By David Chaytor

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and not Comprehensive Future policy.

The 1998 Education (Grammar School Ballots) Regulations fixed the arcane rules for parental ballots on the future of selection by ability in England’s 164 (now 163) wholly selective secondary schools.

The 1998 Education (Grammar School Ballots) Regulations fixed the arcane rules for parental ballots on the future of selection by ability in England’s 164 (now 163) wholly selective secondary schools.

Three forms of permitted ballot were created with two different and carefully engineered electorates. 20% of eligible parents’ signatures, with full verified names and addresses, were required to trigger the ballot. Individual schools, and local authorities, were banned from campaigning. Unsurprisingly, only one ballot actually took place.

However, it would be a mistake to dismiss these regulations as an obsolete exercise in devious administrative ingenuity solely designed to prevent change.

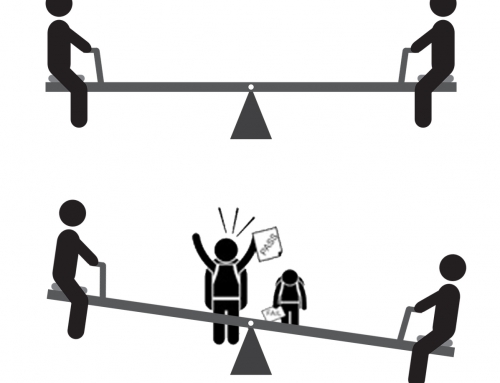

Revisiting the 1998 regulations could provide a popular means of resolving one of English education’s biggest problems—the vast inequalities, and the scale of social and cultural segregation, between our secondary schools.

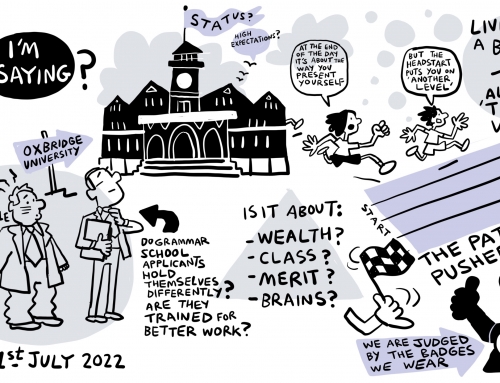

‘The thought that the Grammar School Ballot Regulations were designed to preserve the status quo is inescapable’ was the conclusion of Kent’s anti-selection campaigners in their evidence to the 2005 House of Commons Select Committee Report. Fortunately, it wouldn’t require much effort to redesign the regulations to make preserving the status quo almost impossible.

In any referendum, four issues are crucial; the question, the electorate, the trigger mechanism, and the rules for campaigning. The 1998 Regulations asked the wrong question of a skewed electorate with almost impossible hurdles for triggering a ballot. Key interest groups were prevented from participating in any campaigning.

It should not be difficult to write a new set of ‘Education (Comprehensive Reform Ballot) Regulations’ designed to generate a serious and well-informed debate, leading to a local referendum, on the future structure of secondary schools in each of the 26 local authorities with wholly selective schools.

Out would go the standard ballot question on ending selective tests with no description or explanation of an alternative. Out would go the extraordinarily high numbers of signatures required to trigger a ballot—and the almost impossible deadlines for verifying signatures. Out would go the gerrymandering of the electorate by the use of carefully chosen feeder schools. And out would go the ban on local authorities actively campaigning for an alternative, as their responsibility would be to propose the alternatives.

It would be preferable, though not strictly necessary, for Government to have announced in advance a date for the end of 11-plus style entry tests through a revised Schools Admissions Code and associated legislation. In that case, the CSR ballot would offer a number of alternative forms of school organisation following the ending of the 11 plus.

However, the 11-plus question could still be the first question on the ballot paper, followed by one or more of the alternatives. These would be developed by the relevant local authority, or grouping of local authorities, in consultation with all schools, academy chains and religious authorities directly concerned.

In respect of a trigger mechanism for the ballot, this could be at the discretion of the local authority based on requests from a minimum number of relevant school governing bodies. If there were no call for any reorganisation, there would be no ballot. It should also be possible for schools in adjacent areas, and other local authorities in which partial and covert selection has a significantly damaging effect, to initiate a similar local referendum process.

In terms of the electorate, the maximum participation of those with the most direct interest in, and experience of, of local schools should be the guiding principle. This would logically result in all parents, teachers and possibly support staff at local state primary and secondary schools being eligible to vote.

As to the rules for campaigning, given the ballot offers a choice between clearly explained alternatives, exactly the same principles applicable to other local and national elections and referenda should be adopted with particularly careful attention paid to limits on spending.

The use of a local referendum of this kind would have a number of advantages.

It would respond to the concerns of those who genuinely believe that selective admissions policies should be determined locally by providing the opportunity to do exactly that.

It would respond to the concerns of those who claim to be opposed to selection at 11, but nervous about the local political consequences of changing the nature of wholly selective schools. It would be made clear that crucial alternative roles for all these schools would be established in a new system (not excluding selection, or student choice, at 14).

It would re-engage parents and teachers in a deeply relevant community discussion that goes beyond the usual obsession with testing and league tables. It would give them a voice in not only shaping their children’s individual futures but also the future of the wider community.

It would ensure a debate in which assumptions are challenged by evidence and prejudices by reasoned argument. It could even start a long overdue process by which local democracy starts to take back control from the top down privatisers and centralisers.

Above all, Comprehensive Reform Ballots would ensure that, for the first time in many years, decisions on the future of secondary schools are based on the aspirations of all parents, and the needs of all children, not just a few.

This article is by David Chaytor, the first Chair of Comprehensive Future, a former member of the House of Commons Education Select Committee, Chair of a Local Education Authority, and, previously, Head of Continuing Education in one of England’s largest colleges. He is writing this article in a personal capacity.