By Alastair Lichten

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and not Comprehensive Future policy.

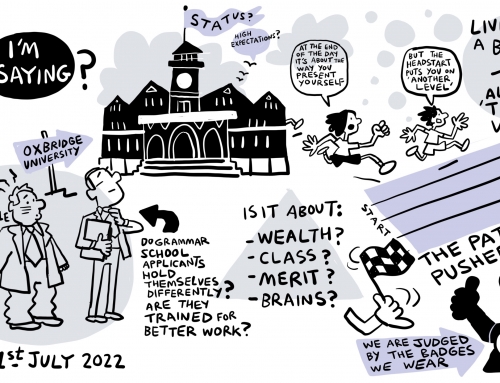

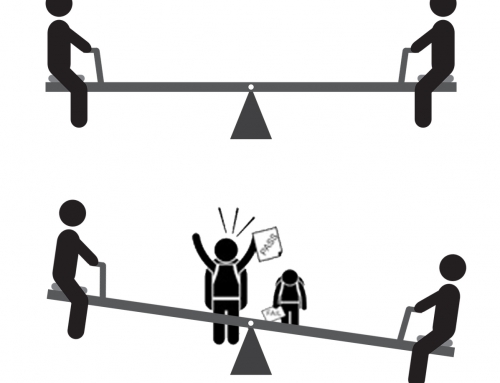

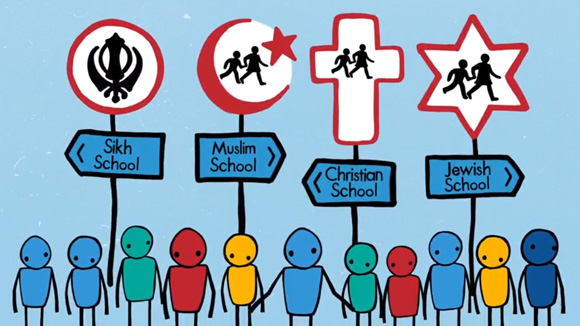

“Education, not segregation” was the rallying cry for opponents of the government’s “schools that work for everyone” plan to expand grammars and remove limits on faith academies’ ability to discriminate against prospective pupils based on religion. Study after study shows that (academically or religiously) selective schools lead to social selection which largely explains apparent differences in outcomes. Yet when it comes to segregation and discrimination, faith schools are often the elephant in the room.

“Education, not segregation” was the rallying cry for opponents of the government’s “schools that work for everyone” plan to expand grammars and remove limits on faith academies’ ability to discriminate against prospective pupils based on religion. Study after study shows that (academically or religiously) selective schools lead to social selection which largely explains apparent differences in outcomes. Yet when it comes to segregation and discrimination, faith schools are often the elephant in the room.

A comprehensive education system must be one that is open and inclusive for pupils of all backgrounds. This means going beyond open admissions. Although that’s an important start, we need to move towards not organising schools around exclusive identities.

Putting admissions controls in the hands of local authorities would enable them to plan for local school needs. More immediately it would allow us to drastically simplify the admissions process for families, sweeping away the labyrinthine system of selective or religiously discriminatory admissions.

Simply put, an education system where pupils or teachers are discriminated against because of their religious background, or where schools are organised around promoting a religion, isn’t and can’t be “comprehensive”.

Luckily, our community schools already show what a truly comprehensive education system could look like. People understand this on an instinctive level, which is why the descriptor of ‘community school’ continues to be used for community converter academies and free schools that are non-selective and have a community – rather than religious – ethos.

Such schools are widely known as ‘non-faith schools’, though this isn’t completely accurate. Some have (often extensive) Christian worship and leaders have considerable leeway to impose religious practices. The term can also be used to suggest that community ethos schools are a sort of opposite to faith schools; that whereas faith schools are organised around religion, community schools may be organised around irreligion.

In reality, no schools are organised around irreligion or atheism. Community schools are generally ‘non-faith’ in the sense that they are not expected to promote or oppose faith. In reflection of this, community schools teach locally determined rather than denominational religious education and are not permitted to religiously discriminate in the selection of staff, governors or pupils.

In a recent report on school choice, we argued that all schools should consult with their community on their ethos. As well as ensuring community schools continue to improve inclusion, this would reflect the diversity within state funded faith school communities. Many wish to more closely align to a community school ethos or to roll back selective admissions, particularly when they are simply the local school and uncomfortable with pressure to promote a more rigorous religious ethos.

In a comprehensive school system, basic requirements and examples of best practice would be promulgated at a national level. However, there would be very wide scope for local determination and experimentation, built on the basis of genuine consultation with school communities.

All schools would have to ensure their ethos was consistent with the Equality Act and children’s rights. This would mean that school values couldn’t be framed in exclusively religious terms. At all levels the religiously, non-religiously and irreligiously motivated would be free to feed in their views, but not in any special or privileged way, and they would need to translate their concerns into shared values.

Our community schools have successfully muddled through titanic social changes in the last three quarters of a century. In 1944 Britain was seen as a largely Christian country, and community schools reflected that. We are now a far more diverse and largely post-Christian society. The large majority of pupils and most of those feeding into schools’ ethoses will be non-religious, but as communities they will need to craft ethoses that are welcoming to families from all backgrounds.

Schools may need to make different accommodations based on their communities. Examples might be space for genuinely voluntary religious activities and clubs. The difference is that community schools make reasonable accommodation for a diversity of beliefs, rather than organising around a specific religion. This is why community schools are better placed to respect freedom of and from religion.

A truly comprehensive education system would require an end to selective admissions. But as apologists point out these are not the only drivers of segregation. Selective schools are usually planned around larger than average catchment areas, so could be an opportunity for local experimentation to promote inclusion and community cohesion. An example could be the University of Birmingham School which has radically broken away from traditional catchment areas to buck the trend in a city with some of England’s most segregated schools.

Catchment areas of high performing schools could be drawn to break down religious, ethnic and social divisions. Imagine what Northern Ireland could look like if we didn’t educate 93% of the next generation in sectarian, segregated schools.

A transition to a comprehensive system of community schools wouldn’t necessitate immediate changes to ownership. Where a foundation (whether a grammar or a religious trust) owns the land or buildings on which a state funded school is delivered then such property rights may need legal protection. There’s just no reason they should translate into any special influence in the running of the school.

A transition to a comprehensive education system requires many steps. Some may be simple and popular (albeit politically difficult), and others may be genuinely complex. Along the way there will be lots of compromises. But there’s nothing that requires us to take a step in the dark, or to lose sight of the freedom of belief and aspirations of all our communities.

Alastair Lichten is head of education at the National Secular Society and leads the No More Faith Schools campaign.