It is hard not to see the government’s decision to re-open the debate about grammar schools as one more example of the bleak post-Brexit landscape.

It is hard not to see the government’s decision to re-open the debate about grammar schools as one more example of the bleak post-Brexit landscape.

Theresa May has made much of the opportunities that grammars offer to ‘ordinary working-class families.’ However, all the evidence points the other way as we know from looking at those parts of the country where selection never went away. Every year tens of thousands of children take the 11- plus exam and are officially declared either winners and losers before they have even finished primary school.

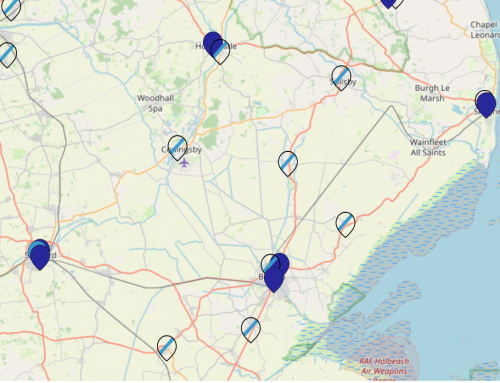

In fully selective areas like Kent and Buckinghamshire, grammar schools tend to educate the already advantaged and keep out children from poorer families and some ethnic minority backgrounds. On average only 3% of children in receipt of the Pupil Premium get into grammars. Selection then further exacerbates the attainment divide.

In contrast, successful comprehensive areas and systems, from London to Hampshire, show us what can be achieved when we concentrate on the right elements: excellent teaching, positive discipline, significant investment and proper support systems such as the hugely successful London Challenge.

More generally, comprehensive education has offered opportunities to millions of young people over the past fifty years with steadily rising attainment and far greater numbers going to university.

There has also been growing recognition across the political spectrum that non-selective education really can work, but instead of building on this growing consensus, May’s government is dragging us back to an already discredited and failed past.

The government knows it is on weak ground in terms of the evidence so watch out for some tricky new arguments. Pro-selection politicians and campaigners now insist it is not about division but diversity, increasing specialisation in a diverse schools market and the need simply to open up grammars to children from different backgrounds.

Don’t be fooled. It is about division. Every time you set up a selective school, even if you re-badge it a Centre of Excellence, it has a negative impact on the intake, results and overall mood of surrounding schools. And shouldn’t all our schools be encouraged to become Centres of Excellence?

As for opening up grammars to more children, which might mean lowering the bar on the entrance test, we might as well call this an all-ability school and drop the selective entrance tests altogether!

I urge all NUT members to respond to the Government’s green paper consultation (www.education.gov.uk/consultations) and make clear your rejection of these backward-looking ideas.

And please join Comprehensive Future (http://comprehensivefuture.org.uk) today. We need you in the months ahead.

Melissa Benn is a writer and campaigner and Chair of Comprehensive Future.

Article first appeared in The Teacher November 2016.