By Jack Deasley, age 19, a student at Cambridge University

Liz Truss has hinted that she would change the law so that new grammar schools can open, as the favourite to be PM enters the last month of the Conservative Party leadership election.

Having attended both a non-selective school and a grammar school, I feel strongly against the polarisation that grammar schools create – which is inherent in any selective school.

Grammar schools were hugely popular in the first half of the 20th Century, where there were approximately 1,250 in 1965. Growing backlash led to Harold Wilson’s Labour Government issuing Circular 10/65 which requested local authorities to reorganise secondary schools in line with the comprehensive system – meaning no academic selection.

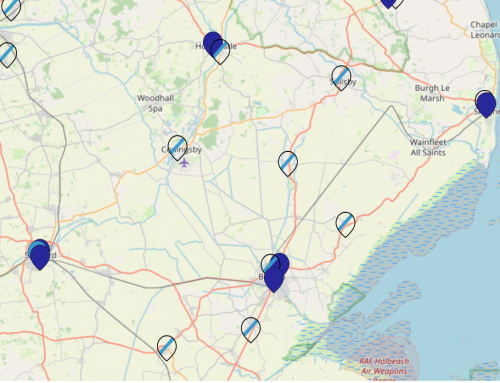

However, this was a request, not a demand, which left many grammar schools open in the counties of Lincolnshire, Kent, and Buckinghamshire. Tony Blair made the opening of new selective schools illegal in 1998, but it did not prevent existing grammar schools expanding.

Today, just 163 grammar schools remain in England but there have been recent calls to lift the ban, most notably the unsuccessful attempt by Theresa May in 2017. Liz Truss is the latest figure to pursue the reinvigoration of grammar schools as she claimed to be the “education prime minister.”

From my experience, there are three factors that make grammar schools unhealthy, for everyone in a selective area – not just those who fail the eleven-plus:

- The eleven-plus exacerbates inequality

Grammar schools are theoretically a tool for social mobility as they are free, but the eleven-plus allows them to be financially, as well as academically, selective – in favour of those who can afford tuition.

The Tutors’ Association revealed that 25% of students are tutored for the eleven-plus, and 50% in London, which gives these students an unfair financial advantage.

This leaves those who cannot afford tuition to go the non-selective schools in the locality – which are evidenced to perform below the national average. A feeling of inferiority at eleven years old is not the start to their secondary career they deserve, particularly when it is not deserved. I felt it for years, and my non-selective school rebuilt that confidence.

So, if Truss wants to be the true “education prime minister”, she may want to check the evidence. Then, she’ll realise that grammar schools do not increase social mobility, and the eleven-plus merely benefits the middle class.

- The toxic culture for the grammar school students

Criticisms of grammar schools typically focus on the detrimental impact of the eleven-plus on rejected students, but grammar school students themselves also suffer.

Firstly, the quality of education itself is not considerably higher than the average comprehensive school. A study by Durham University argued that, when you remove external social factors such as special educational needs, academic results are not significantly higher in grammars. This indicates that, while parents often pay for students to get into grammar schools, they may not actually aid any additional progress.

Secondly, grammar students not only don’t make additional progress, but they also suffer from the culture prioritising academic results over anything else. One article by a parent who sent their child to a grammar school in Kent revealed how students were “like factory workers” working solely for results, with limited pastoral care provisions.

Therefore, the focus on academic results means that there is not the space to develop in all areas of life, such as friendships, which eleven-year-olds should be allowed. Plus, the limited academic progress they make means it’s not a sacrifice worth making.

Liz Truss’ children go to a grammar school – she should recognise that they have flaws, which are of detriment to non-selective and selective school students alike.

- The unwelcoming culture for external students

Students who are rejected at eleven often have the choice to earn a place at the local grammar school’s sixth form, but the inferiority of failing the eleven-plus continues to loom.

There is often a division between the incoming students and the ‘original’ grammar students. The latter are no longer in classes full of “top 25%” students, but they continue to dominate the school. I was one of just nine incoming students at my grammar, and we noticed some of the entitlement that Jasneet Samrai describes – where non-grammar students were consistently considered “stupid.”

However, the most significant issue faced by external students is the treatment by some of the grammar school teachers. As the parent from Kent described, many were well drilled in producing results by getting students to copy from a PowerPoint, which put a dampener on the love of learning the students were meant to have.

It felt like there was a need to prove ourselves to the teachers, unlike the unconditional belief of the teachers at the non-selective school, which is evidenced when I was told I was “not a model student” – despite being on course to reach an offer from Cambridge University, participating well in class, and not having any disciplinary issues.

Therefore, does Truss want to expand a system where students don’t feel particularly welcome – nor capable?

Grammars can easily be seen as tools for social mobility on the surface – they have the resources to get students into the elite universities and dominate the league tables. However, the issues for non-grammar and grammar students reveal how the negatives outweigh the positives – unequal access, students becoming academic machines, and an unwelcoming culture.

Liz Truss should re-evaluate her policy for expanding grammars – it harms, not helps, the children that are going to rebuild the country.