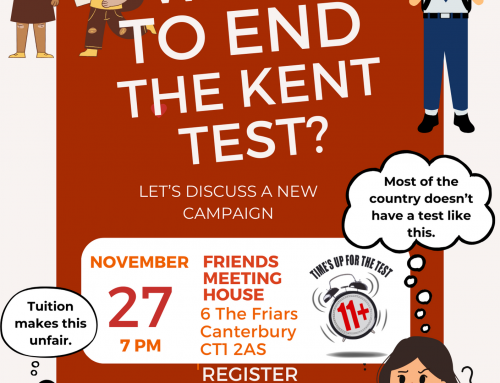

It is a persistent undercurrent in English educational debate, but it is peculiarly English: should academic selection at the age of 11 be restored?

Boris Johnson, perhaps in response to perceived UKIP pressure, has declared himself in favour of more grammar schools, and Teresa May, more cautiously, has welcomed plans for a satellite grammar school in her constituency of Maidenhead. In Kent, the Weald of Kent grammar school is preparing a new proposal to establish what is either (depending on your view) a new grammar school in Sevenoaks or a satellite site in Sevenoaks.

The arguments for restoring grammar schools are couched in terms of opportunity and social mobility: Boris Johnson called them mobilisers of opportunity. But the evidence to support this is almost non-existent.

There remain 164 grammar schools in England, and their socio-economic make up does not support the proposition that they turbo-charge social mobility: in all areas where there are grammar schools, the proportion of pupils on free school meals (FSM) is significantly lower in the grammar schools than in the area as a whole (1).

There’s little evidence to suggest that grammar schools work in the way their proponents suggest: research by Professor Ruth Lupton found that grammar schools work well for those who attend them, but few FSM pupils succeed in doing so. Moreover, the OECD international evidence (2) is clear that early selection is associated with lower performance, particularly from more deprived social groups.

More fundamentally, the argument for grammar school depends on four assumptions all being true. The first assumption is that a test for academic ability at age 11 can be reliable; that is, that a test at age 11 will reliably discriminate between those who are academically able and those who are not.

In fact, all tests have a high error rate, either because the tests do not measure accurately what they purport to assess, or because of random variations in performance on the day of the test, or because of marker error. Some evidence suggests that up to a third of pupils may be given the wrong national curriculum level (3).

The second assumption is that it is possible to test for academic ability at age 11 in a way which is valid – that is, that a test performance at age 11 will be strongly predictive of performance at ages 12, 13, 14, 15 and beyond. But the evidence is that children develop at different speeds and in different ways: those who perform well on a test at age 11 may not perform well at 12; those who perform relatively badly at 11 may perform better at 12.

The heyday of the 11-plus, and of grammar school education, was a time when psychologists believed academic ability to be fixed, stable and predictable, the research evidence now is clear that it is none of these.

The third assumption is that it is possible to design tests which have high specificity – that is, that they test academic ability and nothing else, such as socio-economic status. But the evidence is to the contrary: poorer children have always been under-represented in grammar schools, and even in the 1950s the differential performance of girls and boys at age 11 caused test assessors to scratch their heads about how many places to provide for each gender.

The poor were under-represented in the grammar schools of the 1960s when Brian Jackson and Denis Marsden published their classic study Education and the Working Class, and they are under-represented now: in 2012, FSM rates were 1.9 per cent at grammar schools and 16 per cent across all schools.

The fourth assumption is that it is possible to identify a defined group of pupils who will benefit from a grammar school education by comparison with the rest of the population: this was a principle of the 1944 Education Act with its vision of grammar, technical and modern schools. When grammar schools were widespread, the selected proportion varied hugely from area to area and it still does: approximately six per cent in the Birmingham grammar schools and, just 20 miles away, about 30 per cent in Rugby. Both cannot be correct.

For the argument in favour of grammar schools to be sustainable, all four of these assumptions need to hold: it needs to be possible to define valid, reliable, specific tests which accurately identify a group who will benefit from grammar schooling. In practice, none of the assumptions hold; there is no academically credible argument in favour of selection for grammar schools at age 11.

Of course, some existing grammar schools do a good job for those who attend them, but that in itself is not an argument for sustaining or extending them: few of those in favour of “more grammar schools” are willing to say what they really mean, which is “even more secondary modern schools” or “even more failure at 11”.

However, and it’s an argument which barely needs making in most countries, the evidence is strong: all children thrive on a high-demand, high-expectation curriculum in a school setting which allows for differential rates of learning and development. It is a mystery why the argument revolves in England in the way that it does when the intellectual arguments are so clear.

References

The Sutton Trust: http://bit.ly/1uYvibc

Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools, OECD: http://bit.ly/1zyy1HG

Reliability, validity, and all that jazz by Professor Dylan Wiliam: http://bit.ly/1rxP9c1

————————-

With thanks for permission to reproduce to Pete Henshaw, editor Secondary Education Bulletin http://www.sec-ed.co.uk/ where this article first appeared and Professor Chris Husbands, director of the Institute of Education, London. https://ioelondonblog.wordpress.com/category/chris-husbands/