I once stood in a station queue the day before the school term started, as parents and children sorted out travel passes.

I once stood in a station queue the day before the school term started, as parents and children sorted out travel passes.

“I need a season ticket for her to go to grammar school,” the first mum said.

“She’s starting grammar school tomorrow,” said the next mum. “Do I need a photocard?”

There is something about grammar schools that makes people use two words where one would do. It’s not a conscious thing but it happens.

My local paper does this too. ‘Grammar school boy performs CPR’ says the headline. A news story says, ‘grammar school pupil drugged and robbed.’ Are we supposed to care more about the victim of a crime if we think she’s smart?

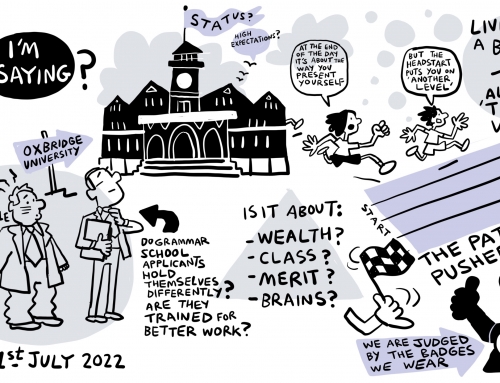

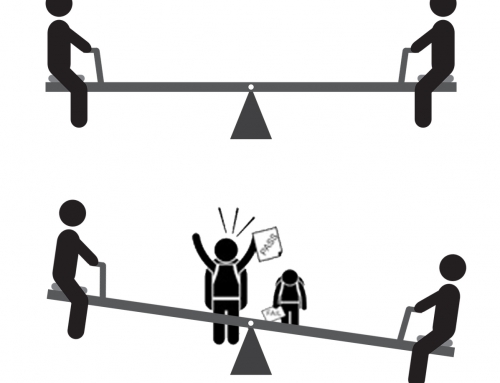

‘Grammar school’ is shorthand for “brightest and best,” divided secondary eduction means winners and ‘the rest’. We have an attention-grabbing label of intelligence, and we have children walking Kent streets wearing uniforms suggesting low scores in a test. We would never create clothing labels for adults describing intelligence or less intelligent, what kind of mind contrived this as a plan for eleven-year-olds?

The people who attend grammar schools are members of the ‘top 30%’ club and they benefit from the status this confers. It’s a lot of weight for one short test to carry, but no one talks about that side of it. The members of this club get a nice label for their CV, go to universities, get great jobs, and many become councillors, MPs and policymakers. They gain the power to influence education, and what do they do? They know their world, they think, “We need more grammar schools.”

But what about the people who don’t go to grammar schools? What about their schools?

The DfE collect data for ‘non-selective schools in highly selective areas.’ Non-selective-schools-in-highly-selective-areas are not quite like comprehensive schools. The DfE counts them as a separate category of school because they’re different. Yet no one in a Kent station asks for a travel pass to get to a ‘non-selective-school-in-a-highly-selective-area.’ I’ve never seen a local newspaper headline say, ‘Non-selective-school-in-a-highly-selective area pupil saved life with CPR.’

Of course, we used to call these schools secondary moderns, but that phrase fell out of fashion. Selective councils used to call them high schools or upper schools, now they might say all ability school or comprehensive, but more likely it’s simply school, and the word academy muddles things even more.

If you don’t name something you can’t talk about it. So we don’t talk about the schools most children in grammar school areas attend, because there simply isn’t a word for it.

Do you see what I did there? I called it a grammar school area. The minority school for the winners defines the whole education system. The losers go to schools without a name, in a school system named after the only school we can talk about.

There are other problems with language in the selection debate. People say, “I passed my 11-plus.” The opposite of a pass in 11-plus areas is always, “You didn’t pass.” This verbal trickery is essential because no one ever wants to say “you failed.” That’s too powerful. It hurts, and remember these are ten-year-olds.

The phrase, “you didn’t pass” is our protection. The mums and dads, the teachers and testers, the people with power and responsibility are trying to reassure our trusting children that this isn’t wrong or cruel. It’s all just fine. They hide from the hurtful reality, and who can blame them?

Language has power. So how would it be if we used language that represents grammar schools more accurately?

Theresa May could give a speech and say, “I want to expand Exam Passer Schools because these schools get the best exam results.”

Damian Hinds could say, “I have a £200 million expansion fund for Test At Ten Schools, because I know parents love Test At Ten education.”

Sir Graham Brady could stand up in Parliament and say, “I represent Trafford which has many fantastic Pass You’re a Winner Schools and lots of great Fail You’re a Loser Schools.”

Of course this won’t happen, and instead it’s easy to simply say, “I went to a grammar school, I loved it. Let’s make some more great grammar schools.”

They might even say, “People love the grammar school system, we should listen to them.”

And if we listen we will hear people talking about grammar schools. They love this thing that is good for their sort, and their children, and all the people they know.

The problem is the rest have no words. The rest are quiet.

… They attend schools with no name, how can they talk about their education?

…They were given a failure label no one ever wants to reveal, why would they want to talk about that?

…If they criticise the schools for the “brightest and best” isn’t that ungrateful and ill-mannered?

….How can they question schools representing excellence and success? Who are they to challenge something so powerful?

They’re quiet down there, and shouldn’t we consider that silence. Isn’t it odd?

We make people feel stupid, we give them no words to describe how they are hurt, and we give all the advantages to someone else, and then… nothing?

When people with power hurt someone who feels helpless we call this bullying. When the grammar school winners press home their advantage isn’t this thoughtless bullying too? A selective school system shames and silences a majority, while the winners pocket £200 million of education funding and cheer.

I’d like Damian Hinds, our education secretary, to visit a Kent primary school on test results day. I’d like to hear him describe his plans with simple words to a ten-year-old.

I’d like him to meet a girl who “didn’t pass” and explain his selective school expansion plans to her. I’d like him to look her in the eye and explain why he likes the 11-plus and grammar schools. Maybe he could ask her how it feels to give up dreams of a bright school future, and wear a uniform that marks her as different from her friends?

The people who fail and lose out in a selective school system are easy to ignore, they have no voice, but they must never be forgotten.

Joanne Bartley is the Campaign Support Officer for Comprehensive Future. She is writing this in her personal capacity.

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and are not necessarily Comprehensive Future policy.