There is a widely held view that mixed-ability comprehensive schools ‘fail’ bright children, but there is not much evidence to back this up.

There is a widely held view that mixed-ability comprehensive schools ‘fail’ bright children, but there is not much evidence to back this up.

Here are some reasons why this is nonsense.

Results for ‘bright’ pupils in comprehensive schools are on a par with those attending grammar schools

Some studies show a tiny results advantage for pupils attending grammar schools. The Education Policy Institute showed that pupils attending grammar schools in fully selective areas achieved on average 0.1 of a grade higher in each of eight GCSEs. This is a tiny difference, but other research has found no results boost at all. A large scale study led by Prof. Stephen Gorard of Durham University looked at the results of more than half a million pupils in England, and found that grammars are no better or worse than non-selective state schools in terms of their pupils’ progress or attainment. This study, unlike most others, adjusted for background factors that influence results such as affluence, prior attainment etc. Prof Gorard said, ‘The apparent success of grammar schools is due to pupils coming from more advantaged social backgrounds, and already having higher academic attainment at age 11.” So it is clearly a myth that ‘bright’ children do better in grammar schools than comprehensives.

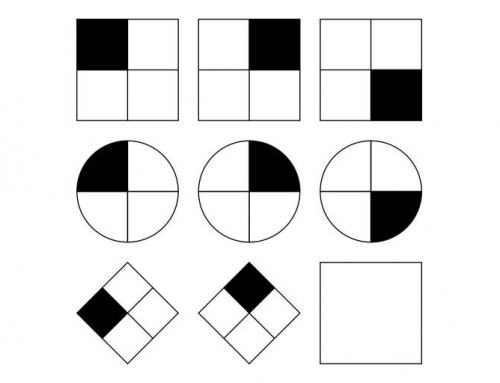

Comprehensive schools do not have ‘one size fits all’ classes, they differentiate between pupils

In a typical selective county 25 – 30% of primary pupils will attend grammar schools. In a typical comprehensive area this ‘top’ quarter of pupils would generally receive sufficient academic challenge at a comprehensive school by being placed in sets where they will have lessons pitched to their level. A study showed that 96% of secondary pupils are placed in ‘ability’ sets or streams for maths, while 76% are in sets or streams for science in year 10.

Nick Gibb, the current School Minister, said recently that there is no need for more grammar schools because, “Setting and streaming of pupils is common practice in secondary schools and enables teachers to tailor lessons to suit pupils of similar abilities and ensures that the highest ability pupils are offered additional stretch.”

In classes without ‘ability’ setting teachers are trained to differentiate between pupils and ensure there is sufficient challenge. Schools are judged on pupil progress based on a child’s attainment level in primary school SATs, with published data showing how much progress high attaining pupils have made, and Ofsted reviewing this data. It is in schools best interests to ensure ‘bright’ pupils achieve their potential and are not overlooked, and schools care about the academic success of all their pupils.

There is no special educational need that suggests grammar school pupils need entirely separate schools

There is an unfounded belief that the children attending grammar schools are so unusually bright that they are unsuited for a regular secondary school, yet the percentages do not back this up. In Kent, the biggest selective county, around a third of secondary pupils attend grammars at age 11, while half Kent’s pupil population attend grammars for sixth form. These secondary pupils are a huge body of pupils and not a small minority with unusual needs. It is possible that some proud parents are glad their child will be educated with others of their academic level in grammars, however they would not be short of peers of a similar level in any regular ‘mixed ability’ school.

The comprehensive school system sends hundreds of thousands of pupils to university every year

In the era when grammar schools were introduced these were a small minority of pupils receiving an academic education and aiming for university, now a wide range of people go to university and around 38% of 18 year olds access higher education, while overall 52.3% of adults aged 25 to 34 have gained qualifications higher than A levels. The establishment of the comprehensive school system has led many more people to access higher levels of education and improve their skills and qualifications. The grammar school system rationed this sort of ambition to a minority of pupils selected though a test when they were 10 years old.

Sometimes an anti-comprehensive, pro-grammar, stance stems from prejudice and fear

Sadly, when views about grammar schools versus comprehensive schools are unpicked prejudice can sometimes be found. Some regular comments about the need to isolate ‘brighter’ children in grammars include:

‘Bright pupils are bullied if they care about doing well at school.’

‘Comprehensive schools are full of children who don’t want to learn who mess around in lessons.’

‘Comprehensive schools have terrible behaviour an the teachers can’t teach.’

There is a longstanding myth that comprehensive schools are rough places full of rowdy pupils who do everything they can to disrupt lessons. In a minority of schools there are behaviour problems, but in the vast majority of schools poor behaviour is controlled and lessons inspire productive learning. Teachers are trained to deal with poor behaviour, policies are in place to mitigate this, and Ofsted judges behaviour ‘good’ in the majority of secondary schools.

There also seems to be a subtle class-based assumption that ‘rough kids’ from a certain social background are causing problems, and the ‘good’ children need to escape them. Grammar schools can be perceived as having a higher social status, similar to private schools, and it is believed that they contain middle and upper class pupils from ‘the right sort’ of homes. However, there are bullies and poor behaviour in every school, even grammar schools. The idea that children should be sorted between different education establishments based on social factors such as ‘willingness to learn’ is not an idea that stands up to scrutiny! It is snobbish and quite plainly untrue to suggest working class families have no interest in the behaviour of their children, and less interest in their children working hard and doing well at school.

In conclusion, the myth that comprehensive schools are failing ‘bright’ pupils is not backed up by evidence, and it is clear that many young people thrive in this school system and go on to find higher level qualifications beyond school.

Read more from our grammar school myths series HERE.