I am sad to stand down after four years as chair of Comprehensive Future but am very pleased to stay on as vice chair, offering support to my impressive successor Dr Nuala Burgess.

I am sad to stand down after four years as chair of Comprehensive Future but am very pleased to stay on as vice chair, offering support to my impressive successor Dr Nuala Burgess.

Since its inception in 2003, Comprehensive Future has had a growing influence on the political and educational landscape. Over the last four years we have taken tremendous strides, including securing enough funding to take on a campaigns worker ( the excellent Jo Bartley), and previously a political and parliamentary officer ( Michael Pavey, who did a great job). Under Jo’s expert guidance, we have developed a brand new website, run two highly successful crowd funding campaigns, nurtured an ever growing twitter account and put on well attended fringe meetings at every major party conference in the autumn of 2018.

As I step down, I thought I would share a few thoughts on what I have learned as the Chair of this organisation – and how these lessons might aid campaigning in the years ahead.

The first, and most obvious, thing to say is that as long as there are politicians foolish enough to attempt to expand selection (yes, I am looking at you, Prime Minister) and so many areas where the 11 plus continues to operate, CF will always have a role to play. We must continue to put forward the evidence as well as make the case on more human terms as to why this is an unjust and inefficient plan.

The recent announcement of sixteen schools granted funds to expand, at a time of a general financial crisis in schools, shows that the fight must go on.

CF has played a big role in shifting political opinion on selection, but we mustn’t forget our equally important work on admissions. Over the past ten years, school admissions have become ever more complex, opaque and unjust. Increasing numbers of schools are using their so-called ‘freedoms’ to engineer a more favourable intake in a high stakes accountability system that rewards those who can attract the high prior attainers.

We have offered our expertise on admissions policies, and some ways to reform them, to the Labour shadow education team, and in the New Year we hope to explore the possibility of a nationwide survey on the ‘state of admissions’ with a major research partner.

For all these advances, I have learned, through my work as Chair, how hard it is to effect political change, even when people appear agree with you.

Despite many courteous, lively meetings with MPs, most of whom agree on the essential unfairness of the 11-plus and over complex admissions procedures, I have concluded that more of the same ( in other words, more lobbying of MPs) may not necessarily be the best way to persuade politicians of the need for change.

Of course, we need to continue to amass evidence, from as many sources as possible and, as with our recent documents on proposals for reform of both selections and admissions, present law makers with feasible alternative programmes.

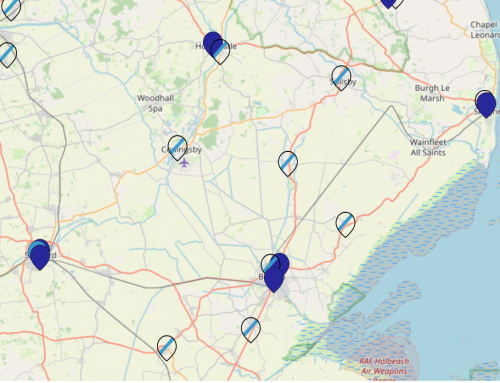

But it may be that we will achieve more in the year ahead if we concentrate on shifting public opinion, both through the media, and through more intense on-the-ground campaigning, particularly in the selective areas.

I have never stopped being astonished, and angered, by the fact that a system set up in 1945 and phased out in most parts of the country in the 1960s and 70s still operates in certain counties, and that no politician, of any party, seriously calls it out or proposes reform, possibly for purposes of electoral calculation.

However, what I have also come to understand is that where selection is entrenched, it can become an unquestioned way of life, even to those whose children are directly harmed by it.

So I believe there is more work to do, beyond the excellent work of our affiliate local groups, in reaching those parents who are faced with a deeply unfair and complex system but have not yet been moved to angry public expression about a test that damages the educational (and life) chances of a majority and causes anxiety to almost all.

Certainly, the lessons of educational history tell us that it is only when parents rise up and cry ‘Enough!’ that politicians have to take note.

Finally, we need to take a new approach in our long established efforts to prove to parents that comprehensive education can deliver an excellent education for all. Many parts of the country from inner London to Hampshire to Suffolk demonstrate that all-in schools can be truly excellent, as do high quality international systems in countries such as Finland and Canada.

Perhaps now is the time to bring together the many head teachers who feel the same, in an affiliate organisation that we have provisionally called Heads Together. Such a group would be able to talk authoritatively about how comprehensive schools really work, what they can achieve and the ways in which they bring together, rather than divide, local populations.

Finally, just a word of warning to Nuala. Most people think we are called Comprehensive Futures ( spot the additional s). I am afraid she will spend a lot of time correcting this misconception, insisting on the singular not plural usage. As I always say: for now, we’d be perfectly happy with just one Comprehensive Future!

Melissa Benn.

December 2018