The September 2020 11-plus tests are likely to be the only form of nationally sanctioned, high stakes tests taking place anywhere in the western world this year.

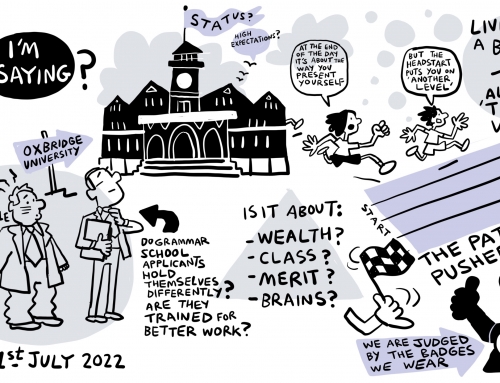

Abolished in most parts of England more than half a century ago, the 11-plus still exists in almost a quarter of England’s largest local authorities, and influences school admissions in dozens of others.

It remains deeply divisive, notoriously unreliable and a source of stress and anguish for hundreds of thousands of parents, teachers and children every year.

Teaching to the test, intensive rote learning and industrial scale private tuition are key factors in determining 11-plus results. This year most schools will have been closed, wholly or partially, for most of the summer term. So able children with affluent parents and/or those skilled at home teaching will, inevitably, have an even greater advantage.

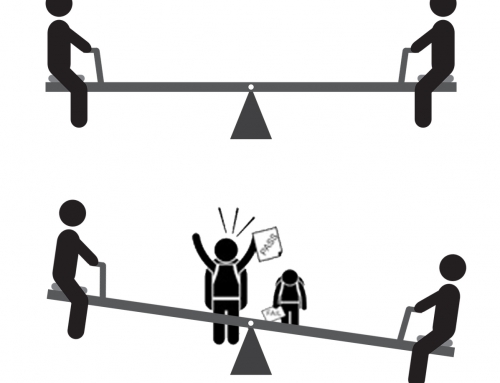

The 11-plus is designed to routinely fail 75% of 10 year olds. It is even more likely this year that children without affluent parents will start secondary school labelled as failures. The chronic social and economic inequalities deeply embedded in our society will be made much worse.

As the Government, quite rightly, cancelled all other national tests two months ago, what possible argument can there be for continuing with this year’s 11-plus?

- Will the pandemic have ended by then? Unlikely.

- Will an effective vaccine have been identified, tested and manufactured at scale? Impossible.

- Will social distancing measures have been abolished? No.

- Will all schools be functioning again in pre-pandemic mode? Almost certainly not.

The most rational policy would, therefore, be to follow the A level/GCSE precedent and simply suspend this September’s 11-plus tests.

Would most children themselves regret not taking the test this year? As the test is designed to fail 75% of them, it seems unlikely.

Would parents suffer additional stress by any delay in the allocation of school places for 2021? Some would be exceptionally vociferous, notably those who have spent heavily on private tuition. However, for the overwhelming majority of parents nothing would change.

Would an alternative system for allocating places at these schools be necessary? Definitely. Could it be worse? Absolutely not.

Exceptional times require exceptional measures. In September 2020, for example, not a single eighteen year old starting a degree course will have actually passed an A level examination.

Each of the 163 wholly selective schools, and the dozens of partially selective schools, follow exactly the same national curriculum as children in the remaining 4,000 secondary schools. Therefore, a one-year suspension of the 11 plus test would be far less problematic than a one-year suspension of A levels.

Admission by test in September 2021 could, for example, be replaced by random allocation, attendance at feeder primary school or distance from home to school. Or by any combination of these three criteria. This would be administratively straightforward, and require only minor legislative change.

What then for school admissions in September 2022? The Covid-19 crisis has forced us all, even those with the most entrenched ideological views, to think the previously unthinkable and confront reality.

The reality of 11-plus testing is simply this. There is no longer any educational reason for segregating children at 11. The survival of the test is entirely political and designed to reproduce social and economic inequalities.

So the way forward is clear:

- Suspend the September 2020 11-plus tests.

- For school entry in 2021, replace test results with a combination of feeder primary schools, residential proximity or random allocation.

- Consult all parents and teachers in the affected areas on school admission arrangements for 2022 and after.

All in it together, as in the world’s best schooling systems, or permanent, structural, social distancing with a vengeance? For most normal people, it’s a no brainer.

David Chaytor was the first Chair of Comprehensive Future, a former member of the House of Commons Education Select Committee, Chair of a Local Education Authority, and, previously, Head of Continuing Education in one of England’s largest colleges. He is writing this article in a personal capacity.

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and not Comprehensive Future policy.