By Dr. Alan Bainbridge

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and not Comprehensive Future policy.

There is a charming tradition in the USA where in the run-up to Thanksgiving, one bird is chosen to be ‘pardoned’ by the President. I’m not sure quite what they are being pardoned for but the lucky bird is allowed to live out its natural days free from the fear of ending up on a dinner plate. The birds are given names and the whole hoo-ha is quite a celebration that cleverly detracts from attention the slaughter of tens of millions of less fortunate turkeys. This is not my metaphor but one I have shamelessly stolen from Arunduti Roy, and it serves to help us all take a deep intake of breath as we enter the frustrating world of how social mobility will be solved by opening more grammar schools.

I am becoming increasingly convinced that grammar schools are being offered a continued, or new, lease of life as some kind of distraction from the mess recent governments have been making of education policy. To push the metaphor further: one view of schooling is being promoted (we could argue ‘pardoned’ – if this decision is based on what research tells us about their impact), while all others are being left to wither and die.

The recent HEPI report on how grammar schools will enhance social mobility is a typical Thanksgiving turkey gesture. The public have already been exposed to headlines confirming – because this is how they are presented – that grammar schools are to be saved amid a dystopian nightmare of deregulated academies and free schools, voluntary aided and maintained schools, community schools and the list goes on. The grammar school is lauded, held high and saved. If this sounds slightly fanciful, I will just briefly take you on a detour to the nine secondary schools all within a short drive from this keyboard. As austerity continues to bite school funding remains under pressure and between 2015-2020 the three grammar schools will experience no budget cuts, while the 6 secondary modern schools will lose £1,125,000. When that is taken into account alongside voluntary contributions, gifts and donations, state schooling is facing a crisis – but ‘Hey’, let’s all celebrate a handful of young people entering an elite university.

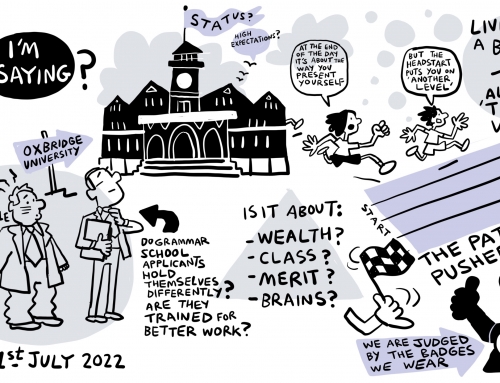

The latest turkey being offered up has come from the HEPI think tank from an author who makes the headline claim that all the previous research on the limited impact of grammar schools, are wrong. This clever fella has found out that everyone else has been looking at the wrong data and that grammar schools are actually very successful at enhancing social mobility, or getting a place at an Oxbridge university. It is not my intention to rehearse the litany of arguments against this research within this report – this has been covered far better by many more experienced colleagues.

Suffice to say a colleague and I marked the work as if it was a Year Three dissertation – and the inability to ground the work in the past literature, devise a suitable research question, justify the methodology using previous similar research, provide a rationale for the analysis and clearly explain their findings – leave this soundly in the lower 2:2, possibly 3rd classification. There was some acknowledgement of the amount of work carried out which saved the ignominy of having to re-submit.

The HEPI report is a shocker, and desperate back-peddling now informs us that it was only intended as a provocative thought piece. But just like the Brexit bus and claims to put multi-millions back into the NHS every week caught the public’s imagination, HEPI are now responsible for peddling the lie that saving grammar schools will serve the educational holy grail of social mobility … All while other schools and their educational purpose are desperately trying to stay alive.

There is something quite messy about education: one aspect is to do with what is its purpose, and second related to how do we find it if it ‘works’. The previous debate provides some insight to the second point, as finding out about cause and effect in education is remarkably complicated. While crafts have landed on Mars and tiny robots can now carry out micro-surgery the debate about the link between early educational attainment and how to get to an elite university continues to rage. As such, formal schooling is now embedded within a mishmash of ever-changing policy initiatives including different types of school to such an extent that it is difficult to argue that, at least in England, for the presence of anything resembling a school ‘system’.

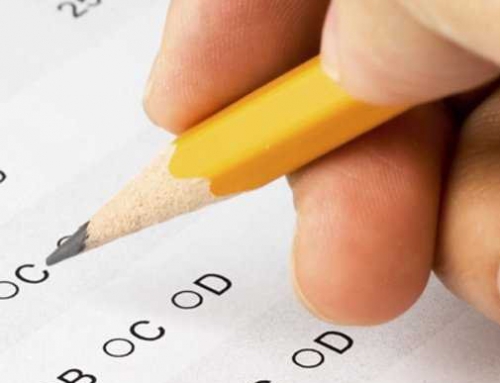

It appears as though the only substantive thinking about education is linked to maximizing and monitoring educational attainment. But the purpose of education is more than this. To think about purpose and what values underpin this brings us back to thinking about both the rationale and efficacy that underpins the idea to organize secondary education through the use of a short test taken at the age of 10. That this test is referred to as the 11-plus disguises the fact that some children were 9 a few weeks before sitting this test, most are 10 and a few are 11. What is more, is that many of those taking this test would have been ‘coached’ from the age of 8/9. Hence, the impact of the short 11-plus test on how school systems are organised can be perceived throughout most of the lifespan. Sticking with this test and its associated system of schooling assumes the acceptance of the following values.

The purpose of education in an 11-plus school system:

- Segregation of young people from the age of 10.

- Overemphasises the importance of testable knowledge.

- Encouragement of competition, rather than collaboration.

- Favours test scores over professional judgement.

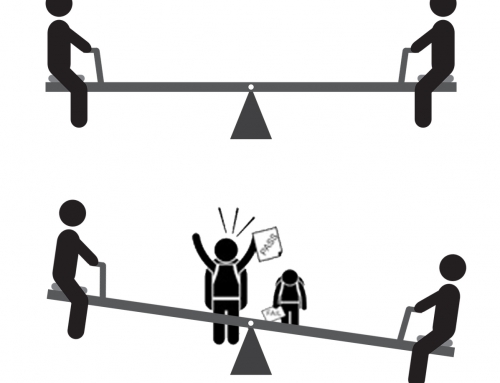

- Promotes both ‘upward’ and ‘downward’ social mobility.

- Social mobility is more important than social cohesion.

- Suggests education can solve societies problems.

Segregating children at 10 and reducing their future opportunities requires taking a stance that assumes ultimate trust in the accuracy and truth of the 11-plus test. Focusing on the test detracts attention away from an education that considers how we can work together, care for each other and the world we live in. Additionally, schools are seen to be in direct competition for pupils and financial resources, including voluntary contributions. There is an assumption that good democratic decisions and opportunities can emerge from a population who had dramatically different educational experiences. The focus on social mobility is always directed ‘upward’ and assumes a desire to throw off the shackles of lower social status: the possibility that this might not be desired, or that the opposite may also happen, seldom enters the debate. There is also the rather blinkered and hopeful assumption that schools are able to put right all the wrongs created by long-term political decisions making.

A way forward without having to kill turkeys.

The promotion of a system of schooling organized around the 11-plus is only possible if the destructive impact this has on all levels of education is hidden from view. Just as saving the Thanksgiving turkey distracts attention away from the mass slaughter of other turkeys, so to a tempting offer to save (increase) the number of grammar schools distracts from how this will impact the wider system of education.

I have said this before but it is always worth repeating – my complaint is not with grammar schools (or their accompanying secondary moderns) but the dubious values that support testing children at the age of 10. So how can we imagine an education where trivial acts to offer £50 million to save a turkey are not necessary? How can we imagine an education that sees social cohesion as more desirable than social mobility? Finally, how can we imagine an education not obsessed by segregation but one that values all individuals by providing genuine opportunities for choice?

I offer a few brief but far more morally acceptable ways forward:

- Provide comprehensive education organised by local education authorities from the early years to, at least 16.

- Promote informed educational choice at 16 and not segregation at 10.

- Focus on social cohesion and not social mobility – on collaboration, not competition.

- Look beyond education and consider the impact of housing, benefits, tax and ability to travel.

- Trust a well-educated education profession to make wise decisions.

Dr. Alan Bainbridge is the Joint Coordinator of the Kent Education Network and member of Comprehensive Future’s Steering Group. He currently lectures in higher education having previously taught in Secondary Schools for 20 years. He is writing this article in a personal capacity.