A new paper published in the British Educational Research Association (BERA) Review of Education, highlights the limited use of evidence in parliamentary debates about selective education. The paper states, ‘during debates on policy a number of rhetorical tools are used, including anecdote, reliance on party platforms, ad hominem-style attacks on the opposing party and a simple lack of response to evidence when it is raised.’

A new paper published in the British Educational Research Association (BERA) Review of Education, highlights the limited use of evidence in parliamentary debates about selective education. The paper states, ‘during debates on policy a number of rhetorical tools are used, including anecdote, reliance on party platforms, ad hominem-style attacks on the opposing party and a simple lack of response to evidence when it is raised.’

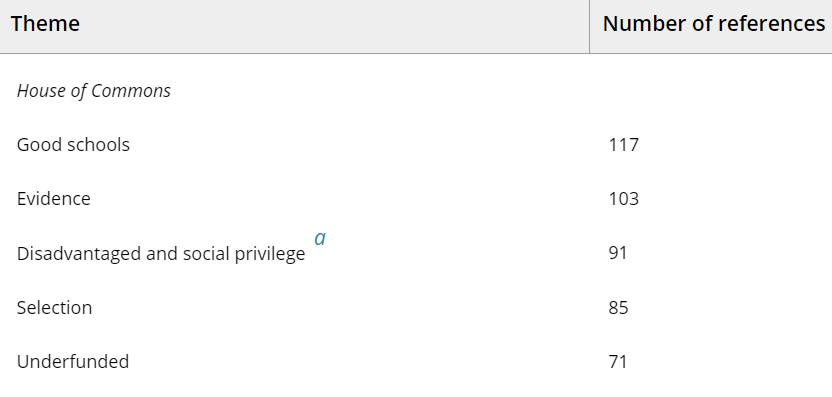

The researchers studied 11 parliamentary debates about grammar schools and used software to analyse the themes of the debates. The study identified the top theme in the House of Common’s debates about grammar schools was that these are ‘good schools.’

The software showed that the phrase ‘good’ connected to grammar schools was mostly used by MPs from the Conservative party, and in debates calling for evidence, the response was frequently that, ‘grammar schools are good schools.’

The report authors suggested there could be a subtle moral assertation being made about ‘good’ and ‘bad’ schools in the use of this language. If we are to believe that MPs are using evidence of the school’s Ofsted judgements it is a fact that 82% of grammar schools are rated ‘Outstanding’ by Ofsted. Yet, it is interesting to note that MPs did not choose to use the word ‘outstanding,’ which is rooted in evidence (if only from Ofsted’s reports) instead, the MPs invariably picked the phrase ‘good’ which has a moral meaning.

The parliamentary debates were predominantly discussing the £50 million a year Selective School Expansion Fund, with opposition MPs challenging evidence of any need to expand grammar schools, and regularly hearing ‘evidence’ that they were “good schools.” The report author’s suggestion was that this was a ‘moral sidestep,’ with any discussion of grammar school problems avoided by simply asserting a need for ‘good school places.’

As the paper playfully points out, if MPs wanted to apply the logic of rewarding and allowing ‘good’ schools to expand, then the implications would lead to ‘good’ English schools receiving an extra £8 billion in funding!

As the paper explains, ‘We first assume that if divided equally between each of the 159 ‘good grammars’ (this includes Ofsted rankings of Good and Outstanding—Full Fact, 2016) the £50 million SSEF would provide £314,465 extra funding per school. If the logic of allowing good schools to expand, simply in relation to Ofsted rankings—after all, this is the government evidenced standard—were applied to all good schools, then this would correspond to:

- The 2850 good and outstanding comprehensive schools it could be expected that £896,226,415 (2850 × £314,465) would be budgeted for their expansion.

- 91% of the 20,925 primary schools (19,041 schools) are rated good and outstanding. Therefore, they would receive £6,580,188,679—over £6 billion.

- And the 2915 good and outstanding nurseries would receive £916,665,475.

Therefore, the total expansion budget for all good schools would be £8,393,080,569.’

This extrapolation of MPs logic does make a very good point. There was clearly limited evidence of any real need to expand grammar schools, and also a great deal of evidence of the many problems with academic selection, which was roundly ignored. The paper sums up the problem. ‘Our research has discovered that the dominant discourse of good schools has led to an evasive moral sidestep, but also the discursive fantasy world of the ‘good school’, where one particular type of school is disproportionally perceived and presented as good.’

This paper was authored by Dr Alan Bainbridge, Tom Troppe and CF’s Jo Bartley, and contains some interesting insights into MPs use of evidence when making policy. It can be read in full HERE.