By Dimitri Coryton

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and not Comprehensive Future policy.

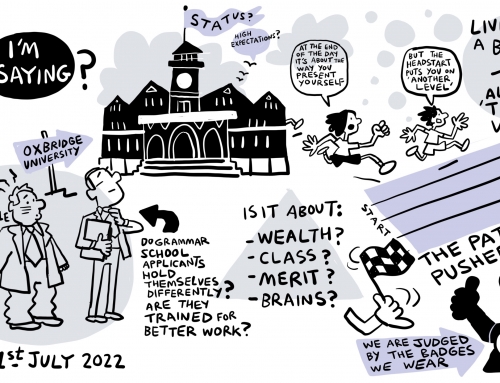

The Government’s response to the consultation document Schools That Work for Everyone had been a long time coming, and not just because around 7,000 people and organisations had responded to it. It was a pretty unimpressive document, a rag-tag of unconnected proposals affecting universities, faith schools, independent schools and grammar schools – as well as the secondary moderns that would have been further disadvantaged by its proposals, although Ministers seemed strangely reluctant to dwell on these schools although a majority of young people in selective areas go to them. Indeed, the name of the document should more accurately have been Schools That Don’t Work for Everyone.

The Government’s response to the consultation document Schools That Work for Everyone had been a long time coming, and not just because around 7,000 people and organisations had responded to it. It was a pretty unimpressive document, a rag-tag of unconnected proposals affecting universities, faith schools, independent schools and grammar schools – as well as the secondary moderns that would have been further disadvantaged by its proposals, although Ministers seemed strangely reluctant to dwell on these schools although a majority of young people in selective areas go to them. Indeed, the name of the document should more accurately have been Schools That Don’t Work for Everyone.

If the original consultation was a shoddy enough document then the consultation outcome published on a Friday (generally considered a good day to bury bad news as Saturday’s newspapers are not read as widely as those published on weekdays and have less hard news in them) was an even thinner and less impressive creation. This was largely because in the intervening period Mrs May had thrown away the Conservative parliamentary majority with her hopeless general election campaign last year.

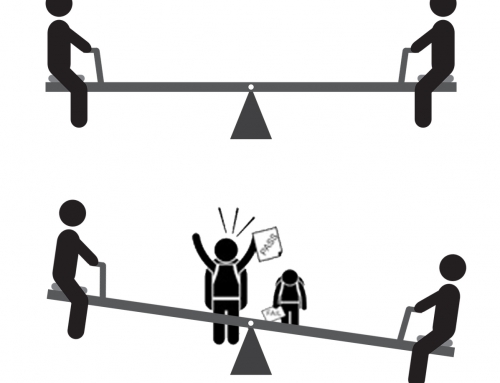

Part of the reason for her catastrophic decline in the polls, from a 24 per cent lead to a minority government, was her ill considered plan to expand the number of grammar schools into areas that had long ago abandoned them. This included a large number of Tory shire counties where voters were quite happy with their comprehensive schools that are delivering ever higher standards of education. Just how far we have come is illustrated by this figure. The number of people that our largely comprehensive system now sends to university is twice the number who in the early 1980s obtained five GCE O-levels. Those who now go on to higher education are roughly twice the number who, in a selective area, go to grammar school.

There are some grammar schools who now have more people in their sixth form who failed the 11-plus, went to a secondary modern and then transferred into the grammar school at 16 for A-levels than who passed the 11-plus and had all their secondary education at the grammar school.

So why on earth does Mrs May want to put the clock back and return to a system that, far from providing a ladder of opportunity for those from deprived backgrounds, as she claims, discriminates against them? After 70 years grammar schools still admit far fewer people from poor backgrounds, as measured by free school meals, than they should and far more from private schools. This should not surprise us, as it is what the post 1944 grammar schools were designed to do. They were designed to be a way of subsidising the education of middle-class children, while all but a few working class children would be catered for in secondary moderns. How do we know this? Because Clement Attlee’s post war Labour government helpfully wrote to all local education authorities to remind them that secondary moderns were for the working class.

Twenty years later and not much had changed. In our Times Were When series of reports from our archives we reproduce an article from 1963. The chairman of Birmingham Education Committee reported how pass rates for grammar school depended on where you came from. They ranged from 11 per cent in the poorest inner-city areas to 53 per cent in the middle-class suburbs. The more prestigious direct grant grammar school took a third of its intake from a small number of private schools which crammed for the 11-plus. The grammar schools enjoyed 80% more funding that the secondary moderns and a virtual

monopoly on university entrance.

In most of Britain that system has long been swept away. In one study after another, from Britain and, through the OECD, abroad, comprehensive schools do better for children than a selective system. As research published just a couple of months ago showed, once you allow for social factors, grammar schools don’t even perform better for the brightest. The Government’s claim, in a press release, that those from poor backgrounds do better in grammar schools is also false. Of course, very few such children get into grammars in the first place. The only time most poor children get to see a grammar school is when they walk past one on their way to their secondary modern. While the proposals announced on Friday are limited and not new, they are still hopelessly mistaken.

This comment piece by Dimitri Coryton first appeared in Education Journal, it is reproduced with the kind permission of the author.