By Jo Bartley

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and not Comprehensive Future policy.

It’s secondary school open day season here in Kent. The majority of children are waiting for their 11-plus results, so there’s uncertainty about which schools to visit. Planning trips to either non-selective or selective schools only draws attention to the nervous wait for the test verdict.

It’s secondary school open day season here in Kent. The majority of children are waiting for their 11-plus results, so there’s uncertainty about which schools to visit. Planning trips to either non-selective or selective schools only draws attention to the nervous wait for the test verdict.

Soon an email will reveal the school deemed the ‘best fit’ for each child. Anyone with a score of 320 or more is “suitable for a grammar school” while a child with 319 points or less will be “suitable for high school.” Many children are borderline, but a line is drawn and that’s that.

I would like to see Kent County Council’s workings out for this process, their reasons for their chosen numbers and percentages, their checks to prove the accuracy of their 11-plus judgement. Or at least an honest acknowledgement that this isn’t actually real – children do not fit neatly into their two boxes. The council want this to be black and white, sheep and goats, smart and stupid, but who really believes in this daft, divisive, system?

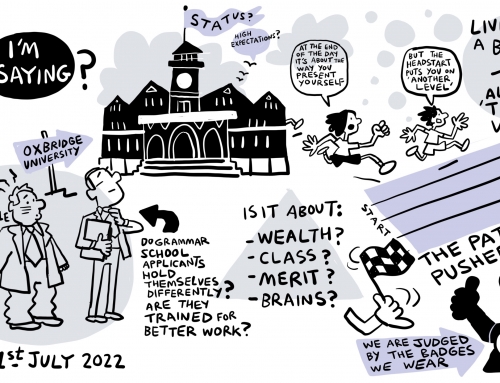

Grammar school fans, and a certain kind of Tory politician, will talk about the advantages of a ‘diverse’ grammar school system offering parent’s choice. Only I don’t know a single parent who enjoys the ‘choice’ offered by Kent’s system.

School choice in a selective area is more stressful than most places, but I suspect that this system is failing parents everywhere. Parents are all looking for the same prized things when they review their school options, things like:

Results and league table stats

These almost entirely reflect the proportion of smart hard-working pupils attending the school. Only no one talks about this. The Telegraph even publishes league table results for “the best” grammar schools, unsurprisingly the top places are taken by the schools that select out the most pupils. This isn’t offering a good education, it’s refusing education to those who need it.

The reputation of the school

Was it founded in 1527 with the benefit of a beautiful old building? Has it got fresh paint and the ‘wow factor’ of being some fancy new Free School? Or is it an unfortunate place that’s educated unwanted pupils for decades and can’t shake off a dreary image? Reputation is mostly gossip, tradition and marketing, but we all get sucked into caring about this.

Ofsted ratings

Ofsted is like traffic lights for school choice. ‘Outstanding’ means go, go, go – the school is everybody’s first choice and always oversubscribed. ‘Good’ is amber – you put it as second choice and don’t mind if you get a place. Requires improvement means STOP – you either can’t read or don’t have internet. I’m not sure who thought this system worked or helped parents in any way.

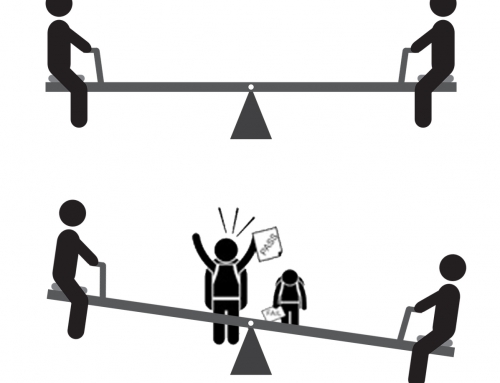

These three factors are assessed and then the schools line up in a local hierarchy. Some schools will have many advantages, the more exclusive and selective they are the more appeal they have, because it’s human nature to want the rare prize, not something anyone can achieve. This means that schools in Kent sort themselves into three tiers, grammar schools at the top, faith schools in second place, and the schools that take the remaining pupils are bottom of the pile. Then the parents sort themselves into a hierarchy to claim the ‘best’ places. The wealthy and the smart win the “best” schools and the most options.

A lucky family with good genes and money, who go to church, will have a choice of grammar schools, faith schools and the best non-selectives. A typical well-to-do family might play the card of faith or an 11-plus pass, and have a reasonable number of schools to consider. An unlucky parent, without any faith, who didn’t bother with the 11-plus, will only have a few options of the nearby undersubscribed schools. A school bus pass in Kent costs £290 a year, so poorer families might well choose the only school within walking distance.

I don’t think our politicians consider that our school choice system rarely even makes parents happy. We all know that each school is a complex mix of factors, the ‘lucky’ parents with many choices might pick an ‘Outstanding’ rated boys grammar school, obliged to choose it based on its results and reputation, but worrying about it being single sex. The family who win a faith school place will worry that a grammar school is more academic, regretting that they didn’t have that ‘choice’. And what is a ‘good school’ anyway? Creating all these options is more likely to leave parents confused and stressed rather than loving the diversity of the local school scene.

Imagine if everyone had a simple choice of just two or three local schools, all perceived as equal, but different in subtle ways?

I understand the idea of creating more choice, a competitive schools ‘market’ is supposed to encourage diversity, with good schools growing and bad schools closing – but this is playing games with our children’s lives. No one would stand for a market for our hospitals. If patients were offered a choice of bad or good hospitals with league tables for death rates we’d be horrified. No one would think the losers who ended up with a bad “choice” of hospital deserve to suffer for some overall system good. So why do we think this works in education?

We label and rank schools to help parents with their “choice,” but the labels are flawed and the admission rules create unequal choice. Our school hierarchy certainly doesn’t help pupils. How does any child work hard and thrive when we’re telling them to doubt the quality of their education? How can it be right for any child to attend a bottom of the pecking order school, while the world says the school up the road is better and its children smarter?

Parents worry, care, weigh up pros and cons, and try to make the ‘right’ school decision. It’s completely natural to want the shining school at the top of the hierarchy. It takes a brave parent in Kent, to step away from the 11-plus game, ignore the evil pushers of league tables, Ofsted ‘Outstandings’ and schools for the brightest and best. To step away from all this is to risk something as precious as your own child’s education.

But if we can step away we see that every school is a mix of good and bad, and that a great teacher or a bunch of friends matter more than anything showing up on a web page, or an open day.

We should end the winners and losers schools competition with all its stressful options. We should focus on creating equal, excellent, local schools. Why not give everyone the three closest schools as choices, with open access and no schools allowed to choose their own pupils? If every child can attend a good local school, with no tests, no fuss, and no marketing hype, there would be many more happy parents, and many more children glad to start a new school with local friends.

Joanne Bartley is the joint co-ordinator of the Kent Education Network and Campaign Support Officer for Comprehensive Future. She is writing this in her personal capacity.