A memorandum of understanding between the Grammar School Heads Association (GSHA) and the DfE has been in place between 2018 and 2022, seeking to increase the number of pupils from poorer backgrounds admitted to grammar school. The DfE has recently reviewed the progress of the plan, and found that the increase in disadvantaged pupil numbers is less than a percentage point. They explain that between 2017/18 and 2021/22 there has been a slight increase overall in the percentage of disadvantaged pupils on roll in grammar schools; rising from 7.2% to 7.9%.

A memorandum of understanding between the Grammar School Heads Association (GSHA) and the DfE has been in place between 2018 and 2022, seeking to increase the number of pupils from poorer backgrounds admitted to grammar school. The DfE has recently reviewed the progress of the plan, and found that the increase in disadvantaged pupil numbers is less than a percentage point. They explain that between 2017/18 and 2021/22 there has been a slight increase overall in the percentage of disadvantaged pupils on roll in grammar schools; rising from 7.2% to 7.9%.

CF’s Chair, Dr Nuala Burgess, told Schools Week, “A rise of 07% in just four years is a shocking figure. Grammar school heads should be ashamed. They make a very big deal about their schools being a force for social mobility. They are nothing of the sort. It looks like business as usual for grammar schools.”

The DfE report explains that many grammar schools have changed their admission policies to prioritise disadvantaged pupils. In 2017, of the 163 grammar schools, 63 offered a level of priority to disadvantaged children

within their admission arrangements. In 2022 this had risen to 136. However just 25 grammar schools lower the test pass mark for disadvantaged children.

There are three key reasons why grammar schools changing admission policy makes minimal difference to the numbers of disadvantaged pupils accessing the schools.

Grammar schools generally admit the top 25% high achieving pupils, but due to the attainment gap, most poorer pupils do not reach this attainment level. A report by the Sutton Trust found that only 15% of disadvantaged pupils were in the top 25% for attainment. This means that the main barrier to entry for disadvantaged pupils is achieving a pass in the 11-plus test. Simply tinkering with admission policies, without lowering the score needed in the test, will not significantly increase disadvantaged pupil number in grammar schools.

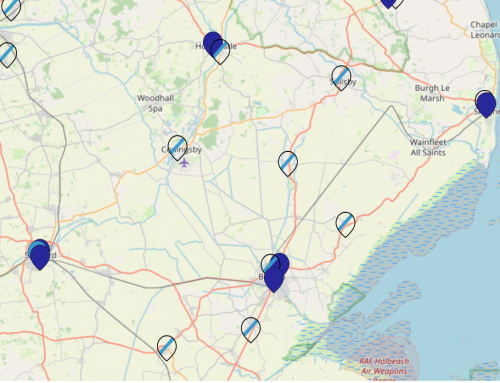

Another issue is that in most selective areas, including Kent (32 grammar schools), Buckinghamshire (13 grammars) and Lincolnshire (15 grammars) the 11-plus test system is designed so that there will be enough grammar places for all local pupils who pass the test. This means that grammar schools in these areas that add an admission ‘priority’ for disadvantaged pupils are making a meaningless gesture, because all the local disadvantaged pupils who pass the test will achieve a place through regular admission.

It is also the case that research has shown that parents from disadvantaged backgrounds often associate grammar schools with ‘tradition, middle class values and elitism’ which creates a social rather than educational barrier to entry. They simply do not see the ‘benefits’ of selective schools. Grammar schools might do their very best to suggest they are not traditional schools full of middle class pupils, but the fact is most of the schools are exactly like this. Grammar schools open days are more likely to showcase pupils who are classical musicians and opportunities for trips abroad, while high schools are more likely to show off contemporary dance and affordable school trips. Parents are smart enough to see that pupils sit exactly the same GCSE in both grammars and non-selective schools, and what exactly are the benefits of a grammar education if results mostly reflect the pupils they select? So why shouldn’t poorer parents shun the stress of a judgemental 11-plus test, and simply apply for a local non-selective school?

The GSHA memorandum has been renewed in 2023 and the schools will continue to make efforts to boost entry for poorer pupils, but they face some serious challenges in achieving this. There are systemic problems with selective education that mean these schools can not admit as many disadvantaged pupils as inclusive comprehensive schools.

The DfE conclusion of the report is not a glowing endorsement of the work so far. It says, ‘While there has been a small increase overall, there is lots of variation between schools. Some have seen very significant increases, others have seen a decline and some have seen no substantial change…

‘The number of disadvantaged children in grammar schools generally remains low. The fact that the number of disadvantaged children at grammar schools remains low in the face of interventions to increase their numbers shows what a complex issue this is to resolve. Many grammar schools are committed to admitting children from all backgrounds, but to achieve this is likely to require multiple interventions. All schools, especially those which have made no progress or very little progress in admitting greater numbers of disadvantaged children, need to challenge themselves to do more.’