By Roy Boardman

When, three years ago, I decided to write an autobiographical novel covering my years at Secondary School, 1948-1953, I began to think of the extent to which failing the 11-plus exam had affected my life and how attending one of the first London experimental Comprehensive Schools set things right.

When, three years ago, I decided to write an autobiographical novel covering my years at Secondary School, 1948-1953, I began to think of the extent to which failing the 11-plus exam had affected my life and how attending one of the first London experimental Comprehensive Schools set things right.

On the 11-plus day, I sat at a tiered wooden desk trying as hard as I could to copy what the girl in front of me was writing. Some of the questions I could make no sense of at all, including one about the number of sides on a cube. I copied ‘24’. Understandable when you didn’t know what a cube was. But what I more clearly remember is the anguish. How could I forget the post-Results Day meeting with my headmaster, who told my parents that although I was ‘no good at reading, writing an’ ‘rithmatic, ‘He’ll be able to do something with his hands.’?

We’d had it plugged into us, by teachers, that our 11-plus results would decide which kind of school we went to: Grammar, Technical or Secondary Modern. Not that these alternatives meant anything to us. All we knew was that Grammar was posh, probably not for us. On our parents’ side, failure would bring shame: not wearing the right posh coloured blazer bearing the Grammar School’s crest, blazing too on the cap, but in the end a mere Sec Mod cap that would make you feel that you shouldn’t be ambitious about your choices in life.

But I was lucky. My school was Walworth Secondary Modern (now Walworth Academy) in South East London, which was, not in name but in fact, one of the first Comprehensives in London. I like the capital ‘C’ and will never forget the school badge (a pilgrim walking through gates) or the school hymn (To Be a Pilgrim). At that time, the Comprehensive was a mission, a belief, not simply a way of giving us working-class kids opportunities like sitting GCE ‘Ordinary’ and ‘Advanced’ opening the gates to we pilgrims, but belief in ourselves.

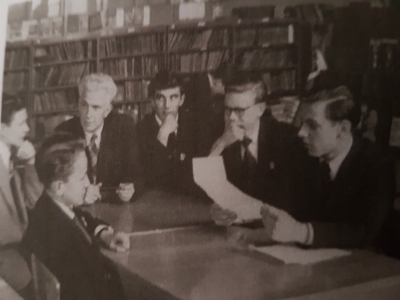

The teachers, mainly hurriedly trained in post-war Britain, were education missionaries. Their beliefs, together with those of the Headmistress Miss O’Reilly, are reflected in an article published in John Bull in 1951 (where, aged 14, I am described as ‘the embryo novelist’): ‘Once inside the school, with its freshly painted apple-green walls, its cheerful, purposeful activity, the grim institutionalism of the exterior fell away… No one I have met really seriously believes that it is possible to “type” a child at eleven … The intelligence test has still, mercifully, to be devised which can take adequate account of the X-factors in a developing personality.

Said Miss O’Reilly: “There is this inner force in people.” And she went on to tell a story of a boy who had been proved by repeated intelligence tests to be quite incapable of coping with academic subjects. But, since he pleaded long and eloquently, he had been allowed to try. He took his School Certificate with distinctions and rose to illuminate the sixth form!

‘Unlike the Grammar Schools, which still retain something of the cloister whence they came, the Comprehensive Schools mix the sexes as they mix everything else. And this, possibly, is yet another reason why the Grammar School heads, concerned for their high intellectual standards, regard them with aversion.’ In Miss O’Reilly’s opinion, however, co-education “leads to a much greater understanding”.’ (John Bull, February 1951)

It was the Head of English, Arthur Harvey, who had invited a John Bull journalist to ‘come and see’. Harvey was the Comprehensive School missionary of missionaries to whom I owe my career as a teacher, writer, British Council English Language Officer and Regional Officer South Italy, still going at age 81 as teacher of English as a foreign language and author of the novel Honky Tonk (a Cockney pub piano!), as well as award-winning published short stories and poetry. Thank you, Comprehensive School!