Just weeks after making a passionate One Nation-style address on the steps of Number 10, a speech that many felt had more echoes of Ed Miliband than Margaret Thatcher, Theresa May’s government floated the idea of lifting the ban, in place since 1998, on the creation of new selective schools. Half a century since Circular 10/65, the famous memo sent out by a Labour government, ‘requesting’, with typical English rectitude, that local authorities reorganise their schools along comprehensive lines we are back to battling over the issue of selection. Again.

Just weeks after making a passionate One Nation-style address on the steps of Number 10, a speech that many felt had more echoes of Ed Miliband than Margaret Thatcher, Theresa May’s government floated the idea of lifting the ban, in place since 1998, on the creation of new selective schools. Half a century since Circular 10/65, the famous memo sent out by a Labour government, ‘requesting’, with typical English rectitude, that local authorities reorganise their schools along comprehensive lines we are back to battling over the issue of selection. Again.

We already know what a nationwide selective system looks like. Unlike the NHS, the delivery of state education post-1944 was set up on the basis of a crude class differentiation. Faced with the 11+, a test that then (and now) largely reflects already acquired learning and existing social advantage rather than ‘natural intelligence’, the majority of young people, most of them from working class homes, were shunted into the second-class sidings of the secondary modern. Nor were the much lauded grammar schools all they were cracked up to be, particularly for working class children. According to the Crowther report in the late 50s, a staggering 38 per cent of grammar school pupils failed to achieve more than three passes at O level.

It was for such reasons that the movement for comprehensive reform, building through the 50s, achieved such success in the 60s and 70s. Few trusted the basis of the 11+ itself, many parents (including many Tories) felt rawly the rejection of their children, and Tory and Labour local authorities alike recognised the wisdom of building good schools for all. Peter Housden’s recent monograph on the transition to comprehensive education in his home town of Market Drayton, The Passing of a Country Grammar School, is a particularly lucid case study of both the hard administrative graft and political negotiations that lay behind the shift to all-in schooling, as well as the many individual and social benefits it bequeathed.

Coupled with a progressively higher school leaving age, comprehensive education offered millions of young people hope, a more robust sense of self and, of course, the chance to gain qualifications. The percentage of young people gaining five O levels (now GCSEs) rose from 23 per cent in 1976 to 81 per cent in 2008. Those in education at age 17 grew from 31 per cent in 1977 to 76 per cent in 2011 and those achieving a degree rose from 68,000 in 1981 to 331,000 in 2010, an almost five-fold increase. These numbers have kept on rising.

Inevitably, there were problems – many that we still grapple with today. How do you create a system of local schools broadly comparable in quality in a wildly unequal and divided society? Occasionally, different ideas have got mixed up; ’progressive’ education (itself an inexact, capacious term) is not synonymous with comprehensive education, although the media would happily have some of the wilder extremes of the former be taken as typical of the latter.

Nervous governments have never tackled any of these problems head on. In the 80s and 90s ‘parental choice’ became the vogue, a superficially appealing but fatally ambiguous term that enfolded official attempts to offer alternative routes – from CTC’s to elite faith schools – to many families previously served by the grammar schools. Latest government research shows that many of the converter academies and free schools created since 2010 tend to have a lower proportion of disadvantaged pupils than their surrounding communities.

One thing is very clear. The grammar schools, and their powerful supporters and stories, never really went away. There are 163 grammars, and fifteen areas remain fully selective to this day, cleaving whole populations down the middle in brute, unimaginative fashion. In large cities like Birmingham and London, the grammar schools continue to siphon off the so-called ‘best and brightest’ young people almost entirely from better-off homes), insidiously dividing friends, families and communities, and making the job of surrounding non-selective schools that much harder.

Yet the grammar school story remains one of the most enduring and embedded narratives in English society to this day: the boy or girl from humble origins who rises to power and prominence by means of a selective education. By contrast, two equally important life narratives rarely get a look in: the child failed by a secondary modern schooling, or the young person, often from a humble background, who went to a comprehensive and flourished. Justine Greening is the first education secretary to be educated at a comprehensive and I was pleased to see Stephen Crabb, contender for the Tory leadership, talk of his ‘fabulous education at a really good comprehensive school across the road from the council house where I lived’.

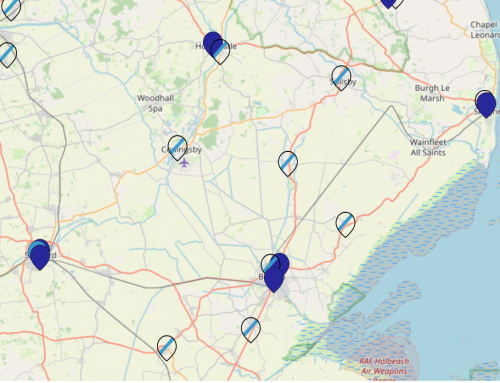

Direct comparisons between selective and comprehensive areas are notoriously tricky. According to government figures, some selective local authorities have inflows of over 60% of their year seven grammar school intake from other local authorities; similarly, comprehensive areas will lose some of their more high attaining pupils to selective schools across the border.

However, fully selective areas present a pretty clear picture of the disbenefits of the grammar/secondary modern divide. In 2013, Chris Cook of the Financial Times compared fully selective areas like Kent, Bucks and Lincolnshire with the rest of the country and found that poor children do significantly worse at GCSE than their peers in comprehensive areas. Cook also found that ‘the net effect of grammar schools is to disadvantage poor children and help the rich.’ Able children eligible for free school meals are far less likely to get into selective schools.

What a contrast with the many achievements, indeed triumphs, of so many non-selective schools across the country, especially in London, now considered to have the best state schools in the country. Significant investment under New Labour and collaborative initiatives like the National and London Challenge, gave a much needed boost to all-in schools. Local authorities like Hackney turned its family of schools round over a decade, with stunning effect. When attention is paid to the right things – boosting resources, improving teaching, creating a spacious, pleasant environment and encouraging positive behaviour – local schools have improved massively, and parental confidence rises as a consequence.

One proof of this success is that many on the political right have finally grasped the power and potential of comprehensive education, which they prefer to rebadge for themselves as ‘non-selective excellence’. Inevitably, this Tory led evangelism is a double-edged sword. Millions have been wasted on needless and divisive structural reform, pushing the academy and free school model, and more generally, a rigid test driven, little Englander view of education itself. The system remains constantly at risk of privatisation, given the big money and philanthropic pride now at play in the national and global education market.

For all that, we need to recognise that some of our allies over the next few months will come from parts of the education world we have been used to doing battle with previously, from the leaders of the powerful educational chains like ARK to leading right wing think tanks like Policy Exchange and Bright Blue.

Number 10 will work hard to dress up their plans as being all about helping lower-income families. However, given the tiny numbers of children from poorer backgrounds who currently pass the 11+, schools will have to alter their means of entry or lower the pass rate in order to achieve this, which surely defeats the point of selection?

Whatever the rationale, the creation of new selective schools will not only create thousands more children who feel themselves to be failures but will decimate many of the country’s excellent comprehensives. Ofsted chief and former East London head, Sir Michael Wilshaw, an outspoken opponent of grammars, said recently, ‘If someone had opened up a grammar school next to Mossbourne Academy, I would have been absolutely furious as it would have taken away those youngsters who set the tone of the school. Youngsters learn from other youngsters and see their ambition; it percolates throughout the schools. If the grammar schools had siphoned off those top 20 per cent, we would have floundered.’

This fresh row over selection is also a dangerous distraction from some of the serious problems that state schools currently face. The English system is in a complete mess, cleaved in half between academies (many of them run by mediocre academy chains) and maintained school working in partnership with ever struggling local authorities.

What a contrast with the many achievements, indeed triumphs, of so many non-selective schools across the country, especially in London, now considered to have the best state schools in the country. Significant investment under New Labour and collaborative initiatives like the National and London Challenge, gave a much needed boost to all-in schools. Local authorities like Hackney turned its family of schools round over a decade, with stunning effect. When attention is paid to the right things – boosting resources, improving teaching, creating a spacious, pleasant environment and encouraging positive behaviour – local schools have improved massively, and parental confidence rises as a consequence.

One proof of this success is that many on the political right have finally grasped the power and potential of comprehensive education, which they prefer to rebadge for themselves as ‘non-selective excellence’. Inevitably, this Tory led evangelism is a double-edged sword. Millions have been wasted on needless and divisive structural reform, pushing the academy and free school model, and more generally, a rigid testdriven, little Englander view of education itself. The system remains constantly at risk of privatisation, given the big money and philanthropic pride now at play in the national and global education market.

For all that, we need to recognise that some of our allies over the next few months will come from parts of the education world we have been used to doing battle with previously, from the leaders of the powerful educational chains like ARK to leading right wing think tanks like Policy Exchange and Bright Blue.

Number 10 will work hard to dress up their plans as being all about helping lower-income families. However, given the tiny numbers of children from poorer backgrounds who currently pass the 11+, schools will have to alter their means of entry or lower the pass rate in order to achieve this, which surely defeats the point of selection?

Whatever the rationale, the creation of new selective schools will not only create thousands more children who feel themselves to be failures but will decimate many of the country’s excellent comprehensives. Ofsted chief and former East London head, Sir Michael Wilshaw, an outspoken opponent of grammars, said recently, ‘If someone had opened up a grammar school next to Mossbourne Academy, I would have been absolutely furious as it would have taken away those youngsters who set the tone of the school. Youngsters learn from other youngsters and see their ambition; it percolates throughout the schools. If the grammar schools had siphoned off those top 20 per cent, we would have floundered.’

This fresh row over selection is also a dangerous distraction from some of the serious problems that state schools currently face. The English system is in a complete mess, cleaved in half between academies (many of them run by mediocre academy chains) and maintained schools working in partnership with ever struggling local authorities.

Most schools face substantial funding cuts, post austerity. There are severe teacher shortages in key subjects, an imminent crisis looming over recruitment of the next generation of school leaders and a general sense of professional overload. If Theresa May’s government really wants to improve the chances of ‘left behind’ Britain, it would do far better to turn its attention to solving these problems and seeking, with the ruthless efficiency we know the Tories possess, to improve all schools, not creating yet another divisive tier.

Melissa Benn is a writer and campaigner

Article first appeared in Education Politics www.socialisteducationalassociation.org