Conference November 21st 2015

Selection the growing threat – a report

Part 1 – Selection the damage continues

Comprehensive Future supporters from selective areas described how selection affects children, schools and their communities.

Lincolnshire

Alan Gurbutt lives on the East coast of Lincolnshire. He has campaigned for an end to the 11-plus since 2007 and is a member of Comprehensive Future’s steering group.

I’m a parent and former school governor at a secondary modern school. I have lived for the past 13 years in a seaside town in the south part of Greater Lincolnshire on the east coast, between Grimsby and Skegness, the most deprived area within East Lindsey and also in England. In 2013 The Campaign to End Child Poverty noted our area suffered from 40% child poverty, yet we still select children at 11+ while mounting evidence shows living in poverty damages children’s brains, and, from deduction, their ability to pass school entrance tests.

From my perspective, with some small exceptions of about 3-6% of students in receipt of free school meals, the characteristics of parents whose children attend Lincolnshire grammar schools tend to represent professionals, those who can afford 11+ coaching, while children in our secondary modern schools tend to come from much poorer backgrounds, which is in sharp contrast to the intake of our primary schools, most of which provide comprehensive education for all children. I am not bashing schools, but in Lincolnshire we are stupid to divide children at 11+. This test segregates those in our community who have plenty from those who have little, destroying vital opportunities where there is poverty and indifference for social integration. This leads to mistrust. Henceforth, the very presence of a grammar school is enough to prevent the disenfranchised from speaking out against selection for fear of damaging their children’s chances.

Selective education doesn’t incentivise the better-off working in our public services to identify the socio-economic problems that are holding our children back in education. They too are held to account for government targets; new targets need more money, not cuts. But that’s not to say some don’t support grammar schools for their own children.

Failure and rejection at 11+ leads to isolation of the cruellest kind. Parents reach out to grammar schools held high as beacons of social mobility amid poverty, but in essence failure at 11+ states some children aren’t welcome into the so-called better selective schools. Nearby secondary modern schools are erroneously regarded as second-best. Nothing could be further from the truth, they have to deal with disappointed parents and deflated children coming into year 7 but they make huge strides of progress for our children. My daughter achieved some of the best GCSEs in the county at our local secondary modern school.

External to school, selection lowers the community’s expectations for children who attend our secondary modern schools. My children have experienced discrimination first-hand and it gets them down. It gets their friends down. Just recently a local authority maintained secondary modern school in our area has been earmarked for closure because 60% of parents have chosen to send their children elsewhere, which includes 16% going to grammar school. Not the usual 25% top ability cream-skim I know. Others come to grammar schools from out of catchment, but when considering 40% child poverty already impacts upon school performance it is hardly conducive to school improvement.

I won’t mention Ofsted’s new “coasting school” self-fulfilling prophecy of falling below 60% A*-C GCSEs where there is snobbery for selective education, or child poverty, or the grammar school arms race for the Pupil Premium in competition with sponsored academies. No, I won’t mention free market competition hurts children and schools – including grammar schools.

Post-16 education also presents a problem on the Lincolnshire coast. Grammar schools provide the nearest sixth forms for A-levels but if a pupil fails to get good GCSEs, given our isolated location, they are likely to face a considerable journey and costs to get to a college that might not provide suitable courses.

Issues with Lincolnshire’s home-school transport policy are exacerbated by selection. Transport is provided to schools within two Designated Transport Areas, one for free, non-means-tested transport, to grammar schools, the other for concessionary transport to non-selective schools, which is means-tested. To qualify for transport schools must be further than approximately 3 miles but not further than 6. If your child fails the 11+ and your catchment school happens to be “coasting” and you want to send them elsewhere, the chances are you will have to pay, even if your school of choice is located next to your nearest grammar school.

But it’s all change at grammar school at post-16. Better-off students leave if they don’t get the grades to stay on at sixth form, but they can often afford private vehicles to drive to college; meanwhile poorer students have to make do with concessions colleges are able to offer.

In summary, I very much refuse to be indifferent to Lincolnshire’s education system that helps one child at the expense of another while damaging communities and schools. I would like to think that the powers that be don’t understand the harm selective education is causing to our coastal communities, that one day we may be able to persuade them to make amends by ending the 11+.

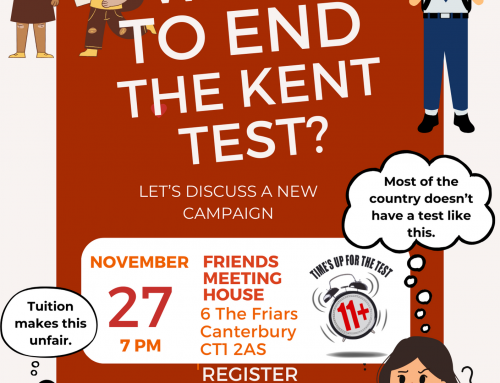

Kent

Joanne Bartley is a marketing manager and online education campaigner from Whitstable, Kent. Joanne regularly writes blogs and engages in social media debate in an attempt to show the pro-grammar lobby that selective education isn’t working in Kent

When my daughter failed her eleven plus I was shocked – this wasn’t supposed to happen to people like me! We shop at John Lewis, we eat at Pizza Express, we have books at home… And I take the children to museums and art galleries! When I picked up my daughter I would sometimes look at the other school run mums. I could guess, based on clothing, accent, and attitude, which parents would have a child who went to a good school, and which parents would have a child who went to a bad school.

You shouldn’t be able to look around a playground of ten year olds and predict the educational future of a child. But in Kent you can.

I don’t like to look at the world this way, but this is the way I’ve started to think and it’s horrible. And grammar Schools are great, aren’t they? Outstanding, aspirational places. I shouldn’t wish them away. But what of our non-selective schools? If we have grammar schools we must have these ‘other’ schools. They’re not comprehensives because they’re missing high ability kids. You can’t call them secondary moderns – people don’t like the name. They don’t really have a name, so we don’t talk about them. No one wants to talk about them anyway.

So, I’m a middle class mum, with a daughter who failed her Kent Test. I was looking forward to my lovely choice of five local schools, including three outstanding grammar schools. Instead I had the choice of two local schools, both with bad reputations. With an 11 plus you have lots of choice, good grammars, and good comprehensives too. If you fail then your choice of good schools can be improved if you live in a good area or go to church. But if you fail the Kent Test and don’t live in a good area you’re in trouble. If you’re poor or don’t make much effort with education it’s likely your child will go to a bad school.

If you look at the Ofsted ratings of Kent grammar schools you can see the difference in opportunities. If you pass the 11 plus there’s a 97% chance of a good or outstanding school. If you fail the 11 plus there’s a 24% chance of a requires improvement or inadequate school. Only 3 Kent secondary moderns are Outstanding, compared to 26 grammar schools. A quarter of children who fail the eleven plus will get a bad school. I don’t want to close good schools… Closing good schools doesn’t make bad schools any better… but something isn’t right.

Supporters of grammar schools often talk of their noble ambition of rescuing bright poor kids… But it’s a flawed plan. Why do they even aspire to an education system that helps disadvantaged children that are bright? Why don’t they want an education system that helps disadvantaged children full stop?

And we all know it doesn’t even work. We’ve seen these stats before… In Kent only 5% of children in grammar schools have received free school meals in the last 6 years. And it’s 26% in secondary moderns.

I fear the education divide in counties like Kent will only get worse. Our government is pressing for academic success with a focus on results. Non-selective schools struggle to meet academic goals, of course the nature of their pupils makes this hard. So they will sink deeper into trouble. The children under perform and the schools become slaves to the league table.

If we really cared about our secondary moderns they would be thriving, vibrant places that engage their children. Instead many suffer from disruption, a lack of aspiration, and unmotivated kids. It’s hardly surprising, we tell these children they’re not academic and give them nothing except academic targets anyway.

Ofsted’s Chief Statistician looked at the stats for secondary modern schools.

He said these school’s bad ratings were to be expected. He said any school with a profile of disadvantaged children was likely be a failing school. But he explained that schools with low attainers had to be judged against the same criteria as grammar schools. Otherwise we’re entrenching low expectations.

I do understand the idea of setting the bar high. It just feels sad watching schools, and children, jumping to reach that bar, knowing it will rarely be reached. Some statistics illustrate the situation

Kent & Medway Grammar school Ofsted ratings

Outstanding 68.4%

Good 28.9%

Requires improvement 2.6%

Kent & Medway secondary modern school Ofsted ratings

Outstanding- 3.8%

Good 71.8%

Requires improvement 21.8%

Inadequate 2.6%

Only 5.05% percentage of pupils in grammars were eligible for fsm at any time in last 6 years, in secondary moderns it is 25.8%

My daughter’s eleven plus saga continues… She now needs to move schools to find a decent sixth form. We visit grammar schools and they are amazing places. It’s not the results that impress me. I am staggered by the extra care that goes into enrichment days, the clubs the children set up themselves, the way children are encouraged to have outside interests, and learn independently. They also hear from inspirational speakers who talk about careers and achievements. These children are taught to have aspirations and succeed.

Secondary modern schools need this attitude more than any other kind of school. If we decide children can’t succeed in exams we should give them something else to be proud of. But sadly teachers in Kent comprehensives have no time, they spend their energy pushing children to meet exam targets. The children don’t set up clubs, they are glad to head home, they don’t like school.

There is no easy solution. But I will work with my local school to encourage improvements. This school may never excel on a league table, but it might excel in all the things parents might wish were on an Ofsted report instead. Those things that matter as much as exams.And of course we have a new threat arising from Kent… the annex.

We don’t yet know what it will mean, but we worry. And we have a new group in Kent keen to seek solutions to the problems. We are prepared to speak up and tell people Kent’s education system doesn’t work. Kent country council set up a committee to review social mobility in grammar schools. They admit there is a problem, and I hope they will try to fix it. But I want them to look at the problems of the other, nameless, never talked about schools…. We need to give all children an excellent education not only those who pass the Kent Test.

Despite the disappointment of eleven plus failure my daughter has turned out fine, she wants to study Computer Science at university. I think the ‘right’ kind of parents will always nurture children to succeed. But perhaps this is more reason to look out for the children who don’t get that kind of help. Do we help these children by making more grammar schools? Of course not. We need to make education work for the children whose opportunities are limited by a bad test result and then a bad school. Now my son has an eleven plus coming up. I look around the playground and I worry more about the divided paths to bad schools and good. I know that all Kent’s children deserve the opportunity of a great education.

Buckinghamshire

Rebecca Hickman worked in government relations for Save the Children and the Mayor of London, before moving into development work in South Africa. She currently undertakes a wide range of consultancy work, as well as research and writing, specialising in education and the not-for-profit sector. and

Katy Simmons is a long-term Chair of Governors at a Buckinghamshire secondary modern school A former lecturer at the OU, she writes about justice and equality, focusing particularly on children of BME heritage

Background

1. Buckinghamshire is a fully selective LA, with 13 grammar schools and 21 secondary modern schools. All the grammar schools are described by OFSTED as ‘outstanding’ or ‘good’. Over half the secondary moderns are described as ‘requires improvement’ or ‘requiring special measures’.

2. Although educational attainment overall exceeds the national average, BCC also has ‘one of the widest gaps in achievement between economically underprivileged pupils and the average’.

3. Disadvantaged children and children of Black and Minority Ethnic heritage are disproportionately allocated to secondary modern schools, effectively segregating communities.

4. A ‘new’ 11+ test was introduced in 2013 with claims that it would be ‘fairer’ and more resistant to coaching. For two years, using Freedom of Information requests, we have secured data on the outcomes of the new tests. The Local Authority, the test provider (Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring, Durham University) and the Buckinghamshire Grammar Schools have been very reluctant to give us information.

5. We have published our findings in a report called ‘Who Benefits?’ The most recently updated version of this is available on the Comprehensive Future website.

6. In summary, the evidence suggests that the new 11+ exam has made no difference in addressing the following trends in Bucks, and indeed shows that some trends are getting worse:

Our findings

• The main issue is the huge detriment suffered by all children in a selective system as a result of the enforced segregation – but in particular by the vast majority of children who end up at secondary moderns. However, the introduction of the so-called ‘tutor proof’ test in Bucks gave us an opportunity on two levels. First, it showed that the system’s chief apologists are concerned about the credibility of the 11+ exam and whether or not it fairly selects according to innate ability rather than prior education – so they themselves were helping to highlight this major flaw in the system. Secondly, it would give us an unprecedented opportunity to collect data on the futility of trying to make any exam resistant to coaching. And by putting this in the public domain we could help to kick away one pillar of the system, AND at the same time highlight the degree to which children from certain backgrounds are systematically discriminated against through the testing process. We looked at –

• What might we have expected to see if the test had become more resistant to coaching:

• improved pass rates for state school children

• lower pass rates for private school children

• higher pass rates for children on Free School Meals

• more even results across all racial groups

• more even results between areas with different socio-economic profiles

So what do our three year’s worth of data show has happened?

Declining pass rates for Bucks state school pupils

• Children attending state primary schools continue to perform worse than other children in the 11+ exam. Overall, one in three children passed the 11+ exam in 2015. But of children at Bucks state schools, only one in five passed (under the old exam closer to one in four).

• If the pass rate was standardised to ensure that one in three Bucks state school pupils passed the 11+ (i.e. the overall average pass rate), a staggering 600 more children at Bucks state schools would have passed in 2015.

• If you look at the gap between the overall pass rate and the pass rate for state school pupils, it has increased. In the last year of the old exam the gap was -9 percentage points – in other words overall 32% of children passed, but only 23% of state school pupils passed. In the first year of the new exam, the gap grew to 10 percentage points, and in the second and third years to 12 percentage points.

Increasing pass rates for children at private schools

• Private school children had much higher pass rates than state school pupils under the old exam. This remained about the same in the first two years of the new exam. But increased this year. The private school pass rate now stands at 60% – in 2012 it was 56%. This means that a child from a Bucks private school is now nearly three times more likely to pass the 11+ exam than a child from a Bucks state primary school.

• Looking at the gap again…. In 2012 the gap between state and private school children was 32 percentage points. In 2016 the gap is now 38 percentage points.

Much lower pass rates for children on Free School Meals

• We know that the 11+ pass rate for children on FSM is shocking. In Bucks, we don’t have the pre-2014 data so we can’t compare the situation before and after the new exam. However, we do have the data for the first year of the new exam and we can see how dire the situation still is.

• In 2014, children receiving free school meals (FSM) had an extremely low pass rate, of only 4%. To put that into context, the Royal Grammar School and Highcrest Academy (non-grammar) are about one mile apart. In their 2014 intake, the RGS had 4 children on FSM, while Highcrest has 49 children on FSM.

• We have tried to get the FSM data for 2015 and 2016, but were told last week by the grammar schools that they have stopped collecting it.

Much lower pass rates for children from certain ethnic backgrounds

• In the first two years of the new exam, the pass rate for Pakistani children (who are the largest ethnic minority group in Bucks) was about half the pass rate of all Bucks state school pupils. Only 9% of these children passed in the first year and 11% in the second year – this is a gap of 20 percentage points when compared with the overall pass rate.

• Black Caribbean and Mixed White-Black Caribbean children are also doing particularly badly.

• Again, in terms of how this plays out in the profile of our local schools. John Hampden Grammar School is only one mile away from Cressex Community School (a non-grammar). In 2014, 65% of Cressex’s intake was of Pakistani heritage, compared to only 4% of John Hampden Grammar School’s intake.

Large gap between the pass rates of the poorer and wealthier areas of Bucks

• There has continued to be a considerable difference in the pass rates for children from different Bucks districts. In all three years, a child from Chiltern District was at least twice as likely to pass the exam than a child from Aylesbury Vale District.

In summary

• So not a single one of the key metrics that would indicate fairer outcomes for children has gone in the right direction.

• The new exam has been singularly unsuccessful in reducing the large achievement gap between children from different backgrounds. If anything the new exam seems to be conferring even more of an advantage on children from certain backgrounds – which would suggest it is even more coachable than the previous exam, or that more middle-class parents are investing in coaching than ever before.

• The credibility of the system turns on the test’s ability to accurately and fairly identify more able children. Our data not only shows it does not, it also would indicate that it cannot – not even with the best efforts of the so-called market leader in test development.

• Instead it discriminates according to social background, schooling and prior opportunity, meaning that our grammar schools bear less and less resemblance to the communities they are supposed to serve. The net effect is that existing patterns of disadvantage are not only reproduced but also reinforced. In fact, it is like taking every social and educational inequality that has emerged in the first ten year’s of a child’s life and they saying, ‘Right, let’s institutionalise that through a parallel schooling system’.

• So this data clearly gives the lie to the claim that grammar schools are a route out of poverty. How can they be an engine for social mobility when they systematically shut out children from disadvantaged backgrounds?

Birmingham

Maggie Le Mare is a mum with direct experience of Birmingham state education. She has seen the way the selection process affects her daughter, and her friends’ children. She has witnessed at first hand, the impact of the grammar versus comprehensive division.

Locally I am probably known as the one who bangs on about Fair Trade, Sustainability and Grammar Schools. My interest in this subject stems from my own education at a private, boarding school. When I emerged from that isolated, sheltered environment into the big, wide world I didn’t really know what had hit me!

We need to be able to rub along with everyone in society so when my daughter (who didn’t take the 11+) started secondary school I wanted her to learn this vital social skill from the start. She is 19 now and appears to be a much more grounded individual than I remember being at that age!

I’ll start off giving you a bit of background before telling what really bothers me about it. Birmingham has a population of 1.1 million. It’s a really good place to live: It is ethnically very diverse; it is very friendly; there’s plenty to do and loads of activities for children.

BUT – it has a grammar school system. There are 76 non-selective secondary schools.

There are 8 grammar schools. 5 of them are supported by the wealthy King Edward VI Foundation – one of the real ironies here is that King Edward VI set up the Foundation over 400 years ago to bring education to those who could not otherwise afford it. The KE VI Foundation sponsors only 1 academy school in the entire city [in Sheldon Heath]

Most children start their school lives in their local state primary. In areas where parents are more affluent or ambitious or both – they want their children to go to grammar schools. Preparation (by which I mean tutoring) for the entrance exams can start as young as Years 3 or 4. Shockingly, to me at least, some tutors won’t accept children if he or she feels that they won’t pass the entrance exam: after all, the tutor doesn’t want to be seen to be failing either. It’s not a cheap exercise: the cost of tutoring is between £30 and £50 per hour, usually for weekly sessions. After several years of tuition pressure on children can ramp up the closer it gets to the exam

You hear some pretty amazing stories – like this one: Families taking tutors on holiday with them or families not going on holiday so that tuition or revision can go on throughout the summer.

Ask parents what they think of Birmingham’s education system and they tell you it’s divisive and unfair. In what ways is it divisive? The obvious ones are to do with friendship groups, parents and communities. The more insidious ones are to do with the division of abilities, resources and opportunities.

So – first – it divides friendship groups. After year 6 – children will be divided between schools all over the city – breaking up friendship groups that they have developed over the previous 7 years. Because their schools are so spread out, getting to school often involves long bus, train or car journeys

Secondly – it divides parents. Strong opinions and disagreements are heard in the playground sometimes threatening friendships. Comparisons with and competition between families can be very destructive

Thirdly, it divides communities. When students are no longer at a local school many of their activities will happen in other parts of the city. Their friends can live miles apart from each other – sometimes outside Birmingham. Parents end up ferrying their children all over the place. This has an impact on: children’s social and academic lives; parents’ stress levels and relationships; the environment; traffic and family finances

By comparison if students attended local schools the local community would be strengthened in terms of networks, activities and social cohesion. Their friends would be local, often living within walking distance. Several of our friends felt so strongly about it that they moved out of Birmingham to avoid the selective system. Many students at comprehensive schools compare their school with the KE VI schools that have wonderful facilities with concert halls, theatres, large playing fields, dance studios and gyms. Many comprehensives are in dire need of refurbishment or rebuilding. One of our local schools has trouble getting adequate gas and water supplies into their science labs.

It is an elitist system.

Despite claims to the contrary social mobility is not improved with the grammar school system: the vast majority of parents have to be able to afford tuition. One of the best indicators of deprivation is Free School Meal take up. In grammar schools it is about 3% In comprehensives it is anything from 25% – 70% or above.

The effect on non selective schools.

90% of students applying for a grammar school place are not accepted. A minority of these will go to private schools, the rest to comprehensives. They can arrive at their comprehensive secondary school feeling that both they and the school are second best. This isn’t good for confidence or self-esteem. Or – they’ve been told that they are too good for that school and they arrive believing they are a cut above the rest. This doesn’t go down well with either the students or the staff. It can result in some challenging behaviour from the start of year 7 – with teachers having to manage that. Schools benefit from a mix of students in terms of ability, faith and social groups. Non-selective schools in Birmingham miss out on many of the top-end ability students.

Another difference is parental involvement.

Grammar schools tend to have more educated, ambitious and motivated parents who run PTAs or friends associations. In my experience it is very difficult to get parents involved at comprehensive schools. A teacher recently said to me that the poorer the school the more a school needs exactly those sorts of parents: the more educated, ambitious and articulate ones.

Expansion of grammar schools

All the grammar schools expanded this year taking in an extra year group. To ensure all places are filled they adjust their entry requirements, putting pressure on the non-selective schools. One built a new 6th form centre funded by “former pupils, parents and generous grants from the KEVI Foundation”. At my daughter’s school, on the other hand, years have been spent bidding for funding, using already scant resources, for much needed 6th form facilities and a new gym. Grammar schools poach students for their 6th forms from non-selective schools. No wonder either! The comprehensive students joining the grammar schools for 6th form often out-perform the grammar school students i.e. those who have been at the grammar school since year 7.

To sum up – it’s a fragmented and divisive system. Affecting –

• Friendships and relationships

• Family finances

• Communities

• Academic performance

• Social interaction

• Cultural and social understanding

• Traffic and the environment

• Ambitions and aspirations

• Opportunity causing a disparity of facilities and resources that has an insidiously detrimental effect on children in Birmingham.

Of course, the situation is compounded if you have more than one child and the whole rigmarole is repeated.

Points from discussion

• Buckinghamshire may be unique in that all primary children do the Bucks test.

• A non selective school in Bucks introduced banding. It has had the expected effect ie some children living close from the bottom band have not got places. It is particularly unfair to introduce banding in a selective area.

• Should we use Ofsted findings to judge schools anyway?

• A Bucks resident has been trying to get more information about the nature of the test. So far without success.

• It is possible that proposals for further annexes on the Sevenoaks model will meet parental opposition. There have been no other parental petitions for grammar schools.

• One reason that there is not the upsurge in opposition to selection which there was in the 60s is that those most disadvantaged by it are the least powerful.

• There is an opportunity now to lobby the Labour party to make a commitment to end selection as party policy.

• The view that grammars do best for able students must be tackled. In fact comparisons in both Kent and Bournemouth by headteachers of non selective schools had found that their able students had made more progress than those of similar attainment at grammar schools.

• A cross party consensus is needed. Evidence that the local consensus is breaking up is helpful.