What does research tell us about selection? It tells us a great deal, and almost none of it is helpful to the Government’s plans to expand selection in England. One of the unexpected results of the Government’s consultation document, Schools That Work for Everyone, published in 2016, was that a lot of academic organisations started to do research into a subject that they would not have looked at if the Conservatives had not put it firmly back on the agenda.

What does research tell us about selection? It tells us a great deal, and almost none of it is helpful to the Government’s plans to expand selection in England. One of the unexpected results of the Government’s consultation document, Schools That Work for Everyone, published in 2016, was that a lot of academic organisations started to do research into a subject that they would not have looked at if the Conservatives had not put it firmly back on the agenda.

One research study after another has shown that comprehensive education gets better results for society than selection. In the press release that announced the additional funding for grammar schools, the Government claimed that “research shows pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds attain better results in selective schools and around 60% of these schools already prioritise these children in their admissions.” The research was not cited and the claim that 60% of selective schools already prioritise the admission of children from disadvantaged children was misleading.

The “research” showing pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds attain better results in selective schools may come from a Department for Education (DfE) statistical first release which did not contain any research. As its name suggests, it reported statictics. This showed outcomes for children on free school meals getting slightly better results in grammar schools, but there are two important caveats. Firstly, few children on free school meals get into grammar schools, and those that do are likely to be the brightest and those with the strongest parental support.

Secondly, as Professor Stephen Gorard and Nadia Siddiqui of the School of Education at Durham University showed in their paper, Grammar schools in England: a new analysis of social segregation and academic outcomes, published in the British Journal of Sociology of Education on 26 March 2018, good performance by the few children from deprived backgrounds that get into grammar schools is due to the success of the selection process in picking the most able children and not to the progress made at grammar schools. As the researchers state: “Grammar schools use examinations to select children aged 10 or 11 who are predicted to do well in subsequent examinations at age 16. They select well, as evidenced by the high raw-score outcomes of these pupils five years later. This seems to confuse some commentators, members of the public and even policy-makers who assume that these good results are largely due to what happens in the school rather than the nature of the children selected. This is not a correct interpretation, as has long been pointed out in the sociology of education.”

Gorard and Siddiqui conclude: “Schools differ largely in terms of who attends them (Gorard and See 2013 Gorard, S., and B. H. See. 2013. Overcoming Disadvantage in Education. London: Routledge) and this seems to include grammar schools. Grammar schools in England did not confer a real advantage in the past and in their prime … and they do not do so now … They do not increase social mobility in comparison to comprehensive schools, and do not assist working-class pupils with social class mobility, although the figures for income mobility are not so clear (Boliver, V., and A. Swift. 2011. Do Comprehensive Schools Reduce Social Mobility? in the British Journal of Sociology 62.”

Gorard and Siddiqui noted that “not only do grammar schools in England take only a tiny proportion of pupils who are or have ever been eligible for free school meals, but those they do take have been eligible for fewer years. This, and the use of segregation figures, age in the school year and other derived variables, makes the presented re-analysis of the grammar school ‘effect’ novel. It may also help explain the substantive difference in findings between this study and earlier work using the less complete data available at that time, and without considerations of levels of enduring poverty.”

They observed that “every grammar school creates a much larger number of schools around it that cannot be comprehensive in intake, of necessity, because they are denied a supply of so many of the most high-attaining children. It does not matter whether these schools are officially designated as ‘secondary modern’ schools, or whether they offer different curricula or not. Also, the two sets of co-existing schools will and must differ in terms of a whole set of other pupil characteristics that appear to be related to selection at the 11-plus but are not directly selected for. These include special educational needs, first language and, less obviously, ethnicity and poverty. The secondary modern schools also receive less funding per pupil within their local authorities than do grammar schools.”

Gorard and Siddiqui are surely right when they conclude that “policy-makers and unthinking advocates always focus on grammar schools, whereas an equivalent claim to ‘we must have more grammar schools’ would be ‘we must have a lot more schools that are deprived of the most talented 15–20% of pupils in their catchment areas’. In areas with selective schools, the system is a clear driver towards increased social and economic segregation between schools, and all of the dangers that this entails – such as lower self-esteem and aspiration, poorer role models, poorer relationships and a distorted sense of justice.”

They found that on the basis of the prior evidence and the new analyses that they had undertaken, “the policy of selective schools has little to recommend it”. Dividing children into the most able and the rest from an early age “does not appear to lead to better results for either group, even for the most disadvantaged. This means that the kind of social segregation experienced by children and young people in selective areas of the United Kingdom, and in selective schools and countries around the world, is for no clear gain.” The United Kingdom, among others, has spent 20 years or more including pupils with special educational needs and disabilities into mainstream schooling. The argument was that whatever specific provision was needed could be provided in most mainstream schools, they could be taught separately for some tasks, and that it was better to allow them to socialise and gain educational experiences with their non-SEN peers. It is hard to see why exactly the same argument does not apply to the most able students in each area.

Put together, the findings of this research mean that grammar schools in England “endanger social cohesion for no clear improvement in overall results. The policy is a bad one and, far from increasing selection, the evidence-informed way forwards would be to phase out the existing 163 grammar schools in England.” Grammar schools are no better or worse than the other schools in England once their selected and privileged intake is accounted for. As Gorard and Siddiqui notes “there is no reason for them to exist”.

Nor does the research mean that schools should not use any form of internal ‘setting’ by ability in any phase. In the absence of grammars it is still currently possible for high-ability pupils to be taught together for at least some of the week. But the richer and more able pupils currently in grammar schools would then mix with a wider range of peers, especially those with learning challenges, in all classes and years that did

not use setting, all vertical structures such as ‘houses’, and in sports, play and extra-curricular activities. The importance of inclusion is not just about those with learning difficulties or disabilities; it can also be about including the most able and advantaged at age 11 in the general school mix.

There are other factors leading to stratified entries to schools. Some of these, such as changes in the local economy, transport in rural areas and residential segregation, are beyond a quick policy or educational fix. But some, such as the continued existence (and planned expansion) of schools that are selective by religion, could be abolished at a stroke. Any improvement in one is likely to have a beneficial impact on the others, but none of these further problems, in the view of Gorard and Siddiqui, is an argument for making the stratification worse by retaining or expanding grammar schools.

Other research

This research is the most recent, but there has been a lot of other research on this issue. It has been widely reported in Education Journal and elsewhere, so what follows is a brief summary and a link to the original research documents.

The Education Policy Institute published a report, Grammar Schools and Social Mobility, on 23 September 2016. It came to the following conclusions.

• Once prior attainment and pupil background is taken into consideration, EPI found no overall attainment impact of grammar schools.

• At school level, grammar school pupils perform highly in raw attainment terms. This high performance is driven however by the very high prior attainment and demographics of pupils in grammar schools.

• Pupils who are eligible for free school meals (FSM), a proxy for disadvantage, are under-represented in grammar schools. Only 2.5 per cent of grammar school pupils are entitled to FSM, compared with an average of 13.2 per cent in all state funded secondary schools and 17% in selective areas with grammar schools.

• A main cause of this significant under-representation of disadvantaged pupils in grammar schools is that, by the time the ‘11 Plus’ entry exam (or equivalent) is taken, 60 per cent of the disadvantaged attainment gap – equivalent to 10 months of learning by this stage – has emerged.

• EPI did not find a significant positive impact on social mobility. The gap between children on FSM (attaining five A*-C GCSEs, including English and Maths) and all other children is actually wider in selective areas than in non-selective areas – at around 34.1 per cent compared with 27.8 per cent. EPI’s analysis indicates the reason for this is grammar schools attract a larger number of high attaining, non-FSM pupils from other areas and so, in selective areas, there is a disproportionately large number of high attaining, non-disadvantaged children. Indeed, pupils travel, on average, twice as far to attend a selective school as a

non-selective school.

• Pupils eligible for Free School Meals in wholly selective areas that don’t attend a grammar schools perform worse than the national average.

• An expansion of grammar schools in areas which already have a large number of selective schools could lead to lower gains for grammar school pupils and small attainment losses for those not attending selective schools – losses which will be greatest amongst poor children.

On 12 December 2016 EPI published a second report, Grammar schools and social mobility – Further analysis of policy options, which further concluded that “it will be difficult for the government to identify areas for grammar school expansion that will avoid damage to pupils who do not access the new selective places, where there is public demand for new selective places, and high disadvantage. We also conclude that the Government’s present stated strategy of expanding existing grammar schools is likely in a majority of such areas to reduce the average attainment of disadvantaged pupils and is therefore unlikely to improve social mobility. A more promising approach in the most disadvantaged and low attaining areas may therefore be to focus on increasing the quality of existing non selective school places, as has been successfully achieved in areas such as London over the last 20 years.”

Links to both reports are: https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/grammar-schools-socialmobility/ and https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/grammar-schools-social-mobility-analysis-policy-options/

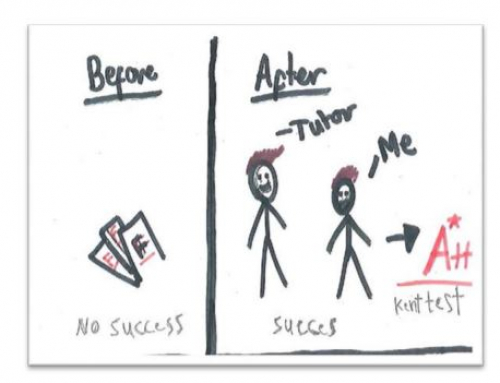

Education Datalab published a report on 22 March 2018 by John Jerrim and Sam Simms, Why do so few low and middle-income children attend a grammar school? New evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study, published by UCL Institute of Education and Education Datalab. As John Jerrim pointed out: “It has long been thought that ‘coaching’ for entrance tests is likely to be important and, despite claims of tests being ‘tutor-proof’, may provide an unfair advantage to children from an affluent background. Today, I can provide hard evidence that this is the case.”

Affluent families living in selective education areas in England are much more likely to invest in private tutoring services than lower-income families. This is particularly true in English and mathematics – subjects covered in grammar school entrance tests – but less so for science – which is not covered in the entrance tests. There is also less of a social gradient in the use of private tutors at the end of primary school in comprehensive parts of the country. In other words, private tutoring is disproportionately used by – and benefits – the rich within selective education areas.

Links to the Education Datalab website and the full research report are:

https://ffteducationdatalab.org.uk/2018/03/how-much-does-private-tutoring-matter-for-grammar-schooladmissions/

and https://johnjerrim.files.wordpress.com/2018/03/working_paper_nuffield_version_clean.pdf

A paper in Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, volume 12 issue 2, published some years ago in 2005, The fallibility of high stakes ‘11-plus’ testing in Northern Ireland by Pamela Cowan and Hugh Morrison of the Queen’s University of Belfast, sets out the findings from a large-scale analysis of the Northern Ireland Transfer Procedure Tests, used to select pupils for grammar schools in the province. The researchers found the selection process was flawed.

The candidate ranking system used to decide who got a grammar school place, which was similar to that used in England, had the potential to misclassify up to two-thirds of the test-taking cohort by as many as three grades. The link for this is https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09695940500143837.

There have been a large number of other reports published in recent years. All note that the number of children in grammar schools on free school meals, which indicates those from deprived backgrounds, are far fewer than the number than the number of such children in England and in particular

the number in selective areas. The Government’s claim that 60% of selective schools already prioritise the admission of children from disadvantaged children is misleading because they do not succeed in doing this.

The number of grammar school students from disadvantaged backgrounds is still extremely small, while those who transfer from the private sector, and are presumably from the wealthiest sector of society, are above average. Virtually all agree that grammar schools do not improve social mobility. Indeed, they do the opposite.

International evidence comes mainly from the PISA studies of the OECD, which take place every three years. For over a decade all PISA reports have shown that selection holds back equity and does not help quality. All the western countries at the top of the PISA results have comprehensive systems. The Netherlands is the only Western country that has a selective system but also gets high results, but it does not score so well with equity. The most recent PISA showed that the negative effects of selection were greatest in those systems that selected early (as England does) with the effect lessening the later selection took place. This has led some countries to push back the age of selection from 11 to 14 or 16.

The evidence contained in this article may appear to be biased against selection. It is not. It is simply that the vast majority, arguably all recent serious research, comes to the same conclusion. Only Ministers seem to have come to a different conclusion.

This article first appeared in the Education Journal edition of 15/5/2018. We thanks the editor, Demitri Coryton, for allowing it to be reproduced here.