This review is reproduced with thanks from CASEnotes – www.campaignforstateeducation.org.uk

This review is reproduced with thanks from CASEnotes – www.campaignforstateeducation.org.uk

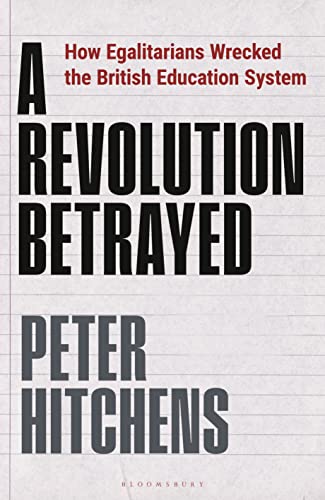

Book review: “A Revolution Betrayed: How Egalitarians Wrecked the British Education System” by Peter Hitchens

Bloomsbury Continuum – £20.00 (£14.37 at Amazon)

To anyone familiar with the weekly column written by Peter Hitchens for The Mail on Sunday this latest jeremiad will contain no surprises. All the familiar Hitchens tropes are there: rejection of the present in favour of an imagined pre-lapsarian past; the incontinent use of ridiculous hyperbole (Hitchens actually compares the “destruction” of the grammar schools to the Dissolution of the Monasteries and claims that in the golden past taking A-level examinations was equivalent to taking a degree); the assumption of the truth of what he purports (but completely fails) to demonstrate; the use of hostile generalisations and ad hominem attacks to dismiss those who disagree with him (“egalitarians”, “utopians” etc, driven by naïve beliefs and/or personal spite); an approach to evidence that is insouciant, to say the least, and that completely undermines his claim to be a defender of “standards”. It is not possible in a short review to deal with more than a few examples of the determinedly anti-intellectual and unscholarly approach favoured by Hitchens but the following is quite typical.

Early in the book (p.7) Hitchens asserts that the 163 selective grammar schools that have survived in England are no longer allowed to be the sort of schools that they once were (whatever that may mean). On page 18 he adds that these schools are utterly unlike the 1,300 such schools that flourished in the national system before 1965 because they are unfair in that they select by wealth…this is why they help the ancient universities to fulfil their state school quotas without doing too much damage to their quality. Hitchens produces no evidence that the “ancient universities” admit students from state schools in order to fulfil “quotas” or that state educated students at Oxbridge “damage” (albeit not “too much”) the “quality” of these institutions. There is, of course, no such evidence: admissions at Oxbridge are ultimately in the hands of the individual colleges and these vary considerably in the proportion of state educated students whom they admit.

As for “quality”, repeated research carried out by a range of organisations since 2010 has confirmed that students admitted to Oxbridge from comprehensive schools are more likely to obtain a top degree (1st or 2.i) than those admitted from grammar schools and that the latter, so far from not “doing too much damage” to overall standards, actually outperform the privately educated. None of this interests Hitchens, of course, because for him evidence is just an inconvenient nuisance that cannot even begin to compete with the emotional intensity of his convictions. Thus, whereas pupils from early post-war grammar schools were admitted to Oxbridge “on merit”, the much greater proportion of state educated pupils now admitted to these universities are there as a the result of political pressure exercised through imaginary “quotas”. That the latter justify their admission by obtaining better degrees than the privately educated is quietly ignored as it is not consistent with the premise of the book that the education system has been “wrecked”. If obliged to confront this inconvenient fact, Hitchens would probably argue, without evidence, that the degree examinations are in some way “biased” towards the state educated, thanks to the machinations of “egalitarians”.

On p.25 Hitchens states that the pre-1965 grammar schools admitted many pupils from poor homes. The only evidence offered in support of this claim is a reference on p.61 to the Gurney-Dixon Report of 1954, which records that 64.6% of grammar school pupils came from working class homes. In 1954 the terms “working class” and “poor” were not synonymous but, leaving that aside, Hitchens fails to explain that the reason for this report was the government’s concern that working class children who passed the 11+ and went to grammar school were not taking advantage of the opportunities offered to them – hence the report’s official title: “Early Leaving”.

Hitchens also fails to acknowledge that Sir Samuel Gurney-Dixon himself advises in his introduction to the report that its description of the social backgrounds of grammar school pupils should be treated with caution, being derived entirely from information supplied by the head teachers of the 10% sample of grammar schools on which the report is based.

Naturally, Hitchens largely ignores the Crowther Report of 1959, whose information was based upon much more comprehensive studies than those of Gurney-Dixon, including a detailed survey of all young men entering National Service between 1956 and 1958. In his conclusions, Crowther states flatly that “a majority of the sons of professional people go to selective schools but only a minority of manual workers’ sons do so” and he adds that “a non-manual worker’s son is nearly three times as likely to go to a selective school as a manual worker’s”.

Also largely ignored are the Robbins Report of 1962 and Jackson and Marsden’s qualitative sociological work of 1968, “Education and the Working Class.” Hitchens mentions these works in passing but fails to acknowledge, let alone deal with, their central ideas. In any case, Hitchens’s use of Gurney-Dixon fails on its own terms because, even if nearly 65% of their pupils had indeed come from working class homes, this would still have left working class children seriously under-represented in grammar schools as in 1954 they represented between 75% and 80% of the school population overall.

Also largely ignored are the Robbins Report of 1962 and Jackson and Marsden’s qualitative sociological work of 1968, “Education and the Working Class.” Hitchens mentions these works in passing but fails to acknowledge, let alone deal with, their central ideas. In any case, Hitchens’s use of Gurney-Dixon fails on its own terms because, even if nearly 65% of their pupils had indeed come from working class homes, this would still have left working class children seriously under-represented in grammar schools as in 1954 they represented between 75% and 80% of the school population overall.

However, Hitchens has already stated on p.25 that it was only to be expected that the children of the poor would be under-represented in grammar schools: Being based on merit, grammar schools…would obviously favour those classes in society that are ambitious and can only attain their aims through merit and hard work. Leaving aside the question of what actually constitutes “merit” in this context, this is exactly how the parents of modern grammar school pupils might describe themselves but to admit this would be to reject the basic, if unadmitted, premise of a book which, like most of its author’s writings, promotes the idea that the world has been going to hell in a handcart since the early 1950s. Hitchens was born in 1951 so cannot attest to this personally, of course, any more than he can offer any personal experience of grammar schools, having been educated entirely in private schools.

Not a book to be taken seriously by anyone who knows anything about the history of post-war education.

This review is reproduced with thanks from CASEnotes – www.campaignforstateeducation.org.uk

This review is reproduced with thanks from CASEnotes – www.campaignforstateeducation.org.uk Also largely ignored are the Robbins Report of 1962 and Jackson and Marsden’s qualitative sociological work of 1968, “Education and the Working Class.” Hitchens mentions these works in passing but fails to acknowledge, let alone deal with, their central ideas. In any case, Hitchens’s use of Gurney-

Also largely ignored are the Robbins Report of 1962 and Jackson and Marsden’s qualitative sociological work of 1968, “Education and the Working Class.” Hitchens mentions these works in passing but fails to acknowledge, let alone deal with, their central ideas. In any case, Hitchens’s use of Gurney-