By Torrin Wilkins

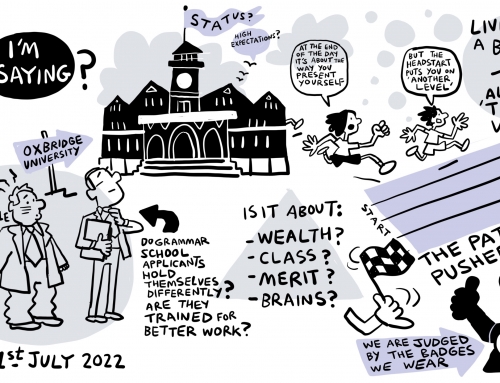

The other day I interviewed an aspiring teacher on the UK’s complex and often disjointed education system as part of the podcast run by the Centre think tank. During this conversation, one topic came up that we continued to discuss after we had recorded the episode, grammar schools.

The other day I interviewed an aspiring teacher on the UK’s complex and often disjointed education system as part of the podcast run by the Centre think tank. During this conversation, one topic came up that we continued to discuss after we had recorded the episode, grammar schools.

Running a think tank, you end up looking at all areas of policy; whether it’s business regulations, the health service or indeed education. Yet grammar schools are perhaps one of my main concerns because it’s not often that you see a system as flawed as this one.

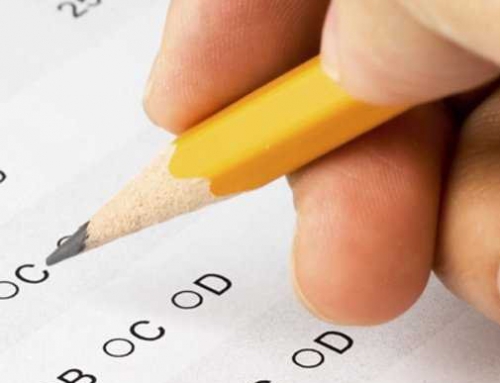

The first issue is with the 11-plus test, a test with issues even as a standalone idea. The test is essentially a memory test rather than a test of intelligence meaning many intellent students are told they aren’t because they don’t have a good enough memory. This is an issue I have struggled with myself; I head a think tank, yet I probably couldn’t get into a grammar school. Something is incredibly wrong with the system when that’s the case. Another point is that with automation, remembering things simply isn’t as useful anymore. It’s thinking about things that matters, not just having a good memory.

As part of writing this article I looked at 11-plus test papers to give me an idea of what children had to pass, and it genuinely worries me. Guessing the pattern or the missing letter of a word is not a good measure of someone’s full academic intelligence. Whether it’s handing the test to people going into teaching, doing it myself or giving it to my other friends at university, there was one clear consensus, this isn’t a good way to test intelligence.

Another issue that I would also face is being a summer born baby. It was often at parents evening where other parents would wonder if I had special needs because my grades were low, it wasn’t. It was down to the fact that I was almost one year younger than everyone else. The test tries to make up for this with a few extra points but it’s nowhere near enough to offset the disadvantage summer born babies are at in these exams. They haven’t had enough time to develop yet and catch up with the rest of their class.

I was also slow to develop academically, and the fact is everyone develops at a different rate. As a result, testing at the age of 11 means students that will be brilliant academically are told they aren’t.

The final issue with the test is that it helps to entrench wealth inequality as use of private tutors means that no matter how much preparation schools do for the test, the 11-plus is skewed in favour of those from wealthier families.

Whilst some propose using other methods such as recommendations from the teacher and scrapping the 11-plus, unfairness will still be a problem. Summer born babies, slow academic developers and those without personal tutoring will always be disadvantaged in a selective school system. Teacher recommendations would end up favouring the students a teacher likes best, even if this was only through unconscious bias. No matter what system you use, splitting students at the age of 11 doesn’t work, children of this age are not old enough to decide whether they are ‘academic’ or not, let alone to be forced to prove it by passing a test.

This is also an argument about freedom of choice, with students in areas with grammar schools being forced to prove whether they are ‘academic types’ or not. We sometimes forget that if we want to get a student to do well in any area, giving them the choice to do what they want to do will help them to succeed in the long term. We want people who love what they are doing because this means they will have the drive to learn, rather than being told which route to go down at such a young age.

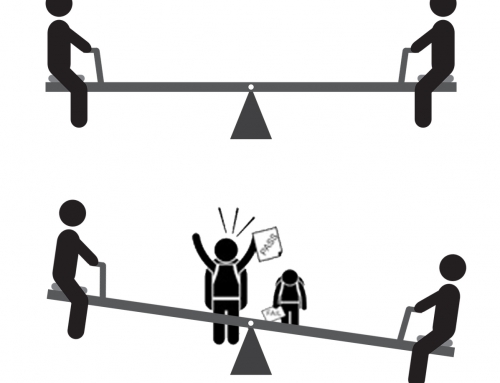

One of the main issues with selective education was expressed by Stephen Gorard, Professor of Education at the University of Durham, “There is repeated evidence that any appearance of advantage for those attending selective schools is outweighed by the disadvantage for those who do not”. This means the system takes students who are better at the 11-plus and then gives them an advantage, whilst taking students who perform less well at school and disadvantaging them further. The person who needs more help somehow gets less help in this system.

When put like this, the response I have often had is that people agree with the arguments but don’t see how then can argue against grammar schools when they or their child is in one. If you continue to live in the area and your child doesn’t get in, they will be on the opposite end of the system in a school that may well be less suited to fulfilling their educational needs.

In the end there is little else that can be done other than to open grammar schools to all students, regardless of ability. This is one of the reasons I support Comprehensive Future’s reports on how to phase out selective schools and integrate them into the wider education system. I have come far in the education system and there are a few teachers I will always be grateful for, getting me to where I am now, yet I feel like there is no point in struggling in a system if I don’t try to change the system.

Torrin Wilkins is an Aberystwyth University politics student and Director of the Centre think tank and pressure group, supporting stronger public services, free markets & free trade. He is writing this article in a personal capacity.

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and are not necessarily Comprehensive Future policy.