There is a widespread belief that in the height of the grammar school era, in the 50s and 60s, there was an expansion of opportunity for poorer children, who attended selective schools and found well paid careers that improved their life chances. This belief is fuelled by the fact many of us know older people who went to school in this era and achieved better jobs than their parents, or who might have been the first in their family to go to university.

There is a widespread belief that in the height of the grammar school era, in the 50s and 60s, there was an expansion of opportunity for poorer children, who attended selective schools and found well paid careers that improved their life chances. This belief is fuelled by the fact many of us know older people who went to school in this era and achieved better jobs than their parents, or who might have been the first in their family to go to university.

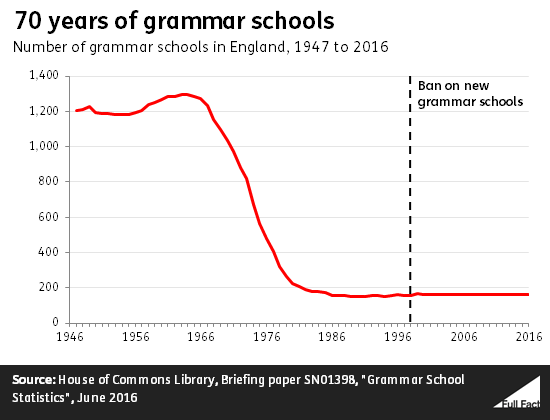

There is a feeling that since grammar schools converted to comprehensive schools in the 1970s things have gone backwards. Many people think that when grammar schools were phased out ‘bright poor kids’ no longer had a ‘leg up’ to a better life.

Here’s why all of this is just a myth.

The world of work changed significantly in the 1960s and 70s

The 1960s and 70s were a time of significant change in the world of work, driven by a range of economic, social, and technological factors. These changes coincided with the time when grammar schools and secondary moderns were the sole system of education, and people have attributed the improving opportunities for well-paid work to the system of education that was in place.

There was a shift away from manual work in this era, as the economy moved away from factory work and towards services, particularly finance and business services. This led to the growth of new industries and the decline of traditional manufacturing industries. There was also a rise of automation and computerization, as new technologies led to changes in the nature of work and the skills required to perform many jobs. There was also increasing diversity in the workforce, with a significant increase in the number of women and ethnic minorities entering the workforce, plus new employment laws and more opportunity for flexible working.

We regularly hear anecdotes about someone whose parents were from a mining community going to a grammar school and then becoming a successful as a manager, or someone whose parents worked in a factory attending a grammar school and going on to become a head teacher. It is highly likely that any system of education that was operating in the 1960s would have seen the same outcomes. The sons and daughters of working class parents achieved middle class jobs, simply due to so many new ‘white collar’ career pathways opening up.

If selective education was the reason for there being more opportunity we would expect to see areas that changed to comprehensive education in the early 70s see a dip in social mobility, while areas that retained grammar schools would see greater social mobility. However, a study by economist Franz Buscha looked at schooling patterns over time in different areas and concluded that selective schooling did not promote social mobility in England. Another study had similar findings, concluding, “The shift from grammar schools to comprehensives made little difference to social mobility,” pointing out that, “We found that the abolition of so many grammar schools in the 1960s and 1970s did little to change overall social mobility levels. Social mobility levels did rise during this period, but our analysis found no link to the rapidly changing nature of the school system.”

In the ‘heyday of grammar schools’ selective education was not serving the majority of pupils well

In the ‘heyday of grammar schools’ selective education was not serving the majority of pupils well

Imagine if every son or daughter of a low paid factory worker in the 1960s was given the opportunity of a high quality education, with the chance to sit exams and go to university? This was not the way it worked in the grammar school era! In the 1960s about 25% of pupils attended grammar schools, while 75% attended secondary modern schools. In secondary modern schools the pupils were assumed to be heading for practical jobs, and they did not have the opportunity to sit the same exams as those who attended grammar schools. Pupils in secondary modern schools left school at 15, at least until the school leaving age was raised to 16 in 1972.

The majority of working class pupils did not pass the 11-plus and go to grammar school, they were short changed with their education. The rationing of high quality academic education to only those who passed the 11-plus was increasingly unpopular, which was why parents generally supported the introduction of comprehensive education.

Poorer pupils were underrepresented at at grammar schools and did not achieve the same outcomes as wealthier peers

The 11-plus exam was used to sift pupils between grammar schools and secondary moderns, with the test often asking questions that included language or concepts that might be unfamiliar to working class pupils. This one-off exam was better suited to wealthier children who had the best primary education or well educated parents.

The 1954 Gurney-Dixon Report found that children whose fathers worked in ‘unskilled’ or ‘semi-skilled’ jobs were less likely to attend grammars. Children in these categories made up just over 20% of grammar school pupils, but 30% of pupils generally. An academic study from this time commented that “the lower working class are still markedly under-represented in the Grammar Schools”. At the end of the decade, experts were writing that grammar schools were “largely middle class”.

The Robbins report of 1963 also criticised grammar schools for not serving working class pupils. It pointed out that only 2% of pupils from a skilled manual background and 1% from an unskilled background went to university. It stated that although 26% of children were from unskilled backgrounds, just 0.3% of those achieved two or more A-levels at grammar schools. The report at said the structure of secondary education in the UK was “a matter of concern” and that “the absence of a common pattern in secondary education creates obstacles to access to higher education for many young people.”

Comprehensive education and increased access to university education has had a significant impact on social mobility

Comprehensive education means that now all pupils have the same opportunity to sit GCSE and A level exams, not just those who pass an 11-plus and go to grammar school. Nowadays many more pupils move on to higher education and access graduate careers. The expansion of university places means significantly more disadvantaged young people are achieving a degree than in the grammar school era.

In 2021, 24% of UK 18-year-olds from low participation neighbourhoods (areas characterized by lower levels of social and economic privilege,) were accepted to study a full-time undergraduate degree, compared to 14.1% in 2012. The higher education entry rate of state school students in England who were in receipt of free school meals at school, has increased from 13.0% in 2012 to 20.9% in 2021. More than a quarter (28.1%) of pupils in receipt of free school meals now move on to higher education. This varies by region, with half of pupils eligible for Free School Meals in Inner London progressing to higher education by age 19, compared to fewer than a fifth in the South East and South West. But in the height of the grammar school era only 0.3% of those from ‘unskilled’ backgrounds achieved two or more A-levels at grammar schools, and had the chance of progressing to university.

Anecdotes are not evidence, but the stories of those failed by selective education in the past deserve attention

The belief that grammar schools of old boosted the chances of poorer children is mostly fuelled by anecdotes about working class pupils who achieved success, yet the anecdotes of the many people who were let down by the selective school system are rarely mentioned.

My own mother passed the 11-plus and attended a grammar school, where she enjoyed elocution lessons(!) and became a teacher, escaping her working class roots and buying a home. Her sister, my aunt, failed her 11-plus, left school at 15 and became a cleaner, living in social housing her whole life. It would clearly be wrong to highlight only the grammar school success story from my family. I am convinced that my smart sparky aunt deserved much better educational opportunities, but she was let down by the selective school system. Should a test at 10 years old really define a whole life? These stories of pass/fail divides within families are commonplace, and they hurt all involved.

There are a few websites that highlight the stories of those mistreated by the selective school system old. You can find their stories on the Sec Mod website, or 11+ Anonymous, or the Wilsthorpe Project. Their views matter just as much as those who ‘won’ the grammar school place.

Grammar school systems today do not boost social mobility

There is not much evidence that grammar schools increased social mobility in the 50s and 60s when selective schools were commonplace, but if we look at grammar schools now there is a wealth of evidence that they are detrimental for social mobility. Counties like Kent, Buckinghampshire and Lincolnshire still operate fully selective school systems yet research looking at these areas sees no boost to social mobility. Kent contains 2 million people, 32 grammar schools, 66 non-selective schools, and a mix of wealthy communities and deprived coastal towns. It’s a fully operational ‘trial’ of a modern selective school system, but it produces poor results and social segregation in secondary schools. Low numbers of disadvantaged pupils access modern grammar schools, and wealthy parents game the system by hiring 11-plus tutors. Attainment gaps in selective areas are wider than comprehensive areas.

‘A splitting of the old working class into an educational us-and-them’

Roy Greenslade writing about the myth of grammar school social mobility exposes the misconceptions around this topic perfectly, and his article is worth a read. He says, ‘I often found myself revelling in the benefits of going to a grammar, regarding it as an invaluable social mobility mechanism that had helped to propel me up the ladder. I’ve heard any number of grammar school pupils from that era, the late 1950s and early 60s, say the same….It is necessary, however, to put what happened to all of us in perspective because the Britain of that time was very different from the country today, most especially in terms of the economy… Our schooling enabled us to take up a range of occupations crying out for our educational skills. Some went to universities (also growing in number) and then into even better jobs – the law, banking, administration and, of course, teaching. We were, to be frank, lucky. We baby-boomers were in the right place at the right time. Our grammar school was part of the reason for our success, but not even the major part. And the overwhelming unfairness, a splitting of the old working class into an educational us-and-them, was evident even then.’

Useful links:

• Franz Buscha’s study “Selective Schooling and Social Mobility in England”

• The Sutton Trust report “The Impact of Selective Education on Social Mobility”

• The Education Policy Institute report “Grammar Schools and Social Mobility”

• The National Institute of Economic and Social Research report “Grammar Schools and Social Mobility in England”

• The Joseph Rowntree Foundation report “Social Mobility and Education in Britain: Research Findings”

• Full Fact “Social mobility in the selective education era”

To read more in our grammar school myths series click HERE.