Alan Parker’s proposals for new School Admissions Authorities and reforms to the 14-19 curriculum are logical and coherent. They provide a non-controversial approach to the phasing out of selection at 11. They would reduce many of the glaring inequalities in our secondary school system.

They build on a series of recommendations for 14-19 reform over a quarter of a century including contributions from the IPPR and the Labour Party (fully developed by the Tomlinson report) and, more recently, strongly advocated by Kenneth Baker.

These proposals would probably require at least a decade (i.e. probably at least two parliaments) for full implementation. This assumes a degree of continuing political consensus that might be difficult to sustain given the irrational ferocity of some of the defenders of selective education.

However, there is another way to build a solid and enduring public and political consensus in favour of non-selective secondary schools within the lifetime of one parliament which would be entirely compatible with a longer term programme of curriculum reform.

The 2018 Comprehensive Future Manifesto calls on all political parties to commit, unequivocally, to outlawing the use of 11-plus tests by a specified date. It would be entirely feasible for such legislation to be passed within the first year of a parliament, with implementation two years later.

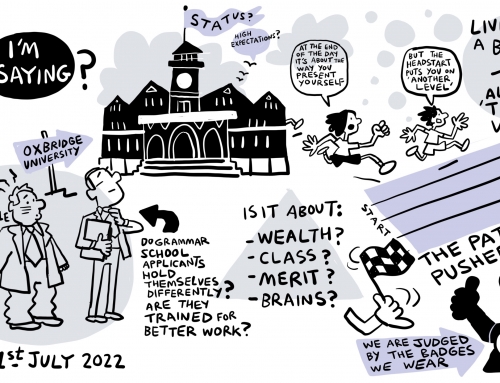

The growing public discontent, even amongst supporters of selection, with the arbitrary, secretive, expensive and unfair nature of 11-plus testing, should help to minimise political opposition to the first stage of this process.

The future admissions policies of all affected schools would then be required to comply with the guidance contained within a revised National Admissions Code . Compliance would be ensured by the proposed new Admissions Authorities.

Where the ending of testing at 11 is considered to require major change to the structure of the local system of schools, an extensive public consultation would be conducted by the relevant local, or regional, authority.

The views of parents in all publicly funded schools should be taken into account and a range of options for future school structures should be presented and explained impartially. The final choice of preferred option would need to be determined democratically, but there could be different mechanisms permissible (local/regional authority, parental referendum, ballot of school governing bodies etc).

In the fifteen wholly selective local authorities, this process should lead to a well informed local debate involving very large numbers of parents and teachers. The new arrangements to be put in place to replace the use of testing at 11 would almost certainly require considerable new capital investment

With regard to the remaining free standing selective schools, the decision on future school arrangements is likely to be much more straightforward but may still require some capital investment.

Depending on local circumstances, it is possible to envisage a wide variety of structural solutions being proposed, including 11-16 schools plus sixth form colleges and/or 14-18 schools. Some areas may consider a return to middle schools; others an experiment with all through schools. Whilst for some, simply maintaining the existing 11-18 system may seem preferable.

Whichever model were adopted, it would gradually become clear that our secondary school system is best organised in two phases (i.e. Lower/Upper Secondary or Junior/Senior High) as is common in most OECD countries.

The crucial point is that local decisions on future school structures are more likely to be taken on the basis of evidence of what works in the interests of all children, and less on obsolete notions of fixed intelligence or cynical political calculations in marginal constituencies.

Disaggregating the question of the 11-plus test from the question of the future structure of a non-selective system is the key to minimising political objections and maximising public support.

Securing a mandate for the abolition of the test from the nation as a whole in a general election, whilst making the future structure of schools a matter for local determination, would ensure that the debate on alternative structures would be more focussed and better informed. This would also allow for a considerable degree of variation to reflect local circumstances.

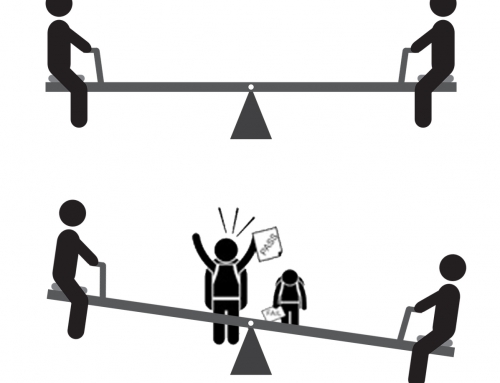

Parents’ capacity to choose a school, rather than a school’s power to select its pupils, would be maximised. However, the significance of the choice at 11 would actually be reduced as gross inequalities between schools were gradually eliminated. Young people would gain more control over their studies, and their lives, as the key decision would no longer be which school is prepared to accept them at 11 but which specialisms they choose to follow from 14.

England would finally follow the approach adopted many years ago by those countries that best combine the highest levels of achievement with the lowest levels of inequality.

David Chaytor was the first Chair of Comprehensive Future, a former member of the House of Commons Education Select Committee, Chair of a Local Education Authority, and, previously, Head of Continuing Education in one of England’s largest colleges. He is writing this article in a personal capacity.