By David Chaytor

2020 will mark the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of ‘Half Way There’, the outstanding report by Caroline Benn and Brian Simon of progress towards a national system of comprehensive schools.

2020 will mark the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of ‘Half Way There’, the outstanding report by Caroline Benn and Brian Simon of progress towards a national system of comprehensive schools.

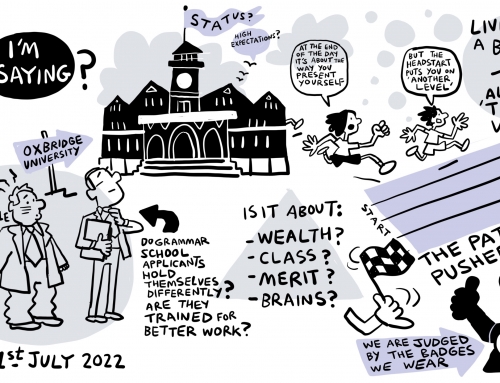

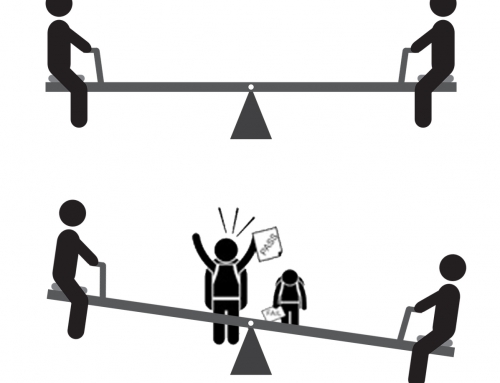

In 1964, 1966, and 1974 (twice) the Labour Party under Harold Wilson won two successive general elections with a commitment to ending selection by ability as a criterion for entry to state secondary schools. And yet, in England today, selection by ability, overt and covert, is still endemic. It is directly responsible for our intensely hierarchical system of state schooling and, therefore, our intensely hierarchical, deeply divided and increasingly unequal society.

Since 1974, no British Government has committed to completing the comprehensive reforms initiated by the Wilson Government with the celebrated Circulars 10/65 and 10/66. Successive Labour and Tory governments have not merely endorsed, but actively encouraged, selective admissions policies. The current Conservative Government has laid the foundations for a major expansion of selective schools.

So with another general election highly likely within the next few months, what are the prospects for reform of admissions policies in England’s secondary schools? We know the DUP, UKIP, Conservative Party and Brexit Party views on selection at 11. We know the SNP, Plaid Cymru, Liberal Democrats and the Green Party views on selection. But what of Her Majesty’s Official Opposition?

Jeremy Corbyn is the only Labour Party leader since Harold Wilson to have actually voted (as a backbencher) to end selection at 11. He is the only Labour Party leader ever to have a proposed a National Education Service and an end to the VAT exemption on private school fees. He is the only Labour Party leader to have proposed outlawing national academic tests at the age of 10.

Unfortunately, this last commitment only applies to the Key Stage 2 SATS used to measure achievement in primary schools (opposed by 97% of primary schoolteachers in a recent poll). Labour still supports the use of existing 11-plus tests, also taken in Year 6, as a means of entry to secondary schools.

Is this an ingenious, if slightly surreal, compromise halfway down the road to Labour shifting its wider policy on selection? Or not? Is Jeremy Corbyn still trapped by the influence of close allies, in the Shadow Cabinet and on the Corridor, who strongly support selection in principle, in practice or both?

The recent Labour policy shift on Brexit is highly relevant to policy on academic selection. If pressure from Labour Party members, and affiliated trade unions, can be deployed to override the advice of some of Jeremy Corbyn’s closest advisers and allies on Brexit, a precedent is set for pressure for party members and trade unions to prevail over academic selection. If they choose to do so.

However, this will only happen if supporters of a fully comprehensive system recognize, and respond effectively, to the arguments of those who defend the status quo, both within the Labour Party and in the wider electorate.

The harsh reality is that supporters of comprehensive schools (including teachers, parents, academics and politicians) have failed consistently over many years to win the argument against academic selection at 11.

Appeals to parental good nature, calls for social solidarity and social cohesion, detailed statistical analysis, exposure of industrial scale coaching, sympathy for children branded as failures, growing concerns about children’s mental health: as yet, none of these have succeeded in securing political change.

The problem is quite simple; the traditional pro-comprehensive case has been defined as a primarily political issue. Are you for or against selection? Progressives this way; conservatives that way. In a country not yet inevitably emerging from forty years of neo-Liberalism, this was never going to be a winning strategy.

So the arguments for ending academic selection at 11 have to be reframed as entirely educational and centred on a number of practical questions:

What is the purpose of selection? What is the right age for selection? What are the criteria? Who selects? What changes to school structures are needed? What is a reasonable process and timescale? What are the social and economic costs?

Once any form of selection is designed to improve every child’s opportunity to achieve, and not just to preserve traditional privileges, everything changes. The focus shifts from the institution to the curriculum. The earliest possible age of selection then becomes the point at which students already make choices i.e. KS4 when pupils choose GCSE. High stakes external tests can then be replaced by student choice informed by previous achievements.

Further questions should follow from a debate framed in this way. Exactly what is the purpose of GCSE? Are the terms ‘academic and vocational’ remotely useful any more? What on earth is happening with ‘T’ levels? What changes in school organisation would be needed in a fully comprehensive system? How do we ensure that selection by ability is not simply replaced by selection by house price? What can we learn from the world’s most successful secondary school systems?

So, back to Jeremy Corbyn. It may be that the next Labour Party Manifesto has already been written and includes an end to 11-plus testing and new policies on covert selection. It might also include a radical overhaul of the national curriculum, leading to some form of baccalaureate system. Or maybe not.

What is more likely is that it will take overwhelming pressure from the Labour membership and trade unions, and specifically the teaching profession, to break the logjam. To achieve this, new and practical solutions to the implementation of ending selection at 11 will be needed.

Corbyn has clearly thought seriously about the use of the Wilson/Benn compromise of a referendum to solve his current Brexit dilemma. He could usefully reflect on the fact that Wilson and Benn’s support for an equal chance for every child, by ending academic selection at 11, helped Labour win four general elections in ten years.

Half way there? It’s too early to say.

David Chaytor was the first Chair of Comprehensive Future, a former member of the House of Commons Education Select Committee, Chair of a Local Education Authority, and, previously, Head of Continuing Education in one of England’s largest colleges. He is writing this article in a personal capacity.

Our Future Thoughts series of articles are opinion pieces designed to provoke debate, they represent the views of the author and not Comprehensive Future policy.