The idea that there are two types of children needing different routes to academic or vocational education is supported by many people. However, it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny that secondary age children can always be divided to neatly fit these two boxes. How many ‘academic’ children love art, design, music or cookery? Can it be right to deny ‘less academic’ children access to history, science or the study of literature? These important subjects can inspire children of all attainment levels even if they have no intention of studying for a degree.

The idea that there are two types of children needing different routes to academic or vocational education is supported by many people. However, it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny that secondary age children can always be divided to neatly fit these two boxes. How many ‘academic’ children love art, design, music or cookery? Can it be right to deny ‘less academic’ children access to history, science or the study of literature? These important subjects can inspire children of all attainment levels even if they have no intention of studying for a degree.

The idea that an academic versus vocational divide should happen at ten years old using the result of an 11-plus test is an old fashioned idea. When the selective school system was widespread in the 1960s the school leaving age was 15, now children stay in education until they’re 18. It makes no sense to divide children to differing career pathways so young. In most cases children and parents support learning the same subjects at secondary school, there is some divergence when subject choice is offered around age 14 for GCSEs, and then at age 16 different pathways are available, some of which will be vocational and some will lead to higher education.

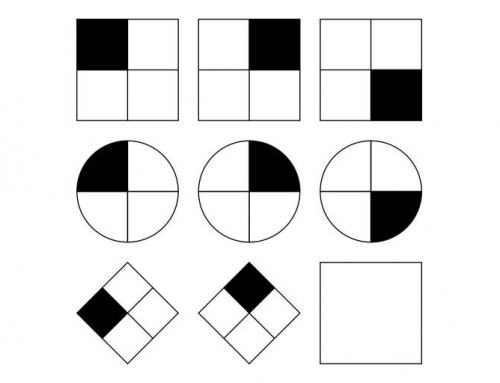

In modern day selective areas there is no difference between the curriculum on offer in grammars schools and the non-selective schools. All the pupils will study an academic curriculum and sit the same GCSE exams, and this makes a mockery of the idea that any divide at age 10 is still needed. In comprehensive schools the top 25% ‘academic’ pupils who might have passed an 11-plus, if one were available, mix with the other pupils from their community and have just as much chance of getting good grades as any pupil in a grammar school. Many schools chose to offer top sets, and this has the same effect as clustering pupils in grammar school classrooms but offers flexibility and does not rely on a stressful one-off test that is often inaccurate.

It was clear, even in the height of the grammar school era, that divisions between secondary modern schools, and grammar schools did not work. Many children were defined as needing ‘practical education’ in a secondary modern school when they were clearly capable of taking exams and attending university. Because of this secondary modern schools started to introduce exams at 16, with many children flourishing when they could study academic subjects. Nowadays it is widely accepted that all children will sit GCSE exams and have the opportunity to progress to a school sixth form. Most people think deciding a child’s entire education future when they start secondary school at age 11 is far too early. At a later age children can decide themselves whether to pursue academic subjects or a vocational route.

Those who call for more grammar schools because they like the sheep and goats notion that ‘some children are academic and some are vocational’ should pause and consider that our modern day school curriculum and exam system is designed for academic options for all pupils at secondary level. In selective counties like Kent, Buckinghamshire and Lincolnshire, that place a quarter or more pupils in grammar schools, this is the case too. The presence of grammar schools does not have any bearing on vocational options. If there was an appetite for different routes for some children it could be achieved in numerous ways without the return of divisive 11-plus tests and grammar schools.

To read more in our grammar school myths series click HERE.