We’ve been analysing our latest Freedom of Information request showing how many pupil premium pupils were admitted to grammar schools between 2017 – 2019. It would seem that that despite a drive by the Department of Education to widen access, there has been almost no change:

- The proportion of disadvantaged pupils (children classified as pupil premium) accessing grammar schools has actually fallen from 8.48% in 2017 to 8.31% in 2019 This is against a national average of 27.6% disadvantaged pupils in secondary schools.

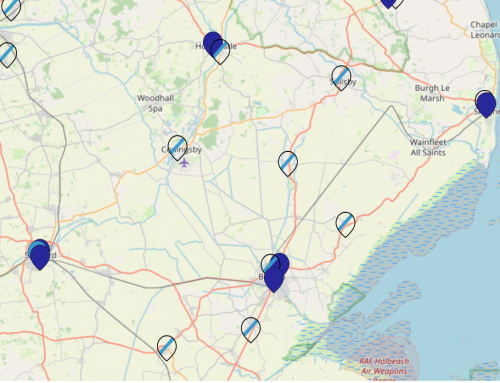

- The grammar schools showing the most improvement in their rates of access over the three-year period are: Chelmsford County High School For Girls (2% to 6.6%), Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School, Horncastle (3.3% to 10.5%) and Queen Mary’s Grammar School (7.3% to 24%.) In the case of Queen Mary’s Grammar School this was achieved by of the places to pupil premium pupils, regardless of where they lived, and ahead of all other applicants. It is a radical solution to boost access for poorer pupils, but may well mean many of these pupils are travelling a significant distance to school.

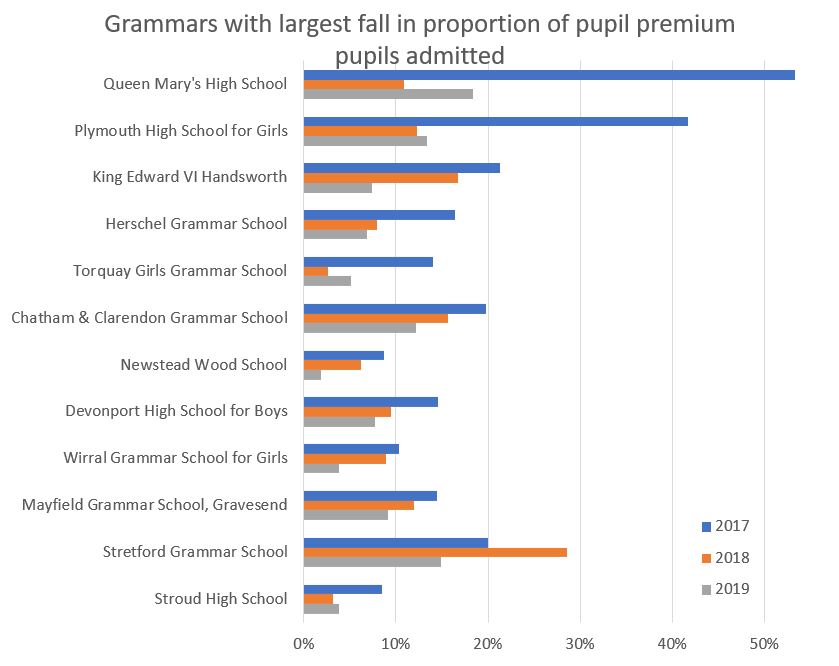

- Many grammar schools went ‘backwards’ (see graph), and actually admitted fewer pupil premium pupils in 2019 than in 2017.

- It is not clear why so many schools have seen their numbers fall, but we do know that the 11-plus test itself is the biggest barrier to entry for poorer pupils, who statistically speaking will have lower attainment. The grammar schools admitting high numbers of disadvantaged pupils appear to do so through lowering qualifying scores for disadvantaged pupils, or by offering less challenging 11-plus tests. Yet many selective schools refuse to adopt these methods. Schools in large selective authorities like Bucks or Kent, where all the pupils with an 11-plus pass will invariably be offered a grammar school place, often add ‘pupil premum priority’ to their admission policies. It seems these efforts are ineffective and tokenistic, the disadvantaged pupils who pass the test would all be offered places anyway.

- Most disappointingly, Kent County Council’s Select Committee, set up in 2016 to review ‘Grammar Schools and Social Mobility’, has made little impact in the county. Its 16 recommendations designed to improve rates of access to Kent grammars have failed to make a difference. Figures show that the position in Kent has remained stagnant over the last three years. Just over 9% of children attending Kent’s grammar schools are in receipt of pupil premium funding. This compares to 23% of Kent secondary school children as a whole.

Comprehensive Future’s Chair, Dr Nuala Burgess, said, “In spite of all the policies and promises to raise the numbers of disadvantaged kids in grammar schools, nothing is changing. It’s quite an indictment. It would be far better if Kent and all other selective counties stopped tinkering with selection and put their energy and tax payers’ money into creating better schools open to every child.

“It never ceases to amaze me that in spite of the wealth of academic research and evidence freely available, in 2020 we still have areas which think it is acceptable to segregate children socially and academically.”