A report by Fran Abrams in the Guardian revealed that the number of grammar school places has risen in the last five years, but the number of children sitting the 11-plus test has not matched this rise. She said, ‘selective schools grew by 5.4% – about 1,200 pupils in total – but the numbers taking the 11-plus test didn’t keep pace; they grew by just 2.4%, in a period when the numbers of 11-year-olds were also rising.’

A report by Fran Abrams in the Guardian revealed that the number of grammar school places has risen in the last five years, but the number of children sitting the 11-plus test has not matched this rise. She said, ‘selective schools grew by 5.4% – about 1,200 pupils in total – but the numbers taking the 11-plus test didn’t keep pace; they grew by just 2.4%, in a period when the numbers of 11-year-olds were also rising.’

This suggests that the academic standard required to secure a selective school place has most likely fallen. It also makes a mockery of the recent government policy to expand selective education through the £50 million a year ‘Selective Schools Expansion Fund.’ If the government’s flawed ideal was the idea of educating higher attaining pupils together, the expansion has more likely just changed the mix of pupils attending grammars to include pupils who are lower down the attainment scale. This also casts doubts on whether grammar schools are as popular as the government think, it certainly suggests that many parents are not keen on entering their 10 year olds for a high stakes 11-plus exam.

Grammar schools have always filled their spaces in creative ways, the Guardian highlights the fact that pupils who win grammar places through appeals have not necessarily passed the 11-plus. CF’s Chair, Dr Nuala Burgess points out that these parental appeals often favour middle-class parents. “I would like to ask those grammar schools: are they taking those pupils from disadvantaged families? We know a large proportion of those in grammars tend to be more affluent.”

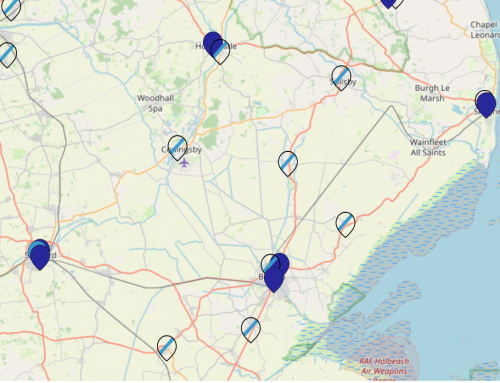

CF statistician and data expert James Coombs has been researching how 11-plus scoring has changed in Bucks as grammars expand, with little transparency about how they determine a pass or fail score. He points out that the proportion of Bucks children passing the test has risen from 27% to 34%. It clearly can’t be the case that Bucks pupils are suddenly cleverer! So it appears that the test providers must be lowering the standard needed to attend a selective school. James has been fighting a long-running legal battle with 11-plus test provider CEM to release ‘raw’ scores and explain the standardisation process, to help everyone understand how grammar school entry really works.

The losers in the expansion of grammar schools are the heroic non-selective schools in selective areas. These schools will happily serve their communities and admit all the pupils that the grammar schools decide they don’t want. Talking about these schools is complicated because they have no widely accepted name. The term ‘secondary modern’ is out of favour, but these are not true comprehensive schools because the balance of pupils is changed, and they admit mostly pupils lower down the attainment scale. As grammar schools expand these schools will take even fewer ‘high attaining’ pupils and the change in their pupil profile will be more pronounced. The government has thrown money at the expansion of grammar schools without any kind of impact assessment on what this means for these de facto secondary modern schools.

The ‘secondary modern’ school featured in the Guardian piece is Herne Bay High, a popular school in a Kent coastal town. The principal, Jon Boyes, talks about the lack of care for historic selection percentages. He said, “What I am against is the uneven playing field we’re on. If we’re in a system where 20% are meant to go to grammar school, then they should make it 20%. ”

Kent County Council put it in writing about twenty years ago that a quarter of Kent pupils should attend selective schools, yet now the proportion attending grammars has risen to a third of pupils. It’s a similar picture in other selective areas. Grammar schools used to be part of a system of education. There was a plan for every pupil who was part of this system – however flawed the plan might have been. Now, with no plan, and no review, grammar schools have morphed into schools that are about ‘parental choice’ with no overall overview of the system effects of academic selection. This, despite the fact one in five children in England live in a selective area. The grammar schools themselves decide what ‘selective’ means, based on their own needs, with no thought for other schools. Grammars choose who they will admit, and who they will reject and send to a secondary modern school.

It is not right that this power imbalance dominates education in every selective area. Grammar schools have the prestige, parents are proud to send their children to them (even if they failed a selection test), Ofsted note their unsurprising exam results and give ‘outstanding’ ratings to fuel demand further. In a schools market selective schools win, and grow, and no one seems to care about what happens to the children rejected and sent to schools that are not comprehensive schools.