By Dr. Alan Bainbridge

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and not Comprehensive Future policy.

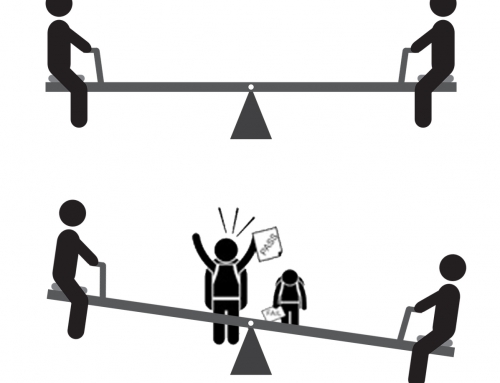

Recently a local online newspaper in Kent published the dramatic headline ‘The Best and Worst Schools in Kent based on GCSE results in 2018’. It then proceeded to list the top and bottom five schools, after which it published a full table of all the state secondary schools in Kent in descending Attainment 8 score. Selective schools filled the top 5 spots as the “best” schools, while non-selective schools were classed as the “worst.” As can be imagined the headline alone credited some level of controversy and the world of Twitter seized the opportunity to condemn what was at least extremely lazy journalism. Or at worst, some mendacious act to solicit more hits on their website to extract higher fees from the advertisers and sponsors who prop up this parlous state of journalism.

Recently a local online newspaper in Kent published the dramatic headline ‘The Best and Worst Schools in Kent based on GCSE results in 2018’. It then proceeded to list the top and bottom five schools, after which it published a full table of all the state secondary schools in Kent in descending Attainment 8 score. Selective schools filled the top 5 spots as the “best” schools, while non-selective schools were classed as the “worst.” As can be imagined the headline alone credited some level of controversy and the world of Twitter seized the opportunity to condemn what was at least extremely lazy journalism. Or at worst, some mendacious act to solicit more hits on their website to extract higher fees from the advertisers and sponsors who prop up this parlous state of journalism.

It was not even a great bit of writing. I would have enjoyed reading a well thought out piece on school ‘achievement’ if the sentiments behind it were meant to support some coherent viewpoint. But it even fell short of that as it simply provided the data with a few accompanying sentences to expand what each number meant. The following is the sum total for one school.

Tonbridge Grammar School was Kent’s best performing school in the 2018 GCSEs with an average Attainment 8 score per pupil of 77.9. Every single pupil at the school in Deakin Leas achieved standard 9-4 passes in both English and maths. All of its pupils also achieved five or more GCSEs at grade 4/C or above.

I tried to imagine the thought process that loitered behind those who decided to write this ‘article’ but, probably like them, slipped into lazy thinking and simply thought, “this is the sloppy way journalism is going.” I lamented the days of rigorous reporting in local newspapers and tried to console myself with the thought that at least it did provoke some sort of response – one of which I hoped would be a rather stern discussion on professionalism from a disappointed editor.

I even tried to forget the report, after all, I had offered a grumpy re-tweet on Twitter and fantasized how this was now bouncing around cyber-space, read by wise people who would nod approval and ‘like’ and re-tweet me. But something would not go away, I could not shake it off simply as ‘lazy journalism’, to be honest, I have much sympathy for hard-pressed junior journalists trying to make their way in a rapidly shrinking employment area. But the shoddy ‘Best/Worst schools in Kent’ report still did not sit easy with me for it represented, not only poor journalism, but also a threat to the purpose of education and if I am allowed to push the argument further, a threat to democracy.

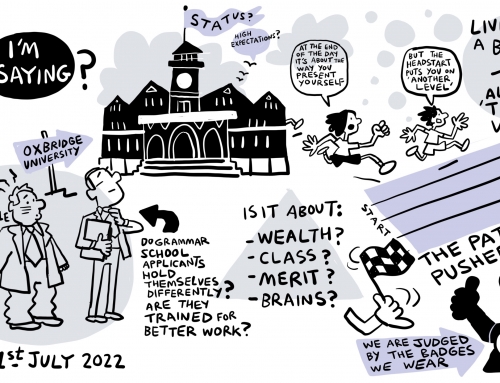

It is not just those who wrote this piece that see the ‘best/worst schools’ in the simple terms of GCSE results – this is also the view of our government and it emerges in the mindless mantra that continues to support endless SATs and testing children at the age of 10. Do these authors really, I mean really, deep down in their gut feelings, or even after hours of careful scholarly retrospection, do they really believe that the ‘best/worst’ schools can be attributable to an exam score?

Have they considered the impact of such announcements to the pupils, teachers and parents associated with those schools? The best, or the worst ones – what sort of world are we creating when ammunition is provided from the age of ten (this is when Kent ‘selects’ its children to attend one of the best or worst schools) to confirm that ‘you’ are either the best or the worst.

I recently had the pleasure to talk to a group of young people from Finland and I asked them how they knew which of their schools were good schools. They said that all their schools are good schools. I questioned them again about how they could be sure that their school was a good school, and to not even consider the thought that their school might be bad. The response was equally as quick and simple, “we trust our teachers” they said. It is significant that it is trust in teachers, not a test at the age of 10, or a list of exam grade averages that provides them with an understanding of ‘goodness’.

Such enlightened thinking: I only wish some of our journalists and politicians could take a similar stance and acknowledge, in policy and reporting, that there are many factors that make schools good schools. I challenge them to think about what they consider to be the purpose of education. I’m not against exams – I quite enjoy them and think they do have some role. But to value and promote this view of educational purpose so widely, so publically and indeed in policy, is folly. Education is much more than an Attainment 8 score, let alone the unaccountable pass mark in the 11-plus.

I know all the ‘worst’ schools mentioned in the report and they are not full of the worst pupils, or the worst teachers, nor do they have the worst parents. It is shameful to suggest, by the nature of the headline and the policy of allowing testing children at the age of 10, that this is the case. Likewise, it is ridiculous to suggest that the ‘best’ schools are truly the best. All of those schools are populated with hard working (and lazy) pupils, great (and not so great) teachers and wonderfully supportive (and not so supportive) parents. We are in danger of creating an education system that is no longer educational and as such no longer fit to play the vital role of educating young people to become active democratic citizens.

Sadly, the Kent report has failed in the fundamental journalistic function to question those in power, only serving to perpetuate a damaging and hateful obsession: seeing the worth of young people only in the metric of a test score. It seems as though the government is intent on delivering an education that is measurable instead of memorable.

Dr Alan Bainbridge is the Joint Coordinator of the Kent Education Network and member of Comprehensive Future’s Selection Working Party. He currently lectures in higher education having previously taught in Secondary Schools for 20 years. He is writing this article in a personal capacity.