, ~500 schools changed by grammar schools. 663 of 3458 schools = 19%)

Around 100,000 pupils sit the 11-plus each year.

There are 35 local authories containing one or more grammar schools.

11 local authorities are classed as ‘highly selective’ by the DfE, with this designation based on more than 25% of pupils attending grammar schools. The highly selective authorities are Bexley, Buckinghamshire, Kent, Lincolnshire, Medway, Slough, Southend-on-Sea, Sutton, Torbay, Trafford and Wirral.

DfE data shows non-selective schools in highly selective areas have the lowest attainment. In 2022/23 they had an average Attainment 8 score of 42.3, and Progress 8 of -0.16, which is statistically significantly below the national average.

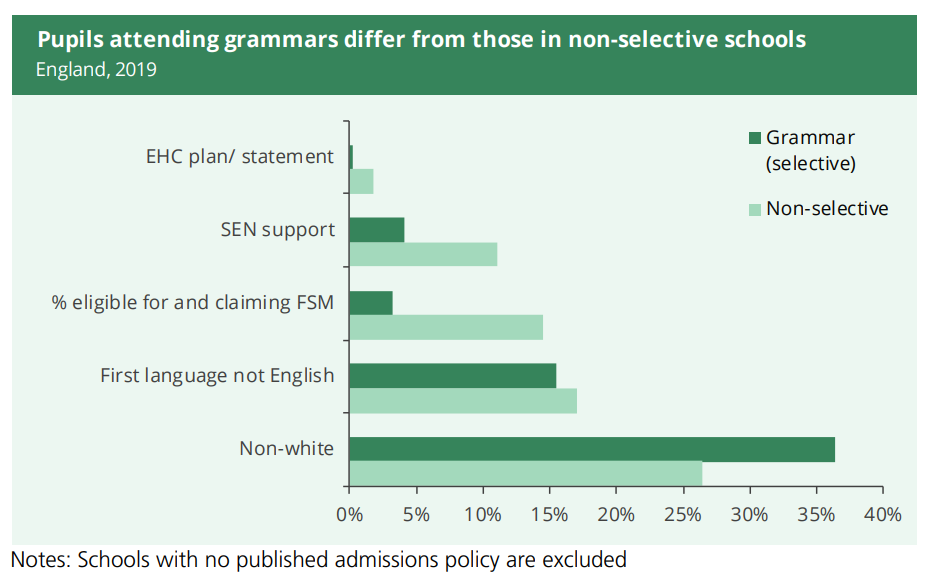

Free School Meals pupils are underrepresented in grammar schools, with just 6.7% of grammar school pupils taking free school meals, while the average in non-selective schools in selective areas is 28.4%.

Pupil Premium is an alternative measure of disadvantage based on eligibility for Free School Meals at any point in a pupil’s school life. Grammar school’s intake is made up of around 8.1% Pupil Premium pupils, compared to a national average of 27.1% disadvantaged pupils in secondary schools.

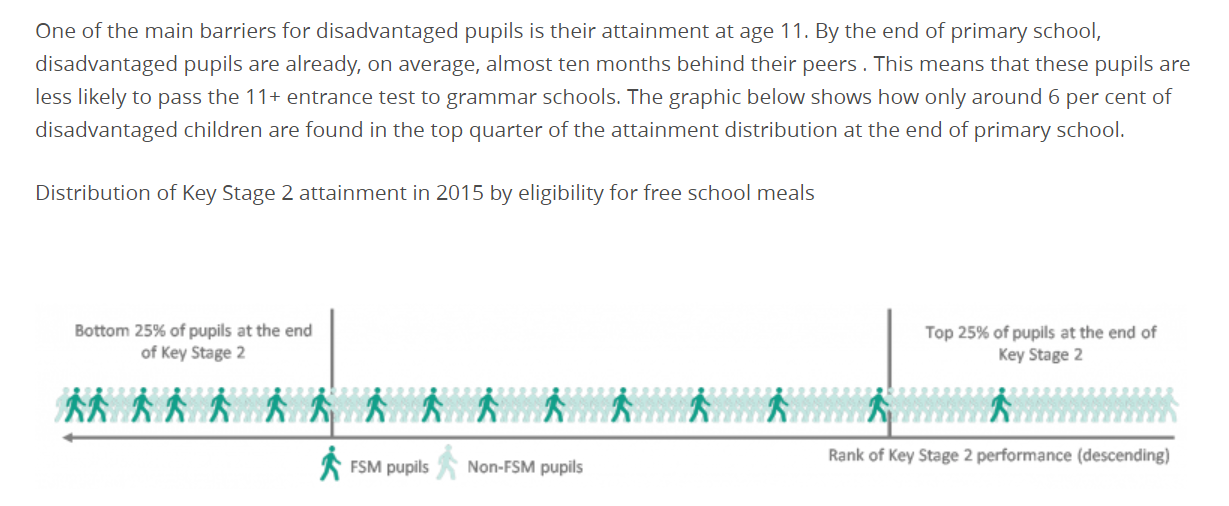

The reason grammar schools admit such low numbers of disadvantaged pupils is likely to be because these pupils are already significantly behind at school when the 11-plus exam is taken. Limited numbers of poorer pupils are likely to be in the top 20% or so ‘high attainer’ group that grammar school choose to select. An EPI study showed that only 6 per cent of pupils experiencing persistent disadvantage achieve the top 20% of GCSE scores, while overall 10 per cent of other disadvantaged pupils achieve this academic level.

Approximately 10% of grammar school pupils attended a fee-paying primary school before attending a selective secondary school. In England overall 5% of pupils attend private primary schools, so this suggests affluent families are deciding to send their children to grammar schools instead of fee paying secondary schools.

Grammar schools are far less likely to admit SEND pupils than non-selective schools, with just 0.3 per cent of statemented pupils in grammar schools (compared to 2 per cent in non-selective schools in selective areas) and 4.3 per cent of SEND pupils without statements (compared to 15.5 per cent at non-selective schools in selective areas).

Children in care are underrepresented in grammar schools. CF’s research showed 68 grammar schools contained no pupils who were flagged as Looked After Children. An average grammar school in a fully selective authority will educate just 2 looked after, or previously looked after pupils, while neighbouring non-selective schools will average 14 of these pupils.

Grammar schools appear to have a higher than average proportion of non-white pupils (36% compared to 26%) although there is relatively little difference in English as a first language by school type (16% compared to 17%).

Children who live in areas with grammar schools but don’t attend a grammar school tend to have worse outcomes. An FTT Education Datalab study showed educational outcomes for pupils attending non-selective schools in areas served by grammar schools tend to be lower than for similar pupils living in non-grammar areas. Although the percentage of pupils achieving five or more A*-C grades including GCSE English and maths was the same, the former group tend to do worse on higher-level outcomes. For instance, they were half as likely to achieve five A*-A grades at GCSE or attend a top third university.

Grammar schools poor record for admitting poorer pupils is exacerbated by the prevalence of paid-for 11-plus tuition. The EPI state, ‘It is difficult to identify precisely the extent to which it occurs, but survey and interview evidence provides an indication of its considerable scale. Polling conducted by Ipsos MORI on behalf of The Sutton Trust found that 18 per cent of young people aged 11-16 in England and Wales had received private tuition as part of preparation for a school entrance exam. Given that the 163 grammar schools in England are not spread evenly throughout the country, the proportion of candidates receiving tuition for grammar school entry is likely to be much higher than this: a smaller-scale survey carried out in Sevenoaks (in the fully selective local authority of Kent) found that 44.7 per cent of children entering the 11-plus had received private tuition before sitting the exam,’

Grammar school systems offer cause problems at post-16 level. Grammar schools tend to offer a good range of A levels and no vocational subjects, while nearby non-selective schools tend to have small sixth forms and a limited range of A levels. Kent County Council highlighted these problems in a report that stated, ‘Kent schools effectively continue to represent different systems (high school, grammar school) post 16, as they have done pre-16… Many pupils’ choice at 16+ is constrained by what their school offers, in terms of qualifications.’ It also states, ‘ The gap between progression rates to the most selective higher education institutions for disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged students appears to be wider in Kent than nationally. Overall, young people from disadvantaged backgrounds appear to make even less progress than their non-disadvantaged peers when the data for Kent is compared to the national average: this raises questions about their access to grammar schools.’

Comprehensive Future’s map of grammar schools in England shows data for every school. This gives the percentage of disadvantaged pupils, the percentage of pupils attending a grammar school who are likely to have come from a fee-paying ‘prep’ school, and the relative selectivity of every grammar school. View the map HERE.

A companion piece reviewing the evidence around the 11-plus and children’s mental wellbeing can be found HERE.

Research about grammar schools

There is no boost to results in grammar school areas, and higher attaining pupils do better in comprehensive areas

A large scale study reviewed GCSE results and found that higher attaining pupils living in grammar school areas were 10% less likely to achieve 5 or more A or A* grades than equivalent pupils in comprehensive areas. Overall the results in grammar school areas were neither better or worse than comprehensive areas. Read an article about the research HERE, and the full paper can be read HERE.

Pupil’s results are no better in grammar schools

Another study of more than 500,000 pupils in England by researchers at Durham University found that “results from grammar schools are no better than expected” once social stratification (such as poverty, ethnicity, language, special educational needs) is taken into account. Read an article summarising the results HERE and the full academic paper HERE.

Most grammar schools offer priority access for disadvantaged pupils, but proportions admitted are still low

The BBC researched grammar school’s attempts to admit more disadvantaged pupils, and found the majority do now offer priority admission for poorer pupils. In many cases the numbers admitted are still low. In a quarter of the 160 grammar schools studied, fewer than 5% of children were eligible for pupil premium support – which is linked to free school meals and used as a measure of disadvantage. Read more HERE.

There are no social and emotional gains, or attainment gains, by grammar school pupils

The Institute of Education (IoE) published a study which found that grammar school pupils “do not gain any advantage

over children who do not attend a grammar school by age 14.” The IoE assessed a range of social and emotional outcomes, including young people’s engagement and well-being at school, their aspirations for the future, in addition to educational attainment levels, to try to determine the benefits of attending a grammar school. Read more HERE.

Access to grammar schools is strongly graded by family background.

Children from the poorest families are substantially less likely to attain a place even when they have high academic achievement at age 11. Read more HERE.

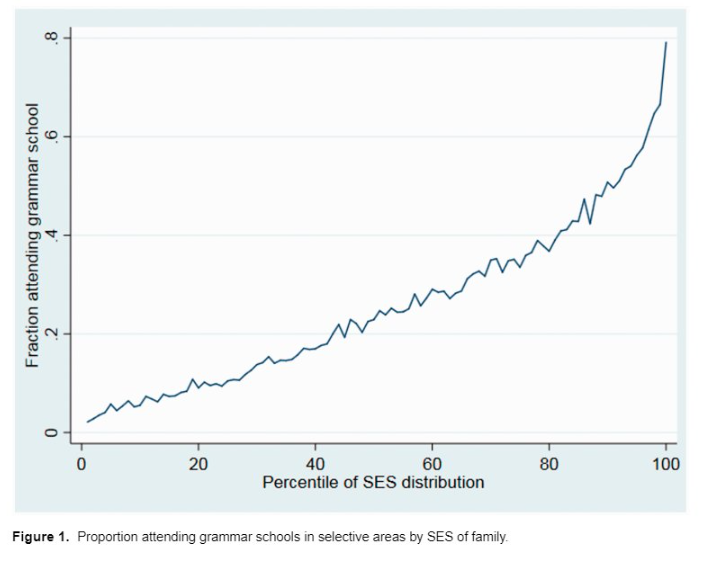

Grammar schools benefit the very affluent

Research for the UCL Social Research Institute, University College London found that access to grammar schools is highly skewed by a child’s socioeconomic status (SES) with the most deprived families living in grammar school areas standing only a 6% chance of attending a selective school. In contrast the most affluent families – the top 10% by SES – have a 50% or better chance of attending a grammar. While those pupils at the very top – the 1% most affluent – have an 80% chance of attending a grammar. Read an article summarising the research HERE or the full paper HERE.

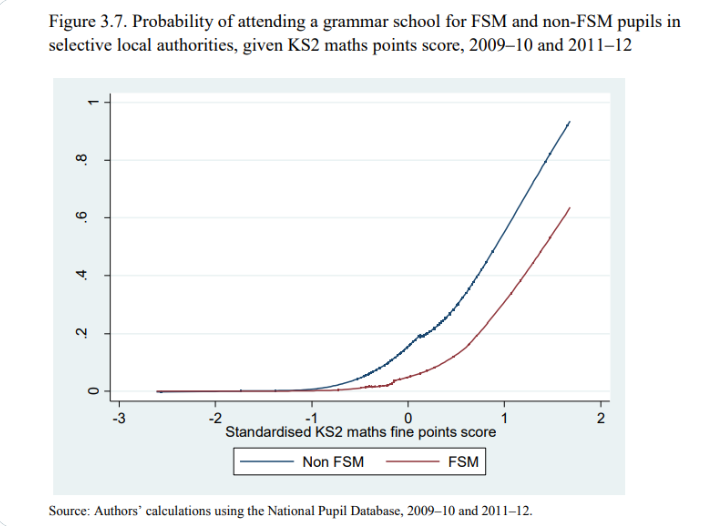

Wealthier pupils are more likely to pass the 11-plus, even when poorer pupils have the same attainment levels

Wealthy pupils are more likely to attend grammar schools than poorer free pupils, even when they have the same attainment levels (as judged by primary school SATs.) This is likely to be because wealthier parents are more likely to seek a grammar school education for their child, and because wealthier pupils are better prepared for the test through hiring a tutor or practising 11-plus papers. Read more HERE.

The probability of attending grammar school for Free School Meals pupils and more advantaged pupils, of the same attainment level.

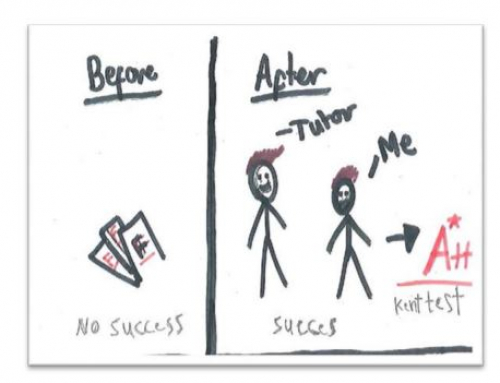

Paid-for tuition means wealthier children are more likely to win grammar school places

Research shows that high-income families are much more likely than low-income families to use private tutors to ‘coach’ their child for the grammar school entrance test. Less than 10% of children from families with below average incomes receive coaching for the grammar school entrance test. This compares to around 30% of children from households in the top quarter of family income. A study showed that around 70% of those who received tutoring got into a grammar school, compared to just 14% of those who did not. The huge impact of tutoring continues to hold even after a wide range of other factors (e.g. prior achievement, school application decisions) were taken into account. More HERE.

There is no overall attainment impact of grammar schools

The Education Policy Institute published a report on the impact of grammar schools on social mobility which stated that once prior attainment and pupil background is taken into consideration, there is no overall attainment impact of grammar

schools. The study found a very slight results boost for those attending grammar schools (0.3 grades per subject) and a small negative effect on those attending secondary modern style schools (0.6 grades lower per pupil) across GCSE subjects. The impact is greater for pupils eligible for free school meals who do not attend grammar schools as they achieve 1.2 grades lower on average across all GCSE subjects. Read an article summarising the research HERE, and read the full report HERE.

Grammar schools educate a low proportion of disadvantaged pupils and a high proportion of pupils who previously attended private schools

The Sutton Trust published research which stated that the relatively low proportion of grammar pupils eligible for FSM attending grammar schools cannot be explained by the location of the schools, or by differences in the prior attainment of disadvantaged pupils. At the other end of the scale, they claim grammar schools take a relatively large proportion of their pupils from independent primary schools. In 2016 the Sutton Trust estimated this rate at around 11%, nearly double the proportion of pupils aged 10 who attended independent schools that year. Read more HERE.

Grammar school tests select pupils from wealthier backgrounds

The Education Policy Institute (EPI) considered the likely impact of expensive 11-plus test tuition, and the problem of an attainment gap for disadvantaged pupils at age 11. The EPI concluded that test tuition is likely to boost the chances of pupils whose families can afford it, and grammar schools are a poor policy choice for improving outcomes for the poorest pupils. Read more HERE.

Academic selection depresses overall educational achievement and harms the chances of the poorest children the most

The Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) published a collection of essays exploring grammar school issues. The report highlights evidence that far from being a boost for social mobility grammar schools depress educational achievement in the areas where they are located. The report concludes by saying, ‘In a society that aspires to greater social equality and equality of opportunity there can be little justification for the continued existence of grammar schools today, let alone their expansion.’ Read more HERE.

The idea that grammar schools created social mobility in the past is a myth

There is an entrenched belief that because the post-war period led to huge social mobility, and grammar schools existed, selective education must have caused the social mobility. This is not true. A paper for the the IZA Institute of Labor Economics explored whether social mobility was boosted in local authorities that retained grammar schools when the rest of the country switched to comprehensive education. This paper states, ‘our report provides no support for the contention that the selective schooling system increased social mobility in England, whether considered in absolute or relative terms.’ Read an article about the research HERE and read the paper in full HERE.

Academic selection can affect the earning outcomes of children

The Social Mobility Commission published a report called, ‘The long shadow of deprivation: Differences in opportunities across England’ which looked at how the earnings outcomes of children from different backgrounds varies across local authorities, and this discovered that selection can be a factor. Thanet in selective Kent was highlighted as the area in the South East with the worst social mobility, with many other selective authorities showing large pay gaps between sons from disadvantaged backgrounds and their counterparts from more affluent families who grew up in the same area. The report says, “Areas with a higher proportion of grammar schools and more-segregated schools, have the largest educational achievement gaps. Sons from affluent families in these areas achieve much higher GCSE results than sons from deprived families in the same area.” Read an article about the study HERE and the full report HERE.

The wage distribution for individuals who grew up in selective schooling areas is substantially and significantly more unequal

A study found income inequality in selective areas. Those growing up in selective systems who make it to the top of the earnings distribution were found to be better off compared to their similar non-selective counterparts. However, looking at those at the bottom of the earnings distribution, those growing up in a selective system earn significantly less than their matched nonselective counterparts. Read more HERE.

Internationally the most successful education systems are comprehensive

A OECD PISA report, “Effective Policies, Successful Schools”, analysed schools and school systems and their relationship with education outcomes. The report warns of the dangers of sorting pupils into different educational pathways, pointing out that this can, ‘have unintended consequences, especially for socio-economically disadvantaged students, because sorting and grouping processes tend to be socio-economically, not just academically, selective.’ The report did find a small results boost within academically selective schools, but claimed the overall impact on school systems was negative. Read an article about the report HERE and the full report HERE.

11-plus tests are not very accurate

A study by the Sutton Trust revealed that 22% of pupils who sat an 11-plus were misallocated when their eventual GCSE results were considered. 11% of grammar school pupils obtained GCSE results that suggested they were a better fit for a secondary modern style school, while 11% of secondary modern pupils failed the test but their results suggested they deserved to be admitted to a grammar school. Read more about the reliability of the 11-plus HERE.

Grammar schools supposedly superior results are due to heritable characteristics involved in pupil admission

A study looked at differences in exam performance between pupils attending selective and non-selective schools and found that they mirror the genetic differences between the pupils. Although on average students attending selective schools outperform their non-selective counterparts in national exams these differences are not due to value added by the school, but instead due to the specific characteristics of pupils who attend grammar schools. Read more HERE.

Grammar schools are expanding even though there is a ban on new selective schools

In 1998 a law was passed forbidding the creation of new grammar schools and people suggest that as the pupil population expands this will force the existing 163 schools to become more selective. In fact grammar schools have kept pace with population growths, expanding on their existing sites and not becoming more selective. Since 2013/14 overall pupil numbers have grown by 13.43%. However, over the same period the number of children attending grammars in selective areas increased even further, by 14.91%. Read more HERE.

The government’s ‘Progress 8’ figures are biased towards grammar schools

Government league tables use the ‘Progress 8’ accountability measure to score the effectiveness of secondary schools in England. This measure is known to flatter grammar schools, and propel them to the top of league tables, while secondary modern style schools surrounding grammar schools do particularly poorly when judged by this measure. This means anyone looking at league tables will have an inflated idea of the ‘success’ of grammar schools, and it means grammar schools are not accountable for their results in the same way as other schools. It is likely to be one reason so many grammar schools are rated ‘Outstanding.’ It is believed that the high attaining pupils selected by grammar schools score particularly highly when measured by Progress 8, but there is little will to correct this flawed measure. Read more from Dr Thomas Perry HERE or from Education Datalab site HERE.

Do you know of any research about grammar schools and the 11-plus that we’ve missed? Get in touch and we’ll add it to this page.